Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books

Legion of Honor museum

Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books

Legion of Honor museum

Mme. Delaunay has made such a beautiful book of colors that my poem is more saturated with light than is my life. . . . Besides, think that this book should be two meters high! Moreover, that the edition should reach the height of the Eiffel Tower!Blaise Cendrars in Der Sturm (Berlin), September, 1913

Delaunay-Terk (1885–1979) was born in Ukraine and raised in Saint Petersburg. She moved to Paris in 1905. In 1910 she married Robert Delaunay, an artist known for his bold use of color and abstract form. The Delaunays were exemplars of Orphism, as the poet Guillaume Apollinaire called it, their work infusing Cubism with dynamic light and color. In addition to painting, Delaunay-Terk’s practice encompassed textile and fashion design, bookbinding, furniture design, and set design.

Cendrars (1887–1961) was born Frédéric-Louis Sauser in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and became a French citizen in 1916. One of the leading literary figures of twentieth-century France, he was a friend of and collaborator with many artists, including Fernand Léger, Marc Chagall, and Amedeo Modigliani.

A woman nearby, covered by diamonds, but the music of Stravinsky drove her crazy, tore out a brand new folding seat and smashed me over the head with it, so I had to spend the rest of the night drinking champagne in Montmartre with Stravinsky [and] Diaghilev . . . still wearing the folding chair like a horse collar...Blaise Cendrars, radio interview, 1950

Rarely had there been a time when artists felt so emboldened to disregard rules and traditions. The disruptive clash between more orthodox expression and that of the avant-garde was the defining spirit of the time (the battlefields of modernism in their own way foreshadowed the battlefields of 1914, when many artists and poets – including Leger, Cendrars, and Apollinaire – eagerly enlisted for combat). Perhaps no event was more characteristic of the time than the explosive premiere of Sergei Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky’s ballet, The Rite of Spring, vividly described by Mary Ann Caws and Blaise Cendrars in the texts that follow.

La prose was a product of its time and place, a period like no other before or since. Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso were creating the radical new artistic vision of Cubism, leading to the birth of abstraction, and Marcel Duchamp was brewing his own conceptual artistic revolution. In poetry, Guillaume Apollinaire was charging through the door that Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898) had opened with his sophisticated exploration of visual poetics. Russian emigrés were injecting energy and radical ideas into the mix, bringing with them the bold dynamics of Futurism. The modernist spirit that was centered in Paris extended to all of Europe and the world beyond, setting the stage for the advent of Dada and Surrealism.

It was not the art dealers, nor the critics, nor the collectors who made these painters famous, it was the modern poets, and people forget it rather too easily, and so do all these painters who, today, are millionaires and are still indebted to us, the poor poets!Blaise Cendrars, La lotissement du ciel (Sky), 1949

The year 1913, on the cusp of the Great War, was a kind of fulcrum in time, and Paris was the balance point.

Mallarmé (1842–1898) is widely credited with opening the field of modernist visual poetics with his poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance). He was a major influence on many of the poets, and even visual artists, of the generation that followed, an influence that is still felt today.

One Toss of the Dice was the birth certificate of modern poetry.R. Howard Bloch, One Toss of the Dice, 2017

Apollinaire (1880–1918) was the quintessential poet of modernism. Immensely influential among his contemporaries, both poets and artists, he helped define the avant-garde in both art and literature, and coined the terms Cubism and Surrealism.

[Apollinaire] marks an epoch. The beautiful things we can do now!

Jacques Vaché, letter to André Breton, 1918

A sad poem printed on sunlight.Blaise Cendrars

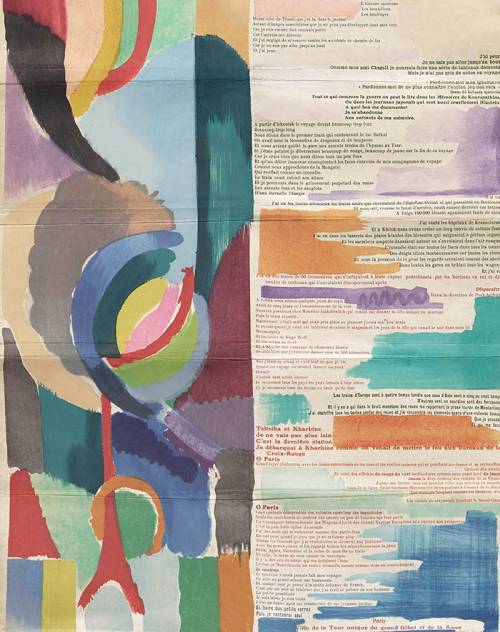

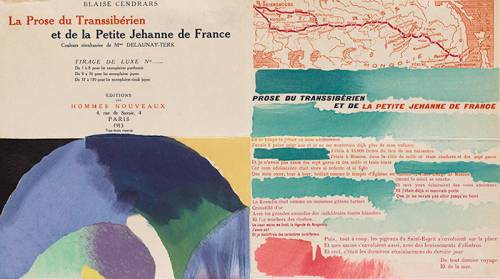

The book is a vortex of convergent and oppositional energies, an environment created for a remarkable reading experience. When folded it is roughly four by seven inches, and just over an inch thick. If unfolded on a long table to full length, more than six feet, the entire design and text can be apprehended—not, as Apollinaire said, at a glance, but by following the poetic narrative as it weaves through splashes of color. Folded a different way, it can be read section-by-section, as in the animation at the bottom of this site.

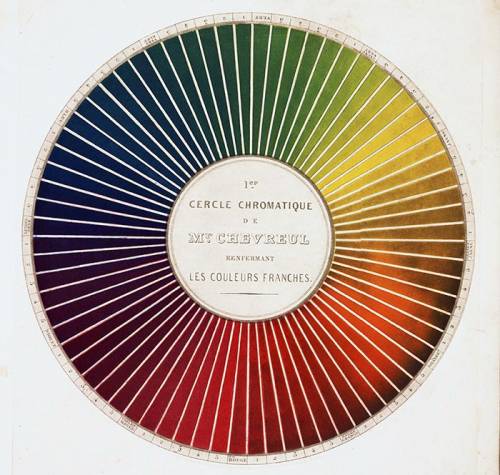

Mary Ann Caws explains a source for Robert and Sonia Delaunay’s experiments with chromatic simultaneity.

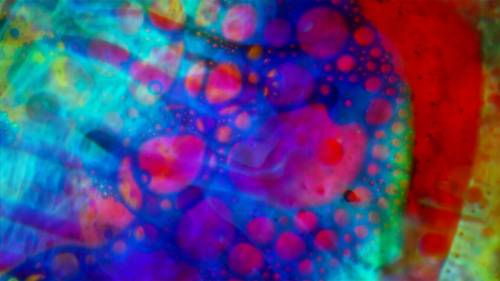

La prose is at once a simultaneous riot of colors, as both painter and poet intended, according to the authors' acquaintance with the theories of Michel-Eugène Chevreul, author of De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs (The Laws of Contrast of Color), 1839. Chevreul experimented with a color wheel, and his discoveries had a great influence on the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists, and, in turn, on the whirling colors of this brightly-lit scroll of a poem.Mary Ann Caws, 2017

Blaise Cendrars describes the kind of experimentation Robert and Sonia Delaunay were undertaking at the beginnings of modernist abstraction in painting.

[Robert Delaunay] closed the shutters and shut himself up in his dark room. . . He made a little hole in the shutter with a brace and bit. A thin ray of sunlight filtered into the [room] and he began to paint it . . . to analyze all its elements of form and color. Without knowing it, he was doing spectrum analysis. He worked for months like this . . . reaching the sources of emotion without any subject matter whatever.Blaise Cendrars, Aujourd’hui, 1931

Marjorie Perloff

Professor Emerita at both Stanford University and the University of Southern California

Marjorie Perloff is the author of many books on poetry and poetics, including The Futurist Moment: Avant-Garde, Avant-Guerre, and the Language of Rupture(1986), which deals extensively with artists and poets in the years leading up to WWI.

La prose du Transsibérien is a text full of contradictions. The title, for starters, is odd: it should be “le prose” and, even then, why call a lineated lyric “prose”? Cendrars declared that he used the word “prose” so as to open up the discourse; then, too, the poem is “dedicated to the musicians”—evidently those new musicians of the period, such as Eric Satie or Igor Stravinsky, who were avoiding all conventional rhythms. The long free-verse lines, with their paratactic structure and repetition, remind one of Walt Whitman, but the voice of this poem is hardly Whitman’s oracular one. Rather, Cendrars stresses immediacy, nervous energy, and excitement:

In creating an authentic facsimile edition, artist and educator Kitty Maryatt has conducted exhaustive research into the production processes used for La prose in 1913.

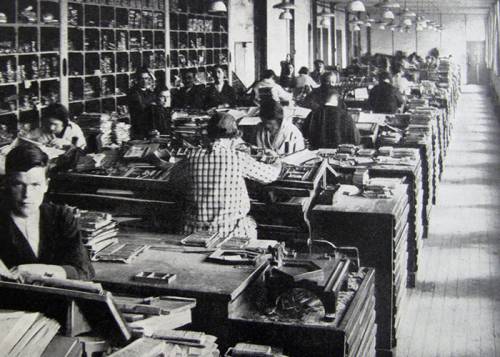

Kitty Maryatt has identified 30 separate typefaces used in the typographic composition for the poem. The book was printed at Imprimerie Crété, then the largest printing facility in France. Cendrars provided detailed instructions for the compositors, most likely by consulting Crété’s type-specimen catalogue.

Sonia Delaunay first painted the image for La prose on mattress ticking. The image was reproduced for the edition by pochoir, a stencil process, with color applied by hand using prescribed brush strokes, exacting manipulation of stencils, precise registration, and consistent color matching. It is likely that the pochoir was performed at Crété.

The book appropriated the form of a folded map, with the poem unfolding to more than six feet vertically. A map of the route of the Trans-Siberian Railroad was included at the top corner of the layout. It was designed to first unfold with only the blank back side showing so that it could then be dramatically opened to expose the contents all at once, in keeping with the precepts of simultaneité. It is thought that only 30 copies were enclosed in a hand-painted vellum cover.

There were to be 150 copies in total, but it is likely that only about half that many were produced. A prospectus announced eight deluxe copies printed on vellum, 28 on japon (imported Japanese) paper, and, for the standard trade copies, simulated japon (similé japon). Maryatt has identified the Logan copy at the Legion of Honor, with its crisp letterpress printing, as one of the rare copies on japon.

In some respects, the poem resembles Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. In composition, they share a common conceit: the illusion that they were composed, or narrated, in a single sitting, the intimate testimonial quality of a tale of alienation and transgression drawing the listener or reader in. Both are road-trip stories, with socially marginalized traveling companions, that move across vast landscapes. Both are simultaneously life-changing inward journeys. And anyone who has seen the Kerouac manuscript, the scroll, will immediately recognize the physical resemblance. With visual art, though, the two reading experiences diverge, and it is the hybrid nature of what we are looking at that distinguishes La prose as a unique and transcendent experience for the reader and viewer.

The interplay of colors and the synesthetic illusion of movement in Delaunay’s pochoir has an uncanny parallel in the psychedelic light shows of the 1960s, where bright, pulsating, liquid forms merged with an experience of rhythmic sound, as the rhythms of Cendrars’s lines—dedicated, as he said, “to the musicians”—seem to emerge from the artist’s abstract color-forms.

The steady growth of the field of book art in recent decades finds an iconic predecessor in La prose. Its unique appropriation of structure and its hybrid nature have made it an influence on succeeding generations of artists and writers who take the book beyond the limits of conventional form. For his spectacular Nature Abhors, Philip Zimmermann used a structure devised by influential book artist Hedi Kyle—seen here in an animation by Radek Skrivanek.

The forward-looking nature of La prose has many parallels in our time.

Over a period of 20 years the Chicago collectors Reva and David Logan built one of the great private collections of artists’ books, and in 1998 donated that collection to the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, home of works on paper at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

With more than 400 carefully assembled titles, the Logan Collection contains many of the most important works in the genre, with significant artists’ books representing virtually every major art movement dating from the beginnings of the livre d’artiste in the late nineteenth century. Augmented by important works already held by the Achenbach Foundation, the Logan gift established the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco as stewards of one of the most historically significant collections of artists’ books in the United States.

As the only works of art that must be handled to be fully experienced, artists’ books present a challenge for an institution charged with their conservation and display. The current project, funded by a generous grant from the Reva and David Logan Foundation, addresses this challenge by making contents of, and related information about, selected books from the collection available online using the capabilities of digital media. The project aims to raise the profile of the collection and create greater public understanding and awareness of what critic and historian Johanna Drucker has called arguably “the quintessential twentieth-century art form.” This project intends to make significant works by many of the most important artists of the century available for public access in their entirety for the first time.

Mary Ann Caws

Distinguished Professor Emerita, Graduate School of the City University of New York

Mary Ann Caws is the author of more than 40 books, including The Surrealist Look: An Erotics of Encounter (1997), and Picasso’s Weeping Woman: The Life and Art of Dora Maar (2000).

The cacophonous Rite of Spring was the centerpiece of a simultaneity of sound, color, and movement. Nijinsky danced its May 29 premiere for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris’s Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, and the spectacle provoked a celebrated pandemonium. Igor Stravinsky’s discordant music touched off outrage from the more conservative audience members, with others equally vehement in its defense. This riot against modernism, to put it bluntly, conferred on the piece more glory than anything positive could possibly have done—riots led to revelry in the long run.