de Young museum

February 16–May 27, 2019

Monet’s earliest paintings inspired by the gardens were studies of flowers. He waited nearly 15 years, as the plantings matured and filled in, before painting broader vistas. In maintaining the gardens, Monet was fastidious, as he knew the landscape would serve as his outdoor studio. The critic Arsène Alexandre once remarked: “His garden. He’s indebted to it, he’s proud of it.”

Monet’s artistic vision knew no limits. After purchasing the property across from his home, Monet set about requesting permission from the local authorities to create a small diversion in the Epte River to create a pond, in which he planned to cultivate aquatic plants. He also requested permission to construct two bridges to cross this water garden. The local neighbors and farmers vigorously opposed the plan, fearing the possible pollution of their water source. A series of letters between Monet and his wife Alice document the artist’s sharp temper and steadfast resolve to achieve his vision. In one letter, Monet exclaims, “To hell with the natives of Giverny.” Years later, he again engaged with the local government, paying for all the roads in town to be paved to alleviate the dust that constantly contaminated the leaves of his water lilies.

At the height of his work in the gardens, he employed eight gardeners and spent about 40,000 francs a year in plantings and upkeep.

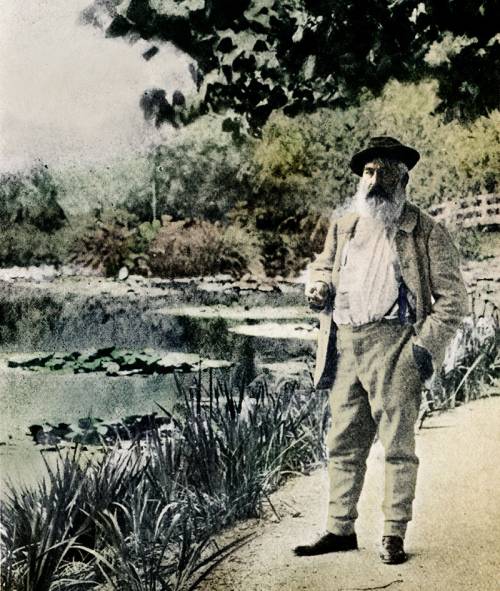

From a very early age, Monet loved gardening, and he tended to the gardens at his homes before moving to Giverny. He once stated, “Beyond painting and gardening, I am good for nothing.” Upon taking possession of his Giverny home, called Le Pressoir (the Cider Press), Monet set about a massive redesign that slowly took shape between 1883 and 1899.

His first order of business was to remove the kitchen garden at the front of the house and to update the plantings, giving particular attention to creating tones and color fields, in the two-and-a-half-acre walled garden behind the house. For Monet, who in his early career frequently experienced financial hardships, the garden—both its creation and its upkeep—amounted to a luxury.

The artist installed his wooden Japanese-style footbridge in 1895, aligned with the grande allée, the arbor-covered pathway leading to the main entrance of his house.

“It took me some time to understand my water lilies. . . . I cultivated them with no thought of painting them. . . . And then, suddenly, I had a revelation of the magic of my pond.” —Claude Monet

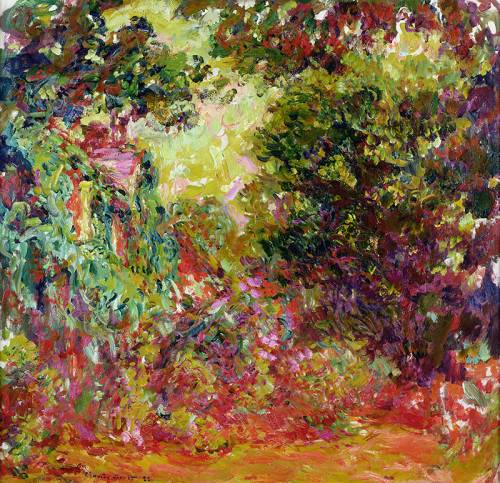

Monet returned to the subject of the Japanese bridge later in his career, treating it with bravado on a larger scale, with intense colors and gestural brushwork.

In the final years of his career, Monet’s attention increasingly focused on the multiple visual effects of his lily pond, which he used as an instrument for radical artistic development. In 1903 Monet undertook his first series devoted to water lilies. Monet’s observations of his pond extend beyond the visual, becoming metaphorical statements about the transformative power of nature.

These canvases, painted while the artist was in his 70s and 80s, are often so large that they cannot be seen in a single glance. Monet’s stepdaughter Blanche, nicknamed “the Blue Angel” for her blue eyes and endless patience, served as Monet’s chief assistant, moving canvases about his studio. At times his gardeners would help bring canvases to the gardens.

Monet achieved complicated effects through his studied examination of reflections. In 1908 he remarked, “These landscapes of water and reflections have become an obsession.”

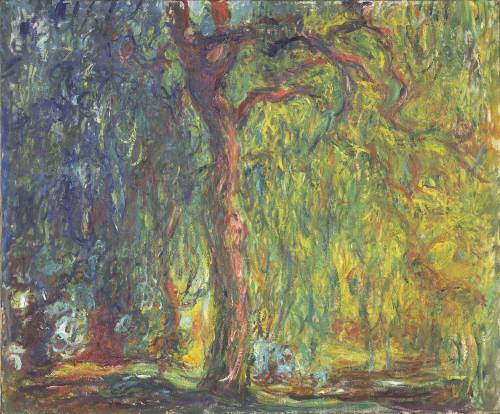

From the start, Monet was an accomplished colorist, leading his contemporary Paul Cézanne to declare, “Monet is nothing but an eye, but what an eye.” His late compositions show broad, energetic brushstrokes of vibrant color that float on the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Other examples are so vibrantly colored that they elude a direct connection with nature and suggest pure sensory experience in its place.

With references to a horizon line reduced and then eliminated, the paintings become celebrations of color and form, anticipating later art movements of the 20th century.

Monet’s late depictions of his gardens are characterized by marked changes in his use of color, which might be explained in part by his vision problems. The artist was diagnosed with cataracts in 1912, at age 72, but his eyesight had begun to fail several years earlier. At this time, his brushstrokes became broader, and his hues became darker and muddier, with more brown, yellow, and purple. Fearful of cataract surgery, Monet turned to lenses and eye drops to improve his vision but eventually capitulated to surgery in 1923. After a long recovery and the use of new special lenses that completely covered one eye, he was confident enough to retouch some of his previous works and return to his most important projects.

To judge from his copious correspondences, Monet’s creative process was intertwined with self-doubt. In an 1890 letter to fellow artist and friend Berthe Morisot, Monet exclaimed, “This blasted painting is tormenting me and I can’t do anything about it. I am just scratching and wearing out canvases.” Time did not relieve Monet’s anxiety. His letters with Georges Clemenceau document the artist’s constant misgivings and the elder statesman’s unfailing encouragement to keep working. At times Monet’s anxiety would turn into anger, which he exercised against his canvases. In 1908 Lilla Cabot Perry, an American artist, reported that Monet burned 30 canvases. Others who visited the artist’s studio reported seeing canvases with knife gashes ripped through the compositions.

When I have no longer need to sell, I have managed to work; now, I think I am as hard on myself as it’s possible to be.—Claude Monet

Despite his misgivings, Monet’s late work also attests to his unfailing work ethic and compulsion to create. In his later years the necessity to work seems to be intertwined with the artist’s awareness of his mortality. In his garden, Monet achieved his greatest challenge, the constant advancement of painting. These varied compositions, crowned by the larger scale Grandes Décorations, gave Monet a reason to exist.

Color is my day-long obsession, joy, and torment.Claude Monet to Georges Clemenceau, quoted in Clemenceau’s Claude Monet: Les Nymphéas (1928)

Recounting his experience of seeing a Monet haystack in 1896, Wassily Kandinsky stated in 1913 that “objects were discredited as an essential element within the picture.” He went on to explain that Monet’s compositions relied upon the “power of the palette” and the use of color for its own sake.

As a young art student in the 1890s, Henri Matisse diligently studied Monet’s work, even going so far as to paint in some of Monet’s favored locations. On May 10, 1917, Matisse successfully managed to meet the famously reclusive artist. The artist painted The Music Lesson just a few months later.

While studying in Paris under the GI Bill, Ellsworth Kelly contacted Monet’s stepson Jean-Pierre Hoschedé, requesting to visit Giverny. Of the experience, Kelly recounted, “There must have been at least a dozen canvases . . . each on two easels. . . . The paintings were more or less abandoned.” The following day Kelly composed Tableau Vert.

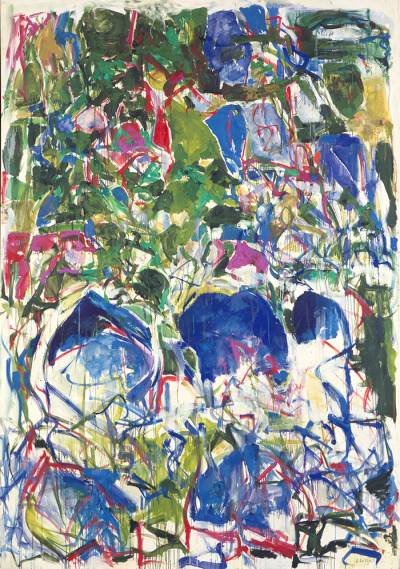

In 1967 the Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell purchased a property in the French coastal village of Vétheuil. The gardener’s cottage on her property once served as Monet’s home. On this basis, critics and historians alike drew comparisons between their works. Mitchell ardently denied Monet’s influence, stating her paintings were “about a feeling that comes to me from the outside, from landscape.”

Over the course of his long career, Monet witnessed the development of modernism, which both built upon and challenged his aesthetic vision. As Post-Impressionist artists such as Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent van Gogh transformed the art world, paving the way for the modernist art movements of the 20th century, Monet continued to advance his own style. After his initial introduction of a revolutionary use of color and bold brushstrokes, Monet started painting in series in 1891. His first exhibition of serial works featured compositions of haystacks in the fields surrounding Giverny. Creating a series of works focused on a single subject allowed Monet to demonstrate the level of exacting observation and meticulous skill involved in capturing changes in weather, atmosphere, and light. These works in part silenced critics who had accused the Impressionists of being overly spontaneous and haphazard.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Monet continued to evolve his style. While Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, and Fernand Léger made headlines with their own artistic visions, which minimized the importance of observing nature, Monet remained steadfast in his focus on his gardens. He brought vitality and interest to his work by evolving his brushstroke, which became broader and more layered, and significantly expanding the scale of his compositions. These stylistic innovations would crystalize in the artist’s most ambitious project, the Grandes Décorations, installed in the Musée de l’Orangerie in 1927, after the artist’s death, as a gift to the French state.

In 1883, at the age of 43, Monet settled in Giverny, France, a small village of no more than 300 inhabitants, with his two sons; his companion (soon to be second wife), Alice; and her six children. A direct train line provided easy access to Paris, just 45 miles away. Life in Giverny offered Monet unprecedented happiness and prosperity. However, by 1914 Monet had endured the debilitating loss of Alice and subsequent death of his eldest son, events that contributed to a nearly two-year hiatus from painting.

Throughout his career, Monet kept works that held personal significance. Toward the end of his life, Monet displayed these works in one of his studio buildings, as seen in the photograph below. In it Monet and a guest study a fragment of the composition Luncheon on the Grass (1865–1866), painted when he was in his mid-twenties. This nearly life-size canvas is pictured hanging alongside works he painted from 1887 to 1919.

Feeling a sense of mortality and knowing the “heroic years” of Impressionism were behind him, Monet increasingly focused on his art historical legacy.

Close study of Monet’s brushstrokes in Weeping Willow reveals that the artist worked in multiple layers, applying some wet on wet and others after the paint fully dried. Despite Monet’s emphasis on his work “in the field,” his working process always included time in the studio. In fact, at Giverny Monet constructed three increasingly larger studios in which to work.

[Nature] is greatness, power, and immortality beside which creatures seem to be no more than miserable atoms.Claude Monet, June 1909 (Roger Marx, Gazette des Beaux Arts)