Isabella Holland

Introduction

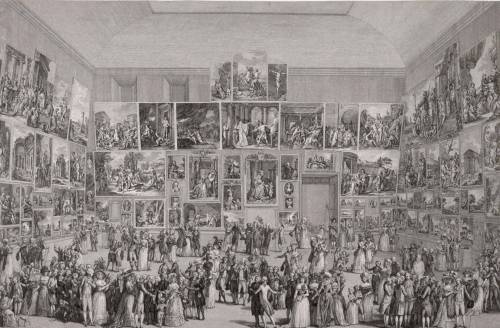

At their peak, these juried expositions swelled with thousands of artworks hung floor to ceiling in a testament to the creative productivity of artists working in each country.

Motivated to advance the fine arts in France and Great Britain, Royal Academies of Art based in Paris and London staged annual public exhibitions. Inaugurated in 1667 and 1769 respectively, the events, now known as the Salon and Summer Exhibition, played pivotal roles in introducing contemporary art to the masses.

At their peak, these juried expositions swelled with thousands of artworks hung floor to ceiling as a testament to the creative productivity of artists working in each country. Many artworks that are now part of the collections of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco originally hung in these massive displays. Rooted in these historical examples, Floor to Ceiling explores the Salon, Summer Exhibition, and the institutions that produced them.

The French Salon originated out of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), instituted in 1648 under Anne of Austria, the regent for her son, King Louis XIV. Comprising a body of painters and sculptors exclusively patronized by the monarch, the French Royal Academy promoted art-making in France through its teaching and exhibition programs. Elected artists, called Academicians, governed the institution and held the sole privilege of exhibiting at the Salon at its inception. Outlasting nine political regimes, the Salon drew its last breath in 1880.

Likely as a response to the French Salon, the British Royal Academy of Arts quickly launched the Summer Exhibition following its formation in 1768. Founded by a consortium of painters, sculptors, and architects and backed by King George III, the British Royal Academy emerged as the foremost private art institution in Great Britain. The Summer Exhibition, which continues to this day, employed an open call for submissions not unlike that of The de Young Open. This setup enabled both Academicians and independent artists to exhibit, with the ultimate selections made by the former.

Joseph Wright of Derby, elected into the British Royal Academy in 1784, presented The Dead Soldier at the Summer Exhibition of 1789. The painting was extremely well received, inspiring the artist to make this smaller copy of the painting.

The soldier’s vibrant red coat calls to mind the contemporary garb of the British military.

The Dead Soldier brings the consequences of Britain’s military actions around the world back to London. Exhibitions showcased art imbued with moralizing messages to impart to the public.

The Salon and Summer Exhibition established definitions for what French and British art was, and could be, for their art-loving audiences. Dense hangs shaped a collective glory for the achievements of each country’s artists, and inspired local pride, as the exhibitions primarily reached artists and visitors from Paris and London (not unlike The de Young Open and the Bay Area art community). Academies that sponsored the Salon and Summer Exhibition played powerful roles in curating hangs that privileged certain artists, and artworks, over others.

One of the most pressing issues faced in the discipline of European art history is resurfacing the stories of women artists.

In the eighteenth century, Salons and Summer Exhibitions provided women artists with a rare public opportunity—on restricted terms—to have their artistic output to be recognized. The courtesy to exhibit at the French Salon was extended to the four women artists who were stipulated to be in the French Academy at any given time, the only privilege equally shared with male cohorts.

At the British Royal Academy’s founding in 1768, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser were the only two women among its thirty-six originating Academicians (the next woman would not be elected until 1936). While both took part in Summer Exhibitions (alongside a few independent women artists), they were excluded from selection and hanging committees responsible for curating the exhibitions.

Tracing the careers of Anne Vallayer-Coster and Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun at the French Salon, two artists represented in the collections of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, we see the limits women faced at public exhibitions.

Anne Vallayer-Coster gained admittance into the French Academy in 1770 as a still-life specialist and presented an astounding eleven paintings at her 1771 Salon debut. At successive Salons, which she participated in until 1817, Vallayer-Coster continued to average this impressive number. Her tabletop compositions, lauded by Salon reviewers for their technical dexterity, attracted the notice of esteemed patrons like Queen Marie Antoinnette.

If all new members of the Royal Academy made a showing like Mademoiselle Vallayer’s, and sustained the same high level of quality, the Salon would look very different!Denis Diderot, 1771, Salon review

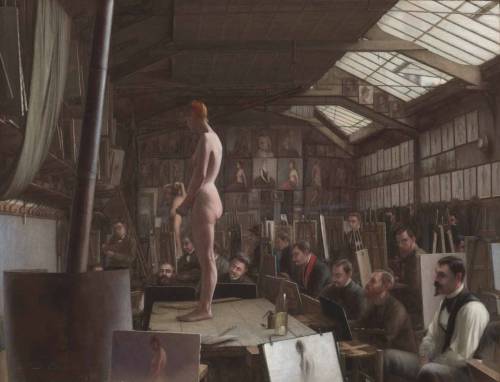

In Salon hangs that pitted artworks against each other, distinguishing oneself within the crowd was a feat. Again, this style of hang and the accompanying ranking system reiterated the disadvantages women artists faced. Barred from the life-drawing classes offered at the French Academy, women artists were denied access to studying the male models for grand history paintings (the British Royal Academy also barred female artists from classes employing male models).

Women artists such as Vallayer-Coster turned to subjects readily available to them in their daily lives, which tended to rank lower on the subject hierarchy. Although history scenes executed by male artists overpowered the gallery walls, women’s works still captivated the public, even with their small scale.

Where then would Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun have sourced a nude model to paint for her Bacchante, presented at the 1785 Salon? While best known today as the preferred portraitist to Marie Antoinette, Vigée-Le Brun sought to be recognized as a history painter upon her admission to the French Academy in 1783.

Vigée-Le Brun’s bold use of a full-frontal nude in Bacchante demonstrates that women artists sought to engage with the most highly esteemed art forms of their time, despite being actively restricted from doing so. Although the French Academy would only accept her as a portraitist, a genre in which she nevertheless innovated, Vigée-Le Brun continued to engage with the tenets of history painting throughout her career.

Severe masters will always be astonished that a young woman of charm and delicate constitution could have conceived such a bold undertaking.Anonymous woman critic, in L’avis important d’une femme sur le Sallon de 1785 [A Woman’s Important Opinion on the Salon of 1785]

Today, it is difficult for art historians to track the legacies of women artists who were members of the Academies and presented their work at Salons and Summer Exhibitions, and who are now haphazardly represented in the collections of cultural institutions worldwide. One of the most pressing issues faced in the discipline of European art history is resurfacing the stories of women artists and critically examining how their careers adapted to institutional structures that did not support them based on their gender.

This work relies on centering primary sources and voices, like the quote above, taken from a female art critic, and showcasing that women artists and audiences were deeply concerned with the art of their era. Looking at the narratives sourced from Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s own collection, it is clear that women artists played influential roles in shaping and contributing to the identities of French and British art through public exhibitions—not the ancillary ones in which they are so often cast.

Dissatisfied with the lack of autonomy in controlling their careers, artists increasingly called for the modernization of each institution.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Salon and Summer Exhibition, as well as their organizers, contended with a political climate shaped by revolution. The French Revolution’s abolishment of the monarchy, and its institutions, which did not spare the French Academy, shifted oversight of the Salon (which remained!) to the new government. Following this radical shift, all artists were invited to submit works for consideration by the Salon, and it led to the development of a jury consisting of artists associated with the École Des Beaux-Arts (a revamped French Royal Academy), a system that was similarly employed at the Summer Exhibition.

As submissions and audience numbers exponentially increased, parallel to social movements that made leisure pursuits more widespread, Salons and Summer Exhibitions became primary venues for viewing art, instrumental in making or breaking an artist’s career.

The Salon of 1855, part of the larger Exposition Universelle (Universal Exposition), mounted a retrospective for Horace Vernet. A rare homage to an older artist and artworks, the exhibition included our collection painting Scene from the French Campaign of 1814, painted in 1826.

A heroic mother saves her family from invading forces during Napoleon I’s last effort to take control of France. The composition served as an exemplar of French patriotism.

The artwork’s presence demonstrates an effort by this Salon to promote and cultivate an appreciation for France’s artistic heritage.

Artists battled with the contradictions of the increasingly egalitarian format of these public exhibitions. While they allowed for more opportunity to exhibit, displays still hinged on jurors who gave a stamp of approval which enticed buyers and the general public. Dissatisfied with the lack of autonomy in controlling their careers, artists increasingly called for the modernization of each institution, rejecting self-serving juries who typically supported traditional styles. In protest, artists turned to art forms that purposefully responded to and dissented from art-historical tradition.

But then why, you still ask, do they refuse to send their works to the Salon? If we begin to extricate ourselves from this system, we will never convince other artists to abandon it either.Edmond Duranty, The New Painting, 1876

The exhibitions themselves provided an arena for confrontations between artists and institutions. Flashy and arresting, The Birthday, a recent acquisition, was one of two entries William Holman Hunt presented at the Summer Exhibition of 1869. Although Holman Hunt received his artistic training at the British Royal Academy, he formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with other younger artists, whose aesthetic rebelled against the Academic style championed at the Summer Exhibition.

As one observer noted in The Daily Telegraph’s review of the 1869 exhibition, “Mr. Holman Hunt, who is ‘in’ the Academy as an exhibitor, but, for reasons best known to himself, not ‘of’ it.” The Summer Exhibition provided a forum for Holman Hunt to publicly challenge established techniques and tastes with The Birthday’s vibrant coloring and tactile brushwork.

Alternative Exhibitions

In Paris, a group of artists concerned with visually capturing the momentum of modern life through subject and style mounted a private exhibition in 1874, now known as the first Impressionist show. They sought to capture the essence of contemporary life in canvases that were typically rejected by the Salon, resulting in renegade exhibitions that barred participating artists from submitting works to the Salon.

A New Way of Looking

In London, the progressive Grosvenor Gallery, founded in 1877, was a short-lived alternative viewing space for artists of the Aesthetic Movement who scorned the bureaucratization of the British Royal Academy. It rejected the Summer Exhibition’s cramped hang in favor of a display that gave more space to individual artworks. Prioritizing personal connections between an artwork and its viewers, this style of display grew in popularity throughout the twentieth century and is used at museums today.

While organizing institutions were formative in shaping the public’s judgment of artists and their work, it was ultimately the public that stoked the existence of Salon and Summer Exhibition. Artists motivated to submit art to each exhibition knew what was at stake and created art intended to be seen by the masses, to be gathered around, discussed, and analyzed. Artists strove to find subjects that would resonate and find relevance in the lives of their audiences.

This connection between art and audience was also evident at The de Young Open, which was composed of artworks that spoke to contemporary experiences in the Bay Area. In borrowing a historical display to communicate breadth, The de Young Open also demonstrated how, in many respects, we’ve inherited ways of looking at art that feel unfamiliar but provided frameworks for viewers in the past. The de Young Open brought together a vast array of art that showcased a fresh take on traditional subjects. These artworks facilitated a dialogue between old and new forms of art-making—and looking.