Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books

Legion of Honor Museum

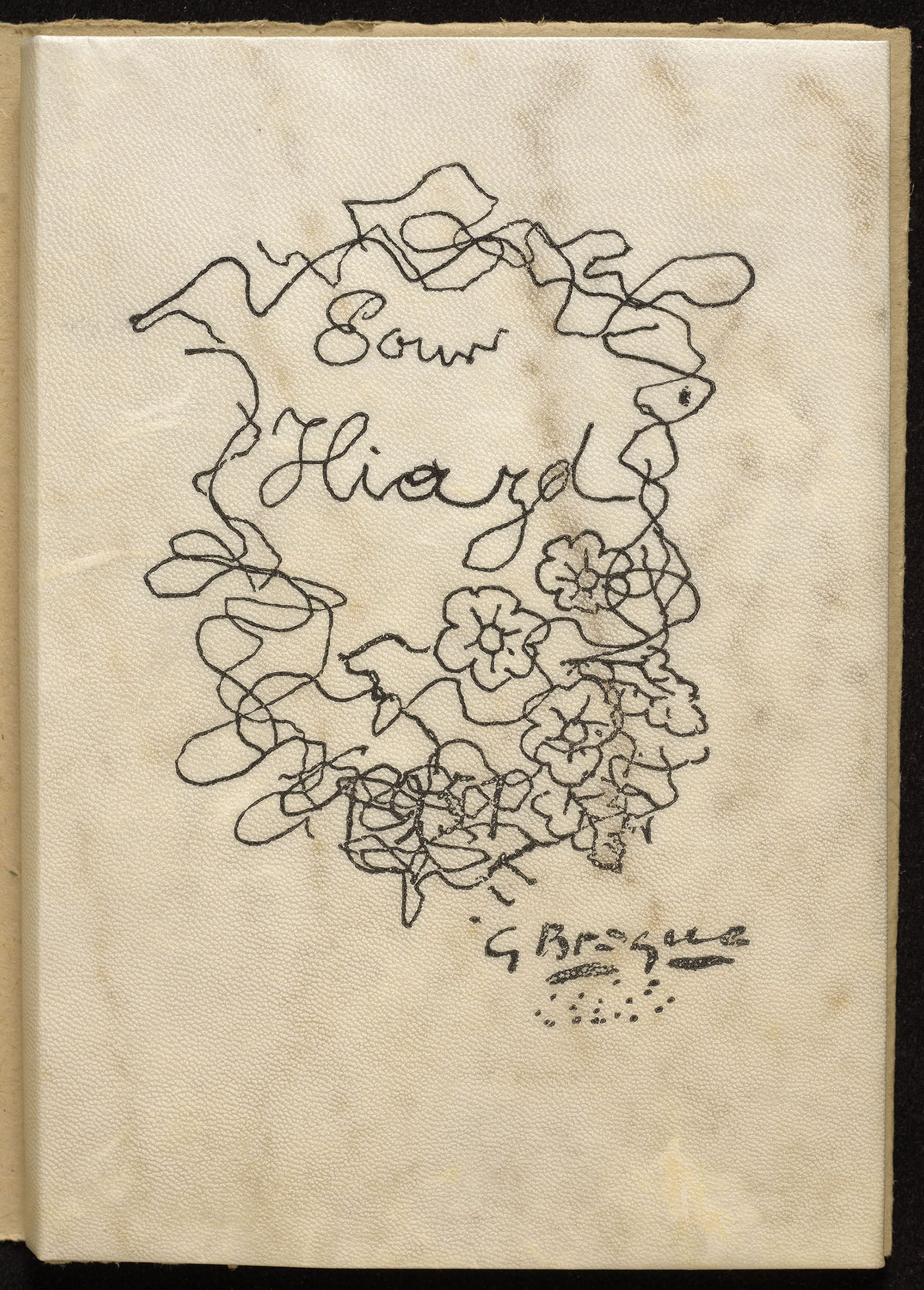

Iliazd

Publishing as an Art Form

Introduction

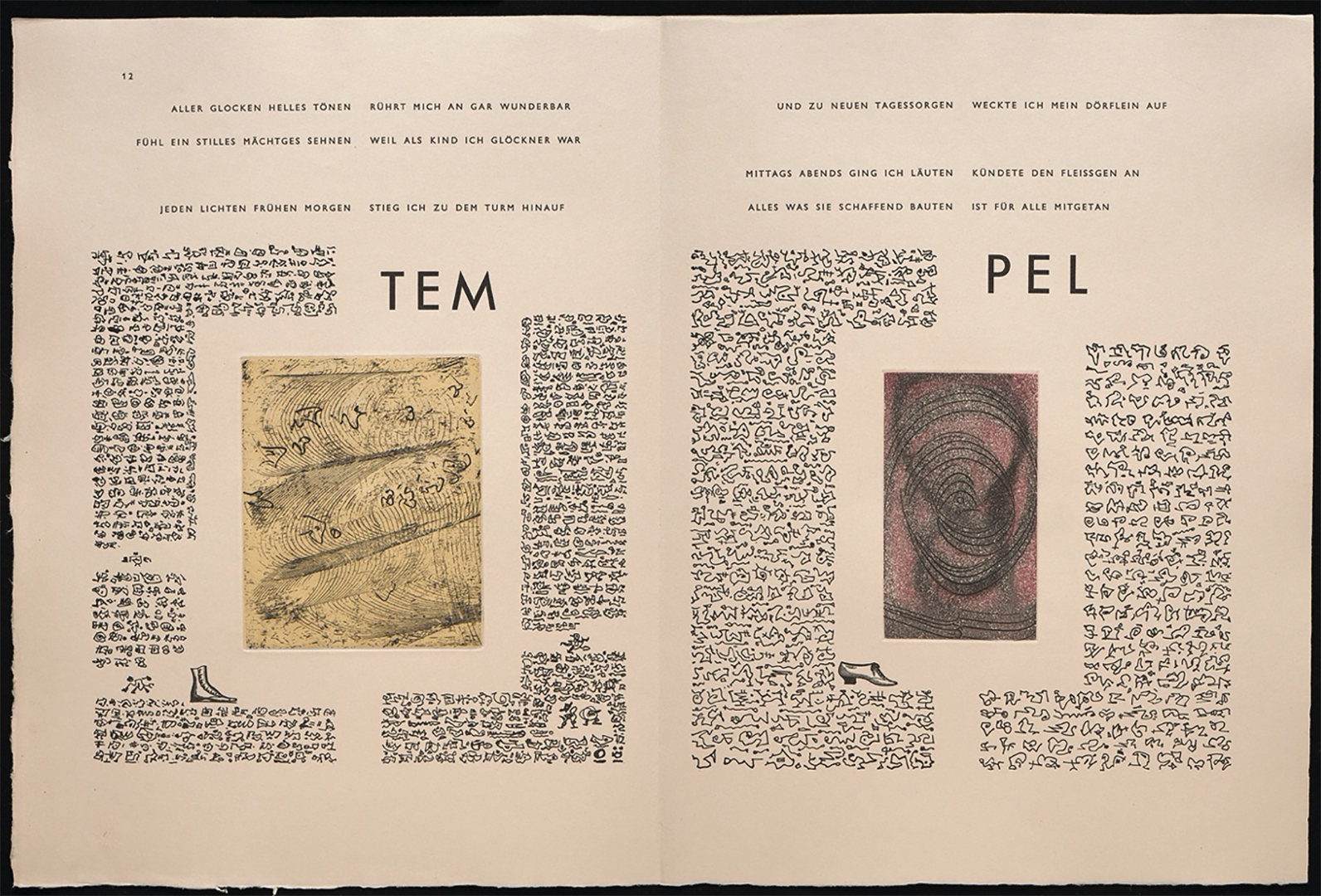

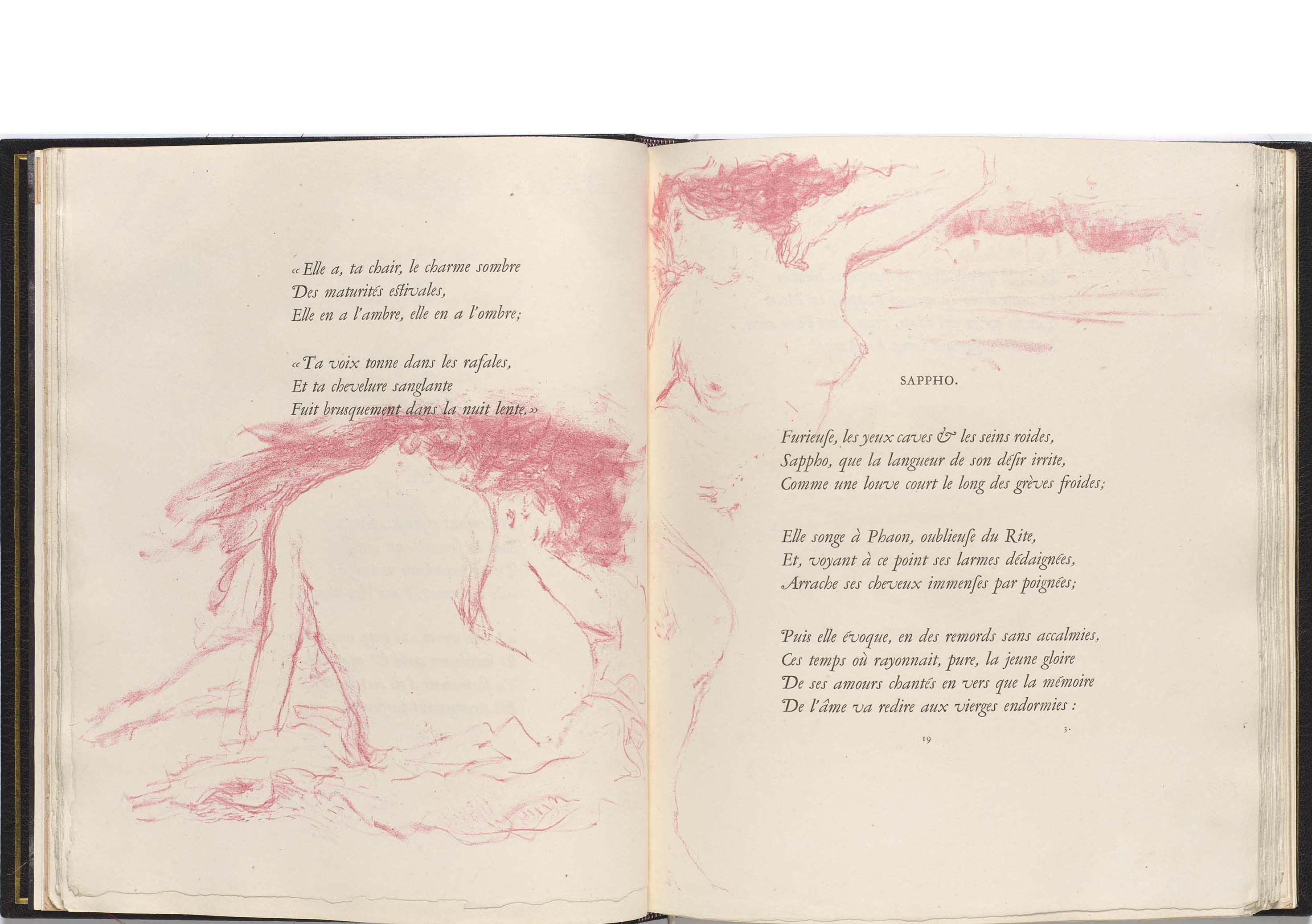

The term livre d’artiste, literally “artist’s book,” originally denoted a publishing practice by art dealers early in the twentieth century through which they showcased the work of artists they represented. These luxury editions, marketed to collectors of fine art, featured original prints illustrating a classical or contemporary text.

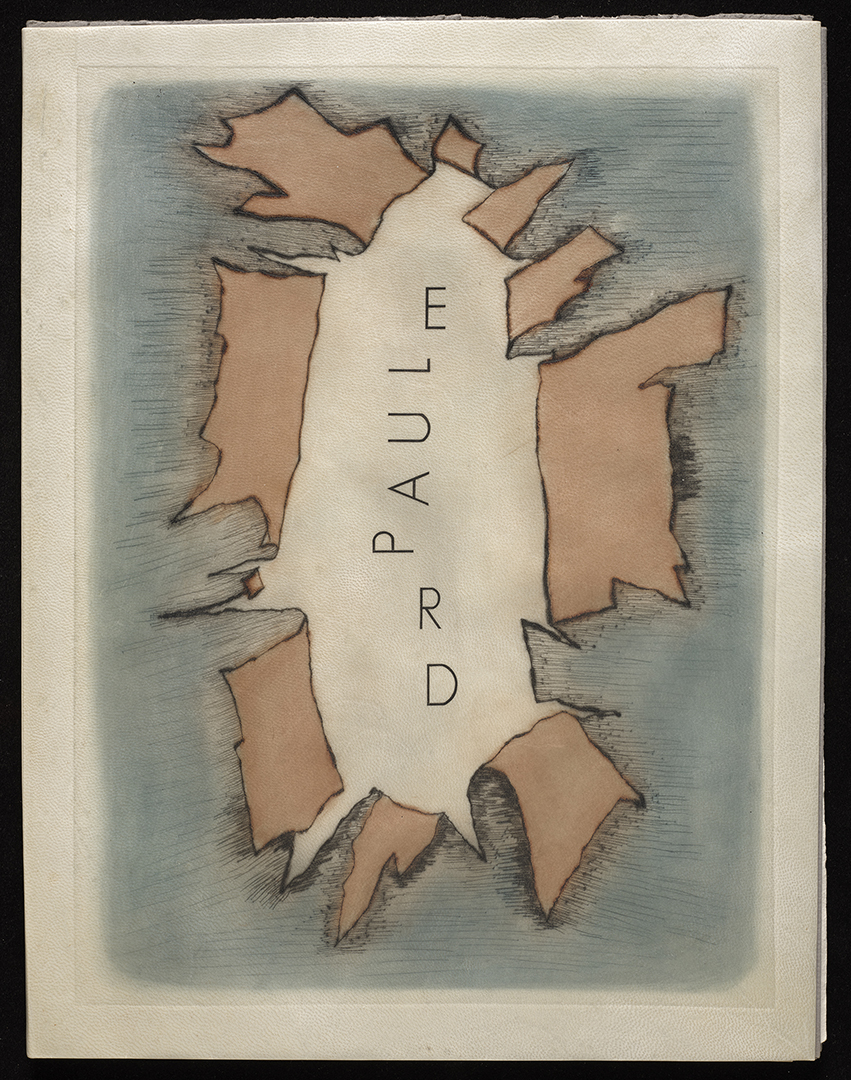

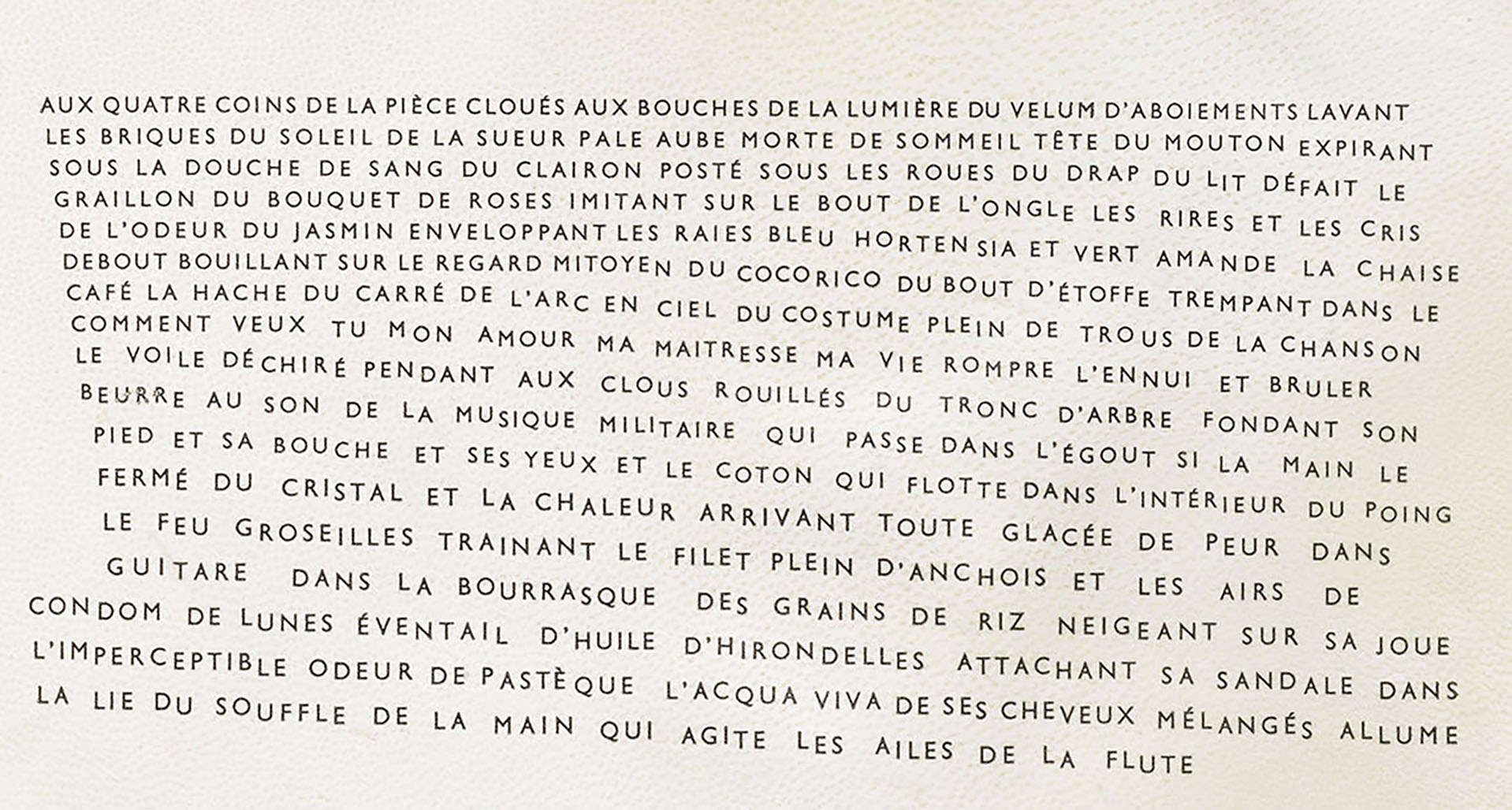

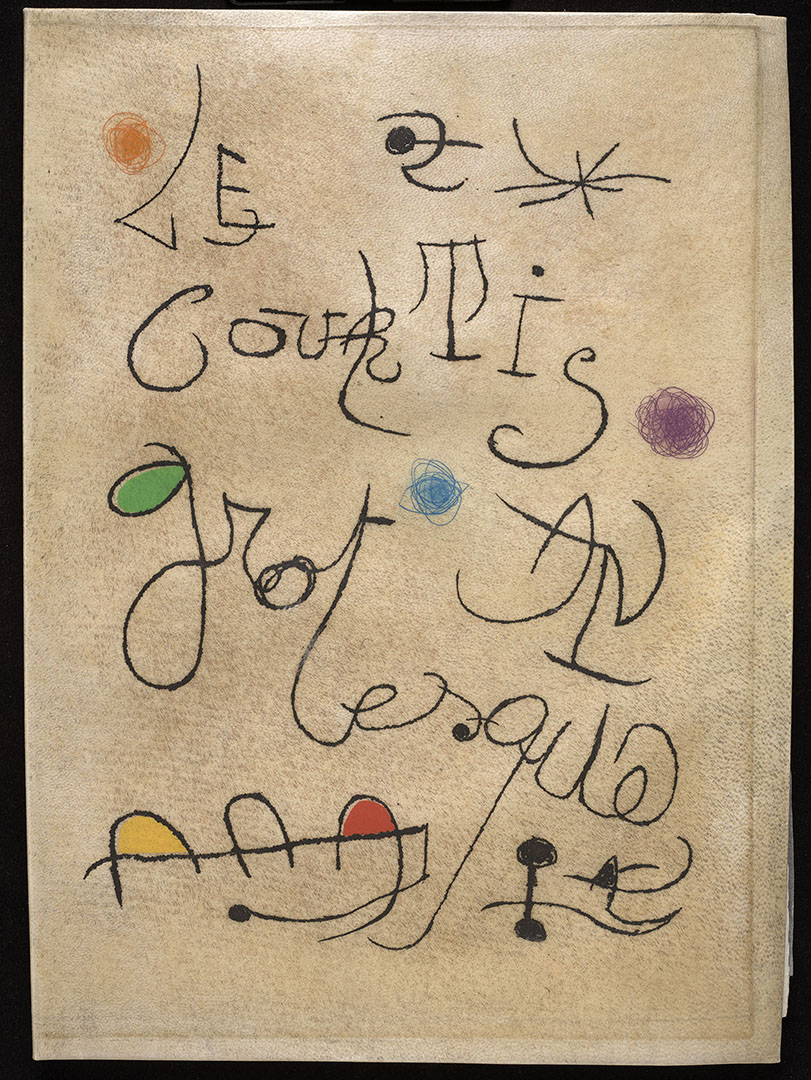

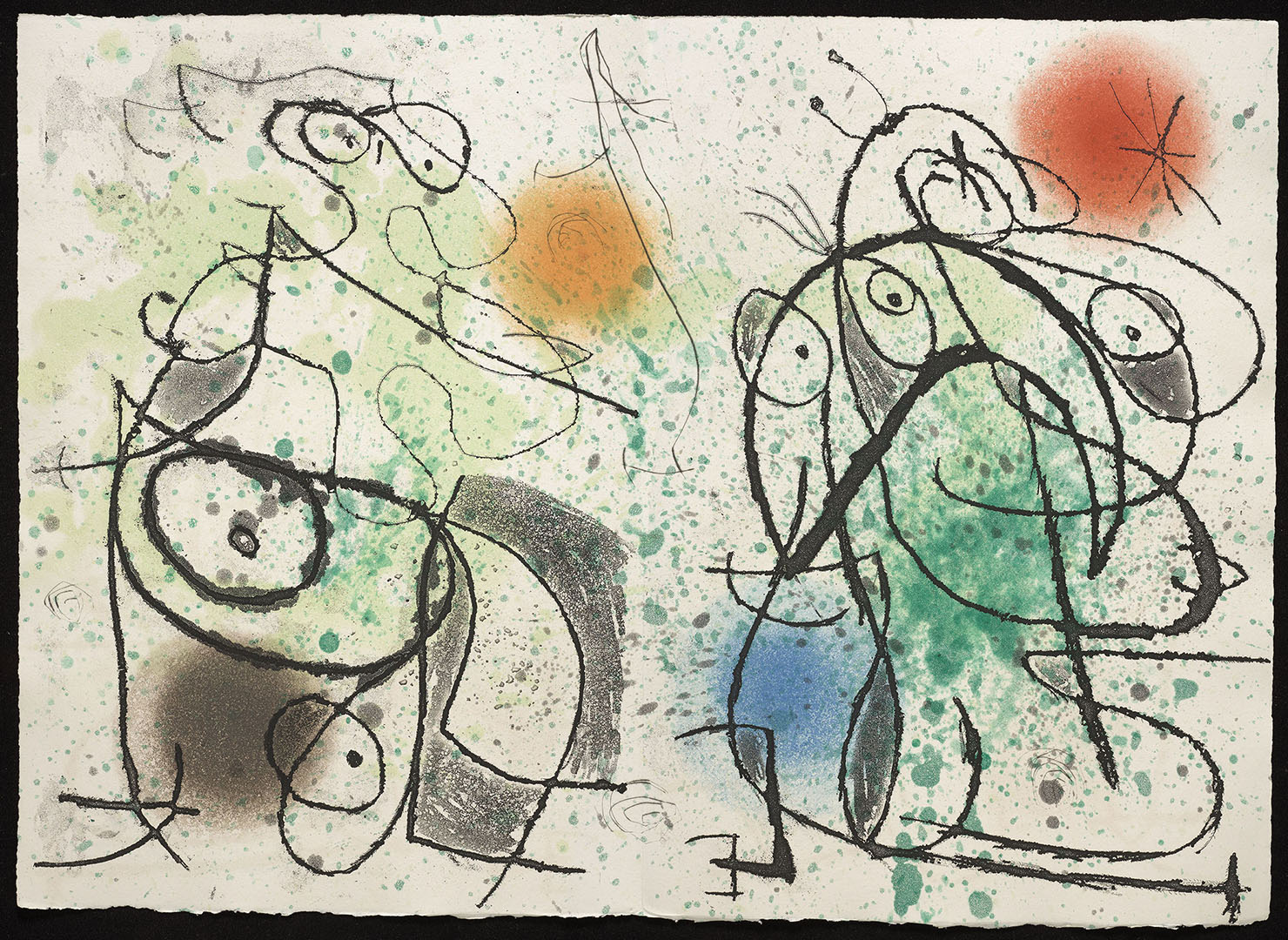

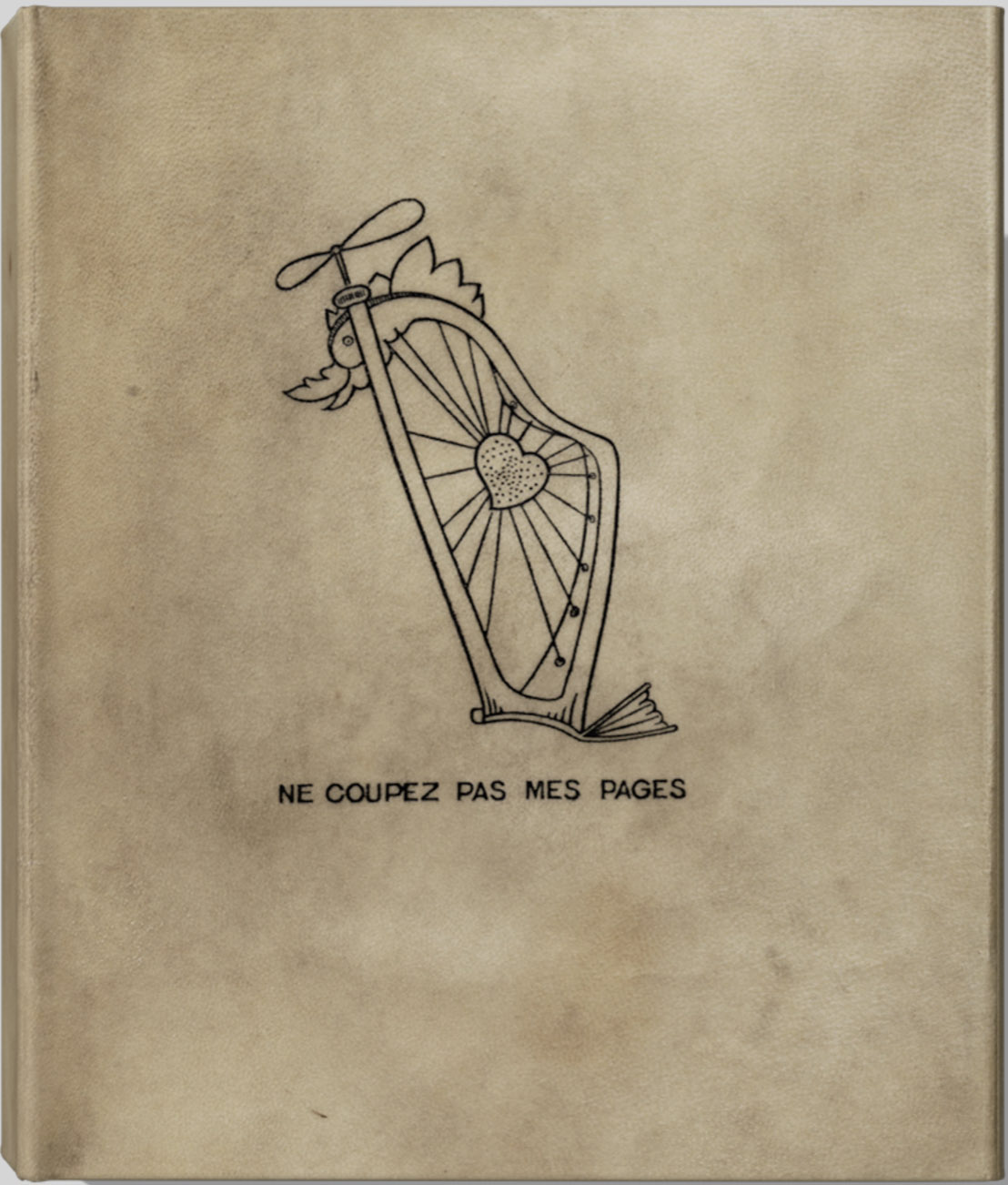

Though Iliazd’s books have been classed with livres d’artistes, he was not an art dealer but an artist working in collaboration with other artists. He was arguably the first “book artist” in our contemporary sense of the term, an artist for whom the book itself was the art medium in a practice sustained over decades.

An illustrated book by Iliazd is a book by Iliazd, and not a book by Picasso, Miró, or Max Ernst. . . . a standalone work of art just like a painting, a sculpture, a monument, a film. And Iliazd is its true and sole creator.Louis Barnier, director of the Imprimerie Union, the Paris studio where Iliazd printed his books

Bulletin du Bibliophile, 1974

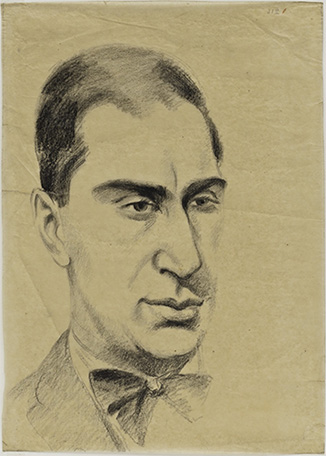

Ilia Zdanevich had grown up in an environment of high culture, in a time when revolution was in the air. His father was a teacher of French, his mother a connoisseur of art and music who had studied with Tchaikovsky, and his older brother, Kirill, an artist. At age seventeen, Ilia left his home in Tiflis, Georgia, and moved to Saint Petersburg, ostensibly to study law. Upon his arrival, Kirill connected him with the artists and poets of the burgeoning avant-garde, and soon Ilia was swept up in an atmosphere of revolution in the arts.

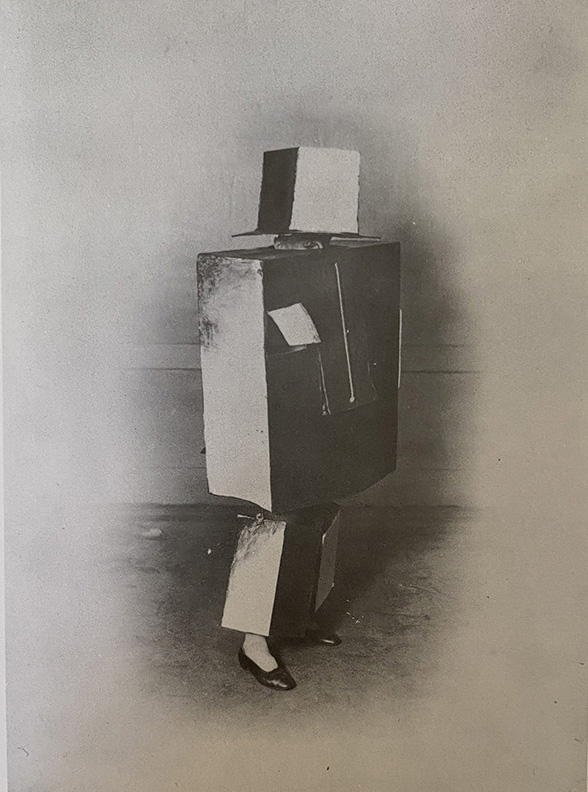

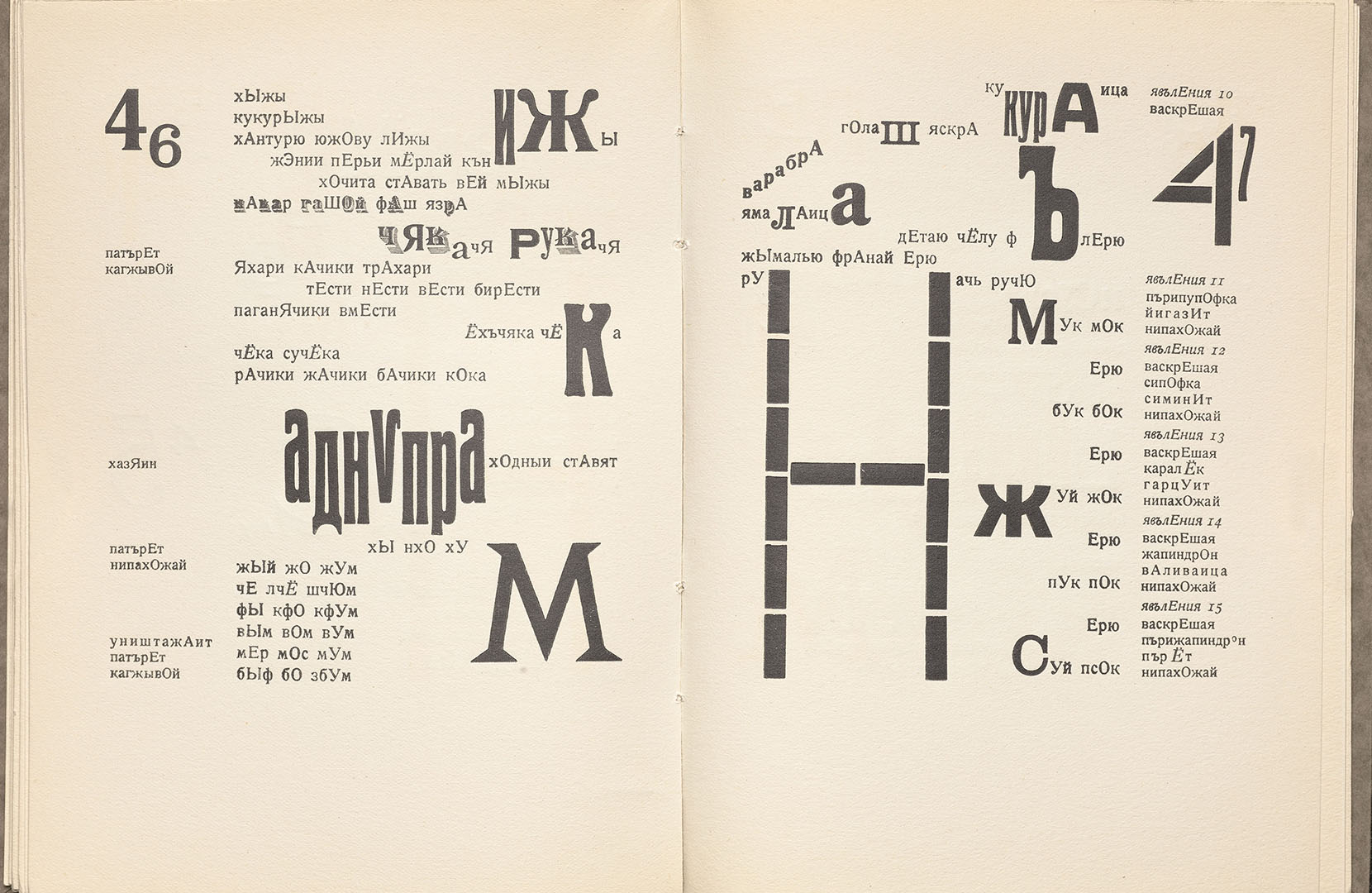

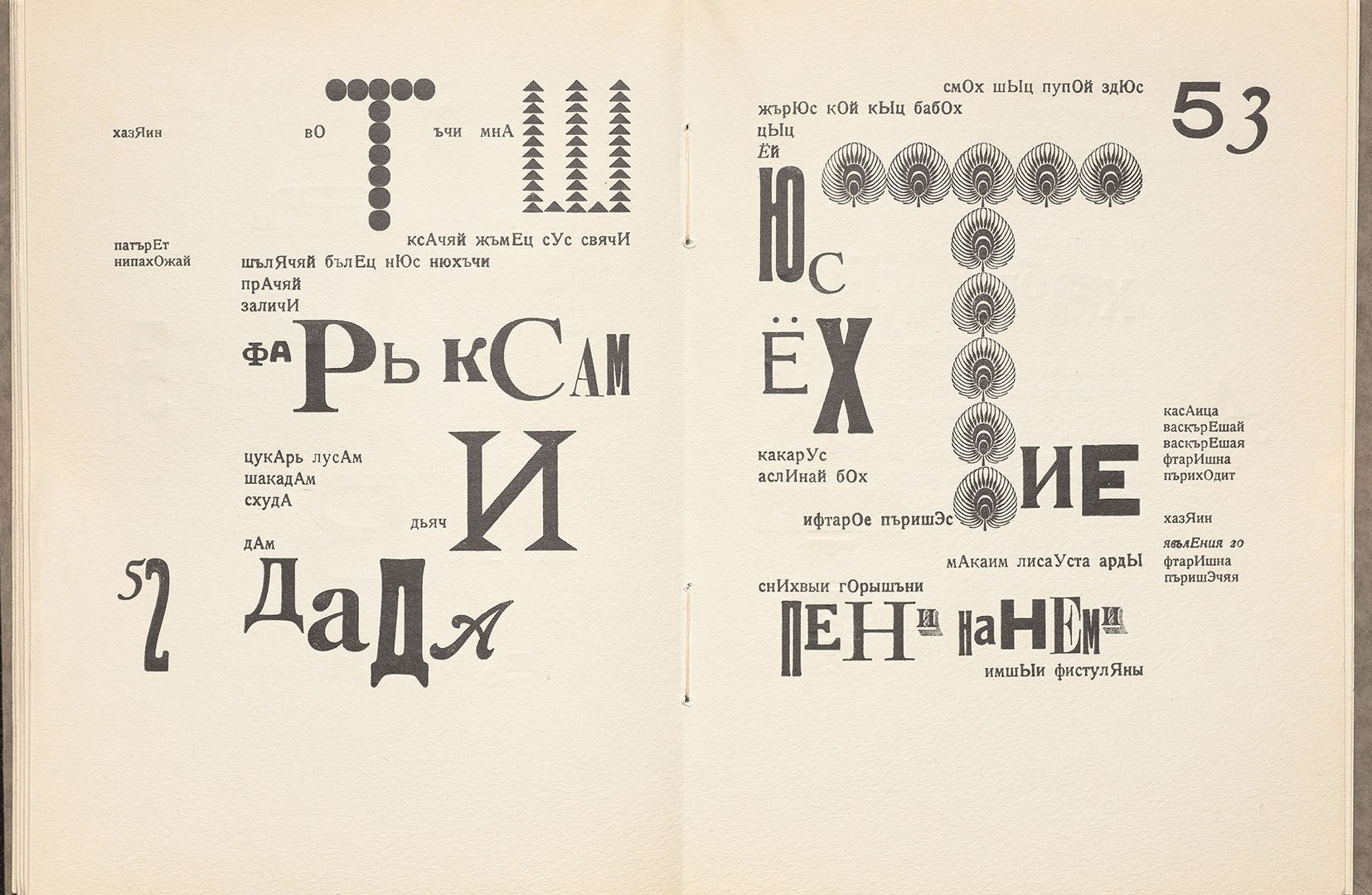

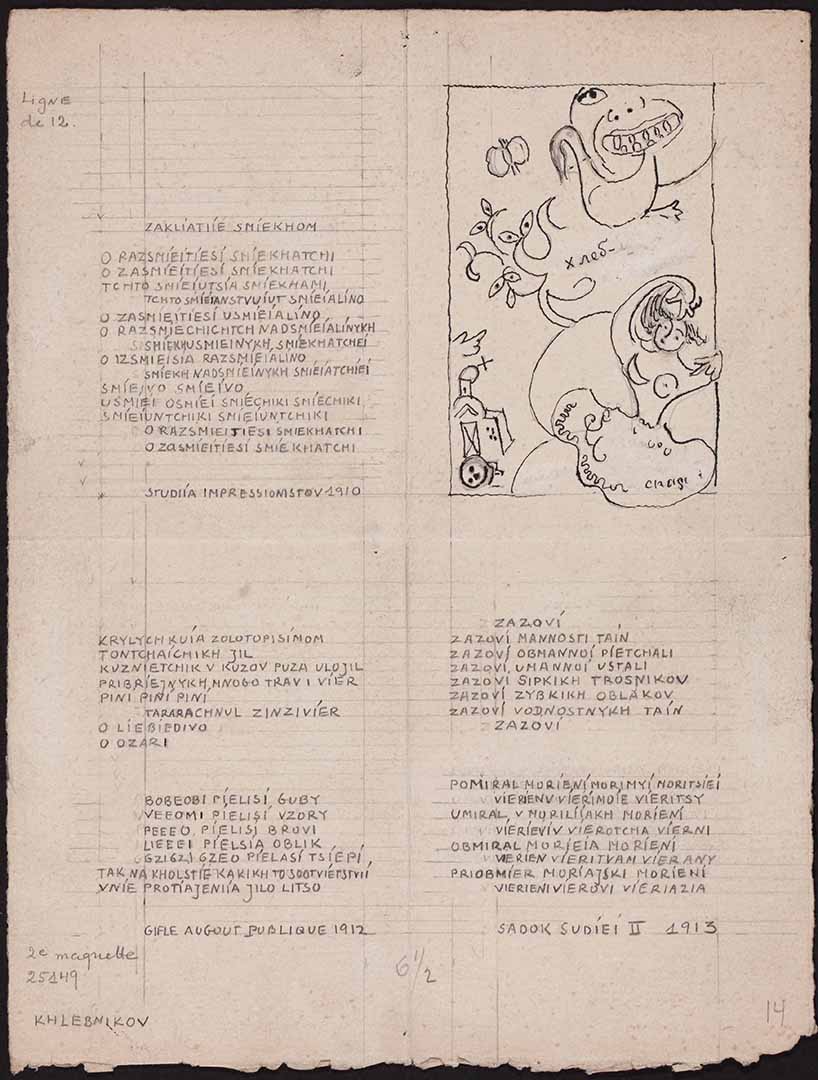

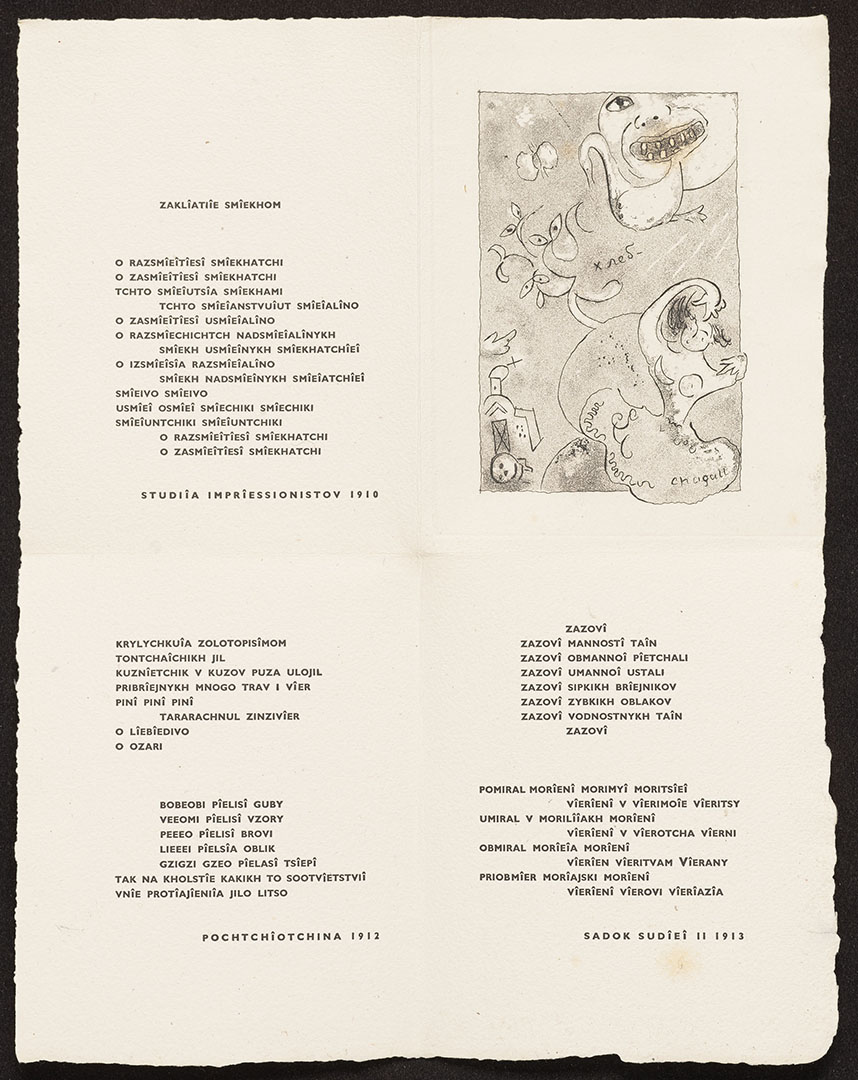

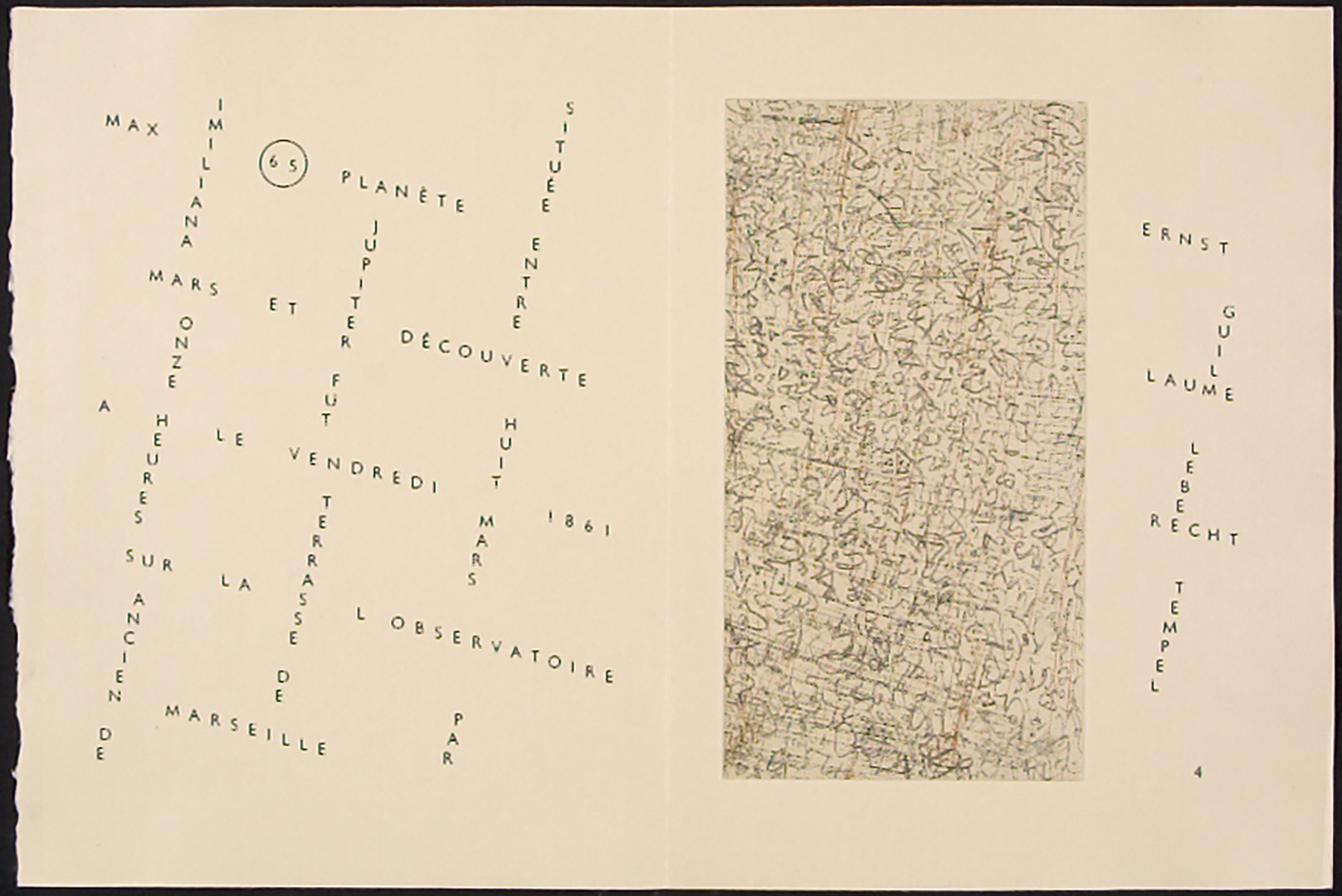

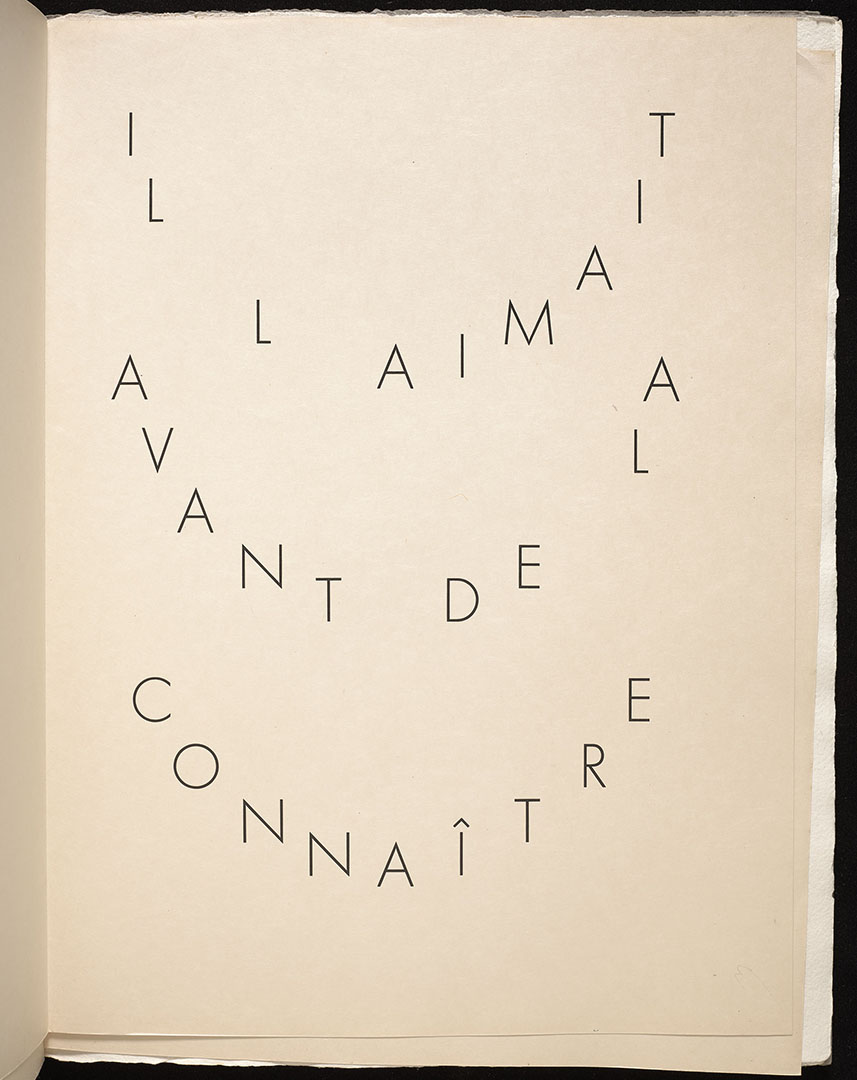

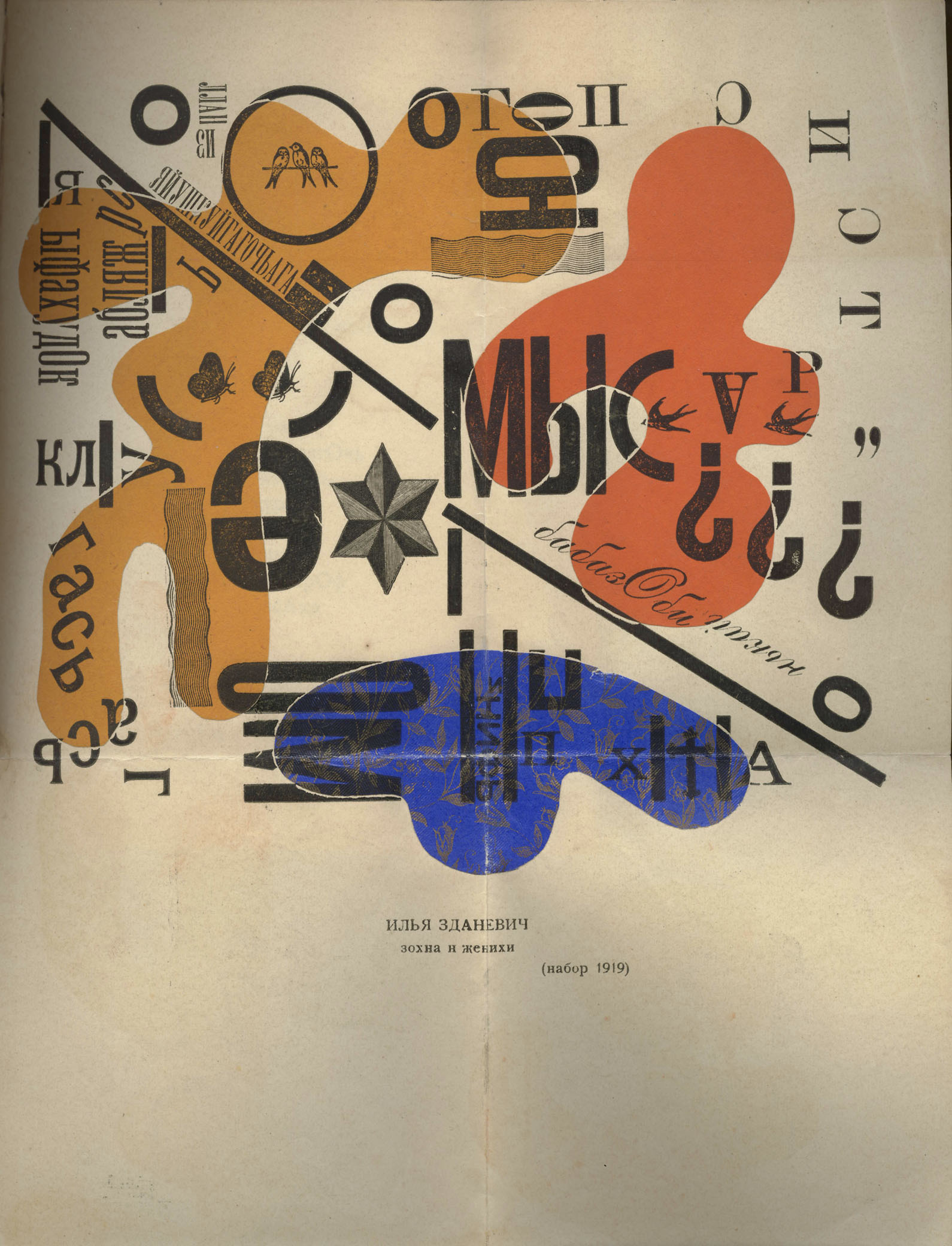

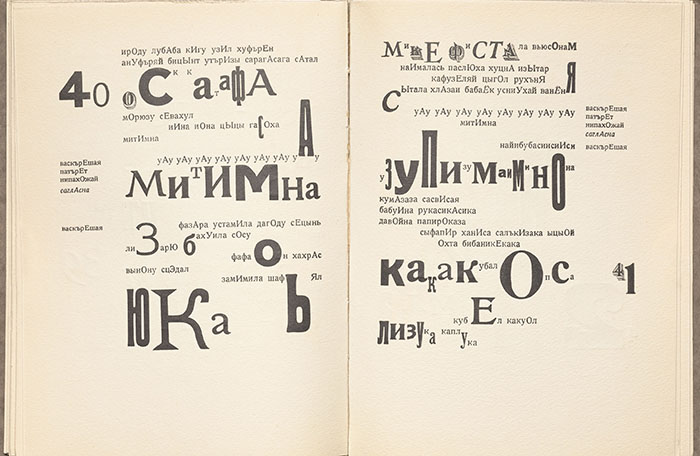

He dove into this milieu with great fervor. By the age of nineteen, he was an enfant terrible of Russian Futurism, on his way to becoming one of its best-known exponents. Together with other avant-garde poets, he participated in the development of the trans-rational literary language known as zaum, which abandoned “rational” expression, to convey meaning through sound, rhythm, and intonation. He began an audacious series of experiments in dramatic writing that involved short performances called dras.

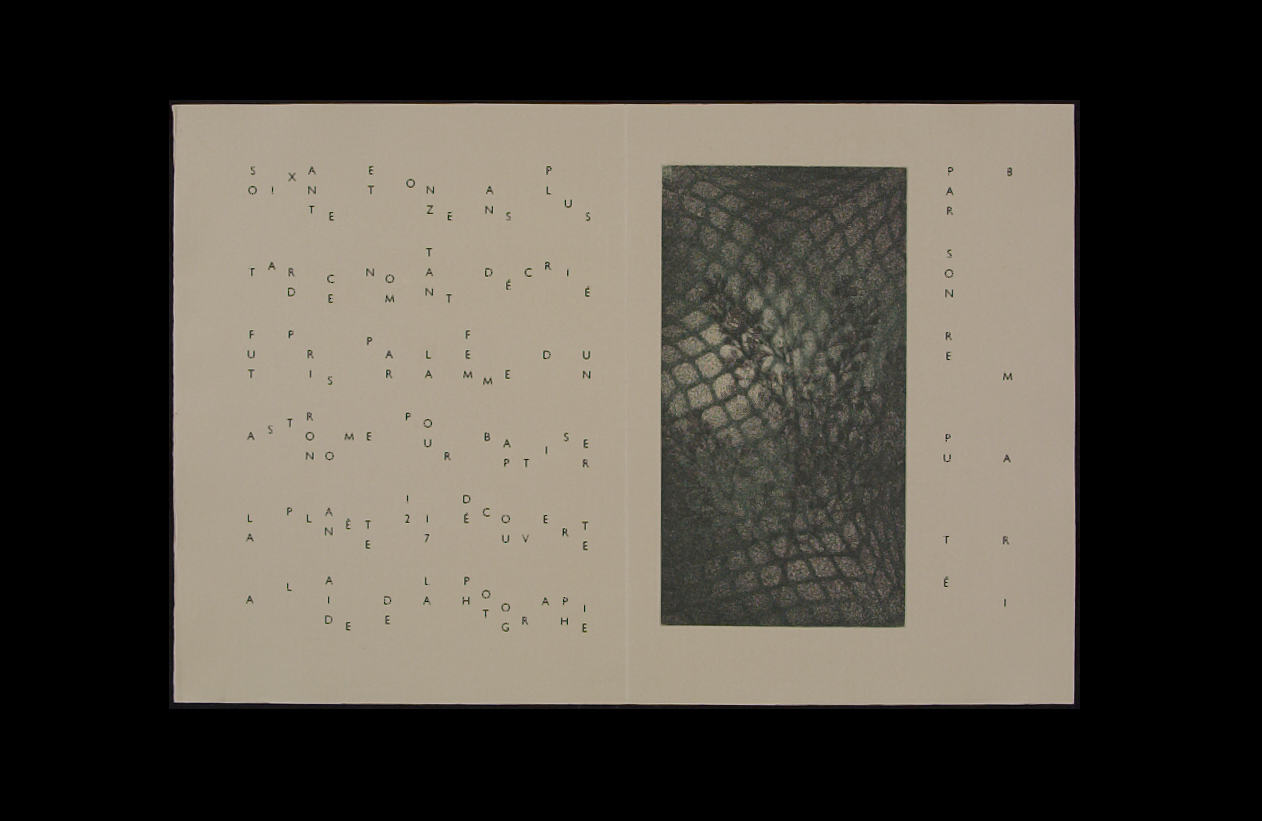

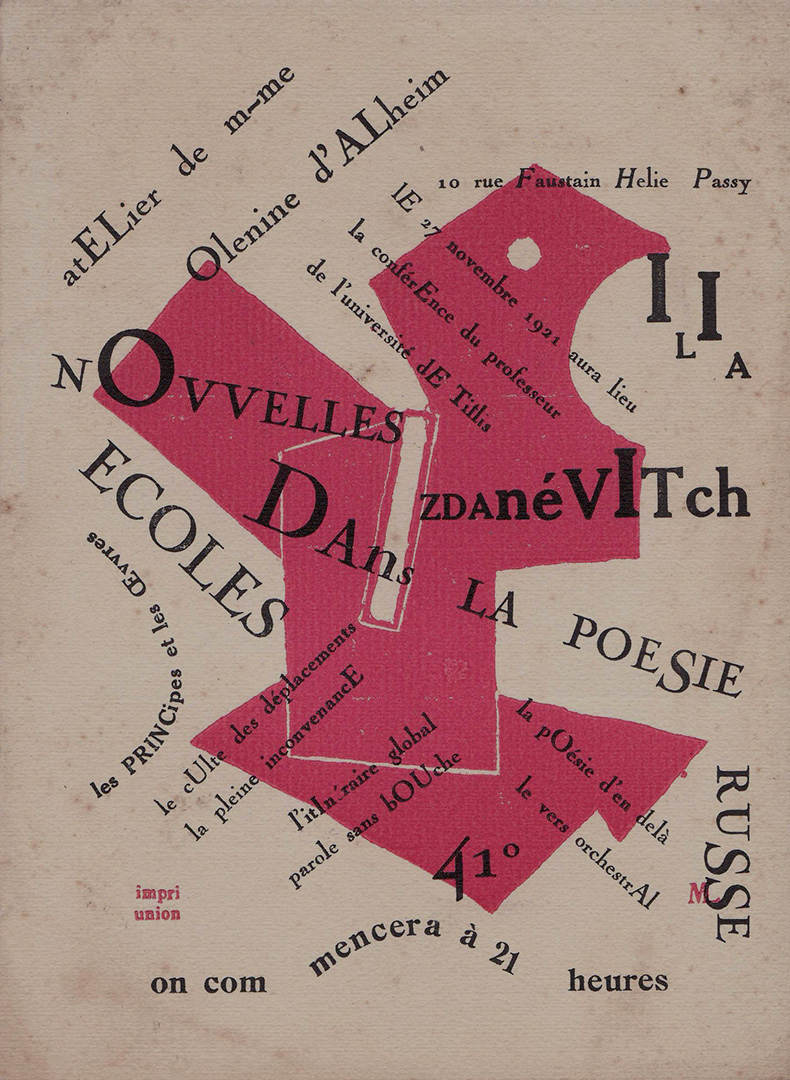

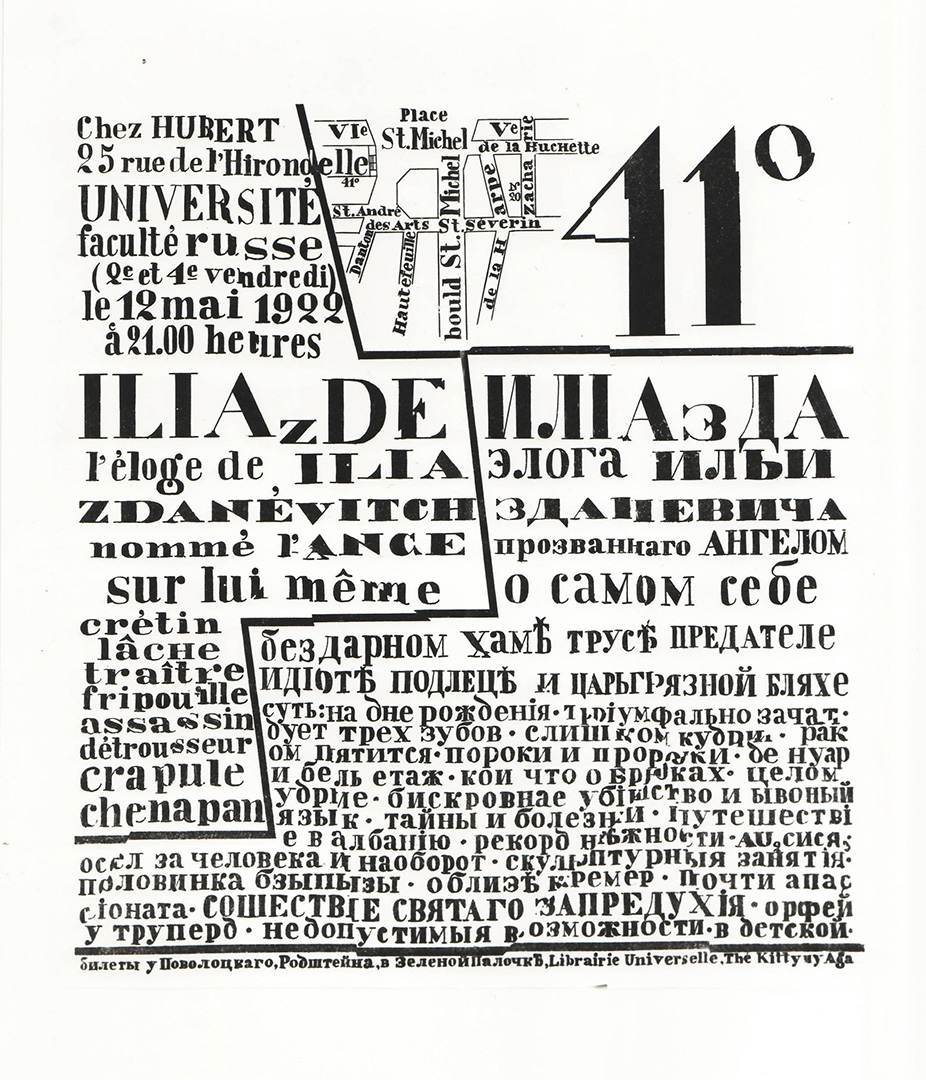

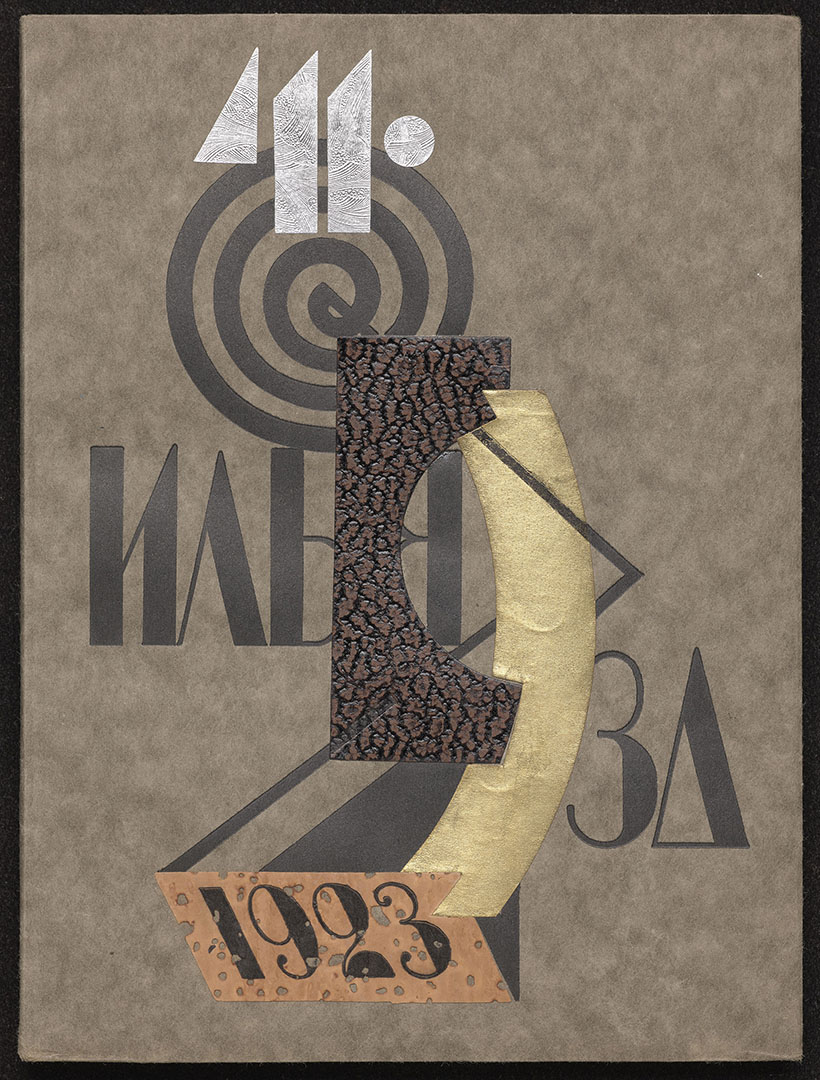

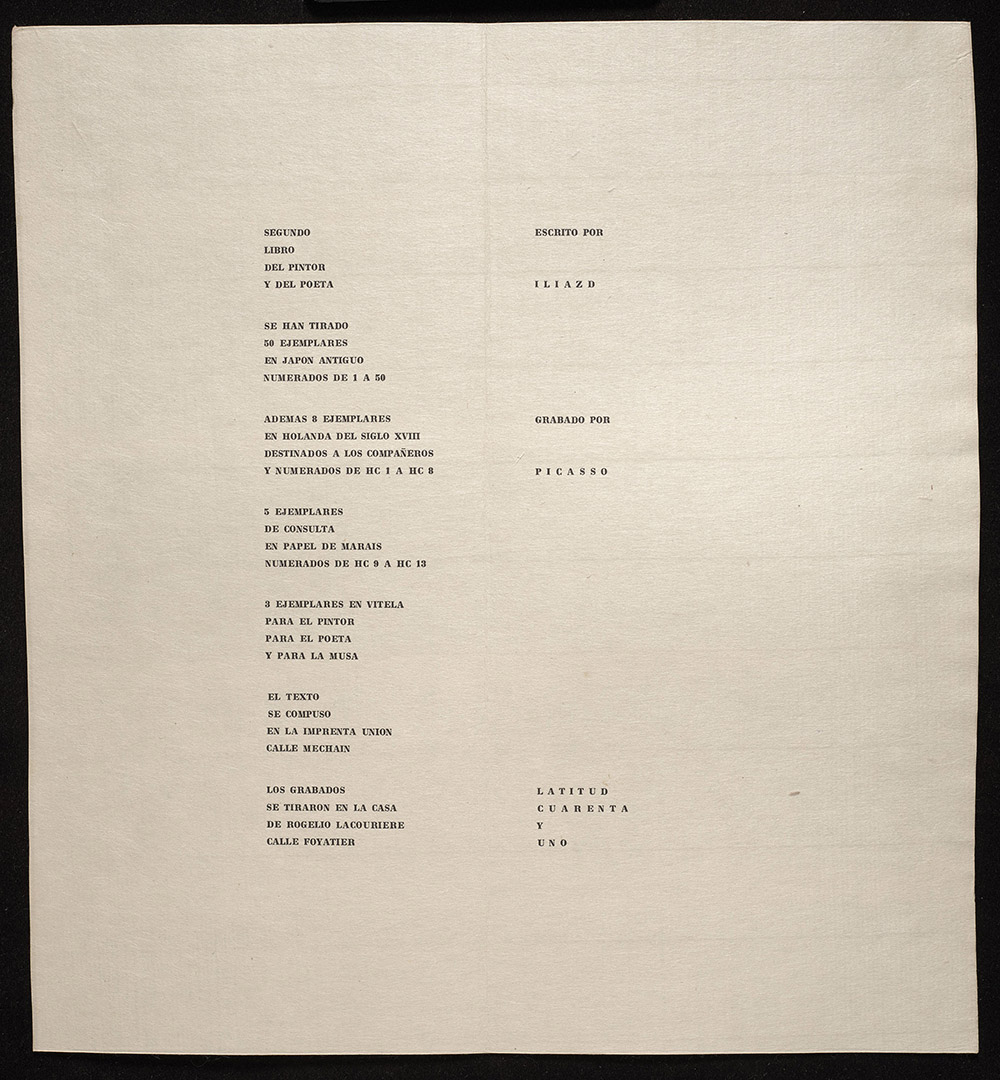

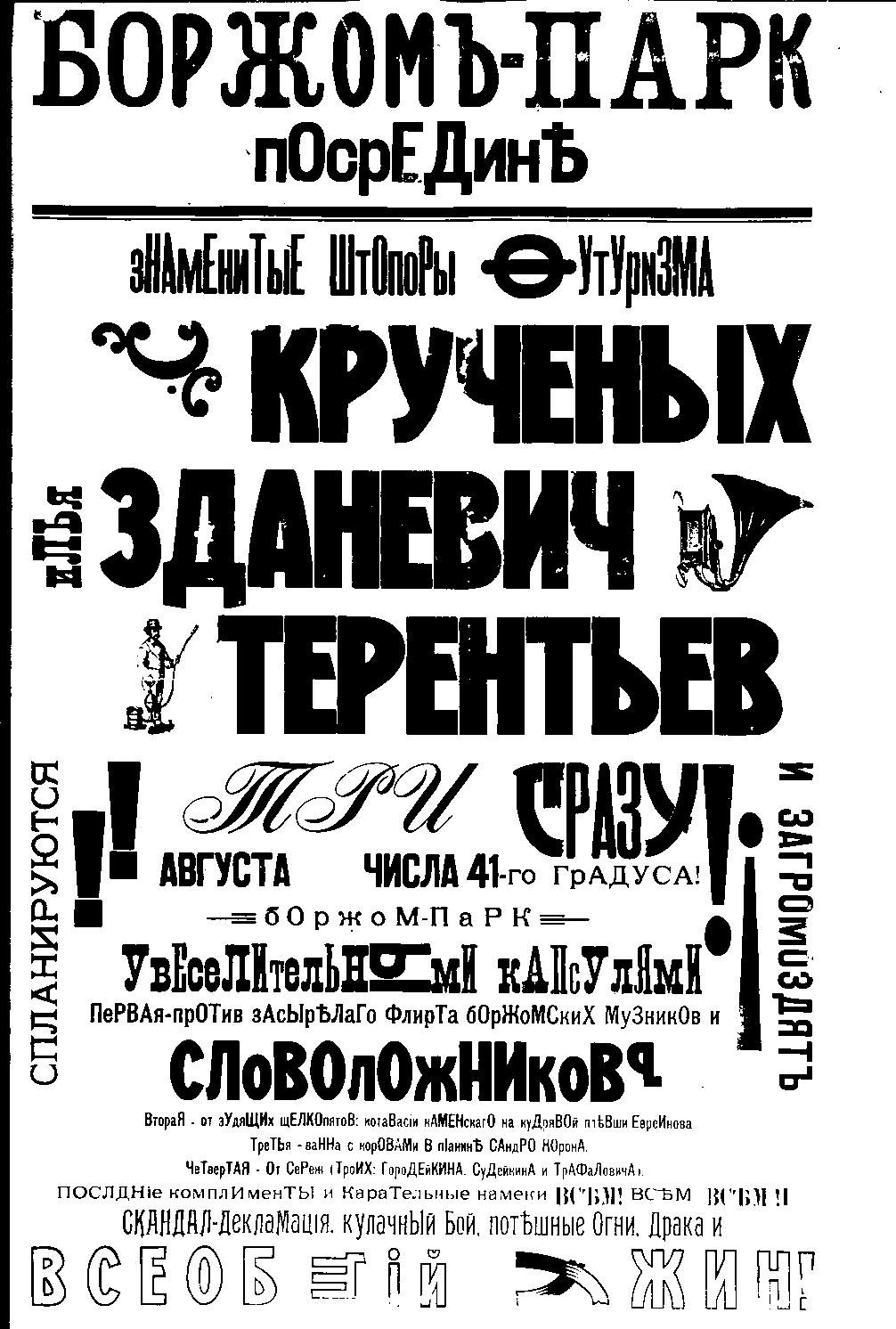

By age twenty-three, Ilia was back in Tiflis as the leader of a group that established the city as a center of Futurist art and poetry. In 1918 the group christened itself the University of the 41º, whose name they said denoted the latitude of Tiflis, the alcoholic content of Georgian brandy, and the temperature in centigrade at which fever leads to delirium. Iliazd apprenticed at a Tiflis print shop to learn typesetting and typography. His talent as a designer blossomed, and he began to experiment with visual poetry. He co-founded what would be his lifelong publishing imprint, 41 Degrees.

His group unabashedly stated that its goal was “to change the axis of the earth.” As this ambition suggests, Ilia Zdanevich was ready to perform on a larger stage. He adopted a new identity and a new name: Iliazd.

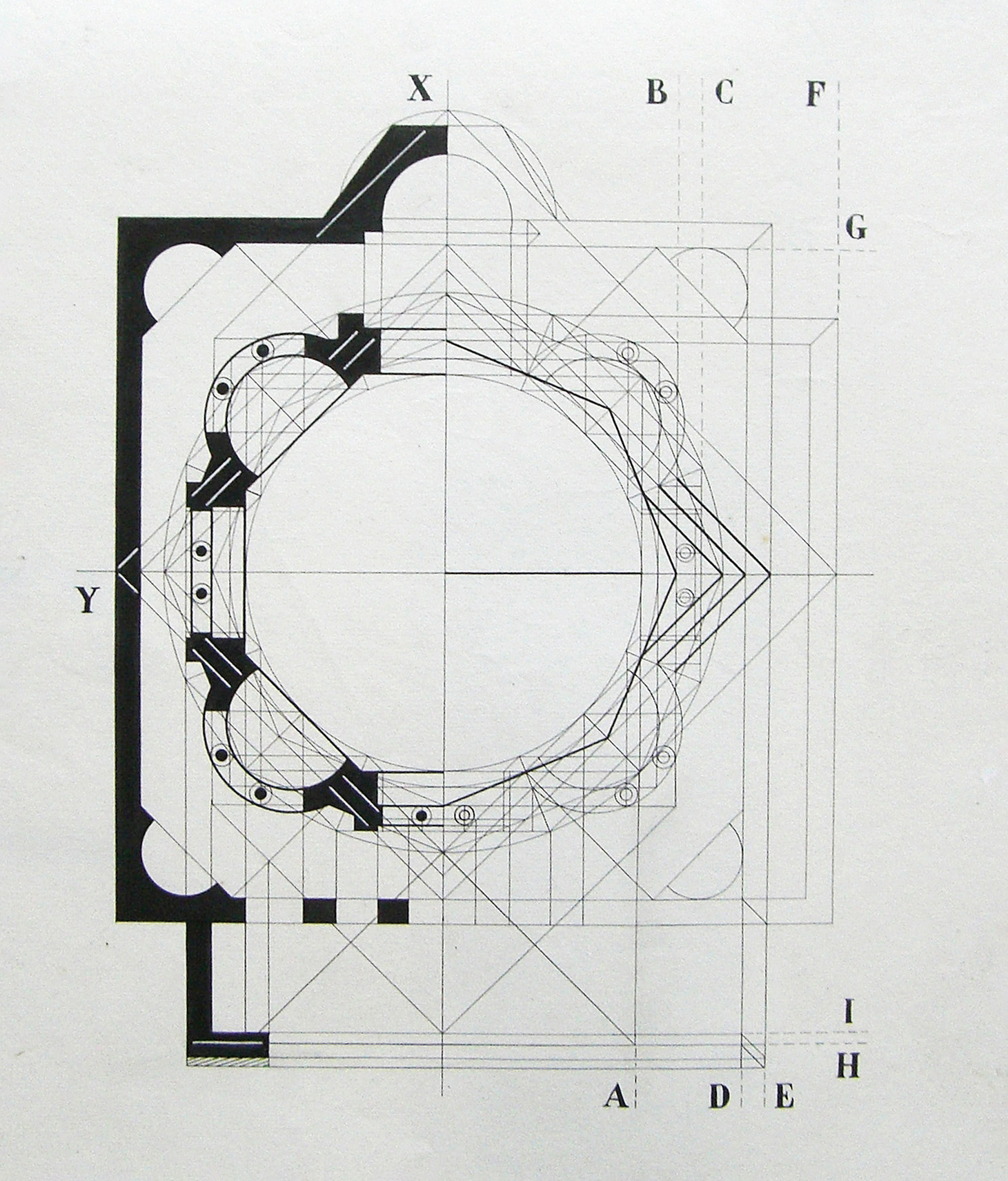

Constantinople

As the center of the European avant-garde, Paris was a magnet for young artists and writers from throughout the continent. However, it wasn’t always easy to get there. Iliazd’s wait for a visa required a lengthy stay in Constantinople. During his time there he made an intensive study of Byzantine churches, including the Hagia Sophia. His renderings of Byzantine architecture found widespread acclaim from scholars in the field, and he continued to be a recognized figure in Byzantine studies until well into the 1960s.

First Book in Paris

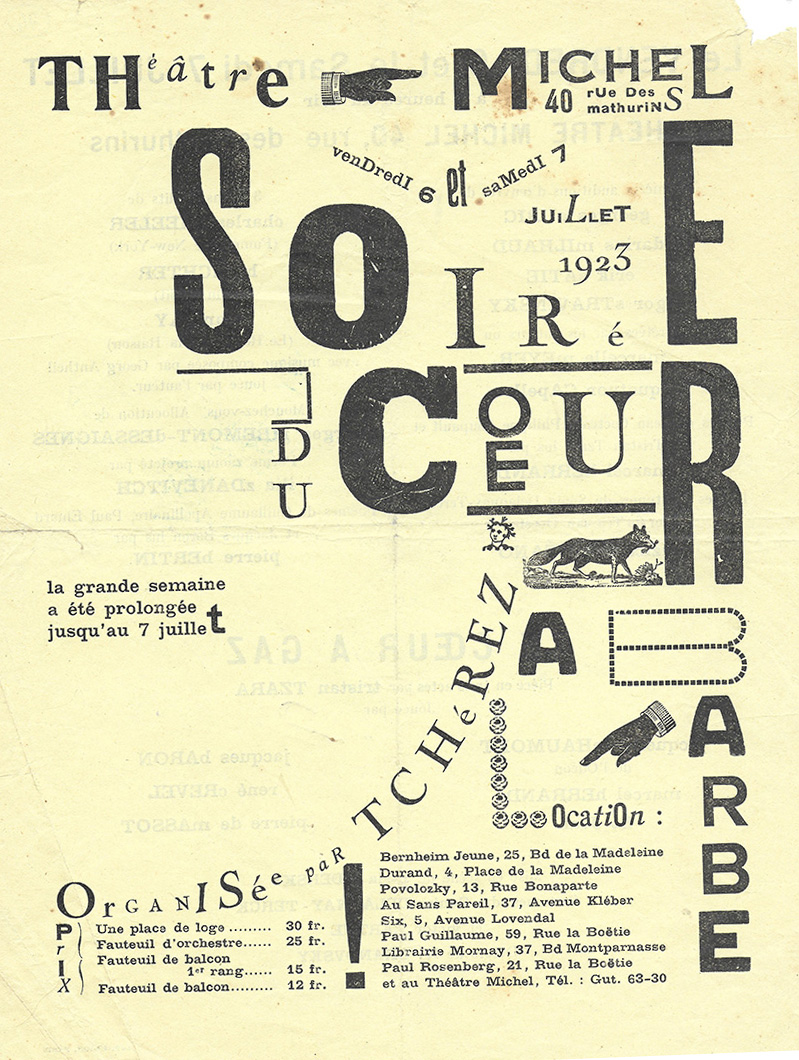

In 1923 Iliazd published the last in a cycle of five dramatic writings, or dras, the first four of which had been published in Tiflis. The publication, LidantYU fAram (Ledentu as Beacon; see ahead Chapter IV), created during his time in Turkey, was his first artist’s book published in Paris. He called it his farewell to Futurism. Although he did not publish another artist’s book until 1940, in 1930 he self-published a phantasmagorical adventure novel, Rapture. The book received little notice at the time, but Columbia University Press has recently republished it in an English translation by Thomas Kitson.

Early Career and Marriage

To earn a living in Paris, Iliazd apprenticed in the couture shop of the artist and fashion designer Sonia Delaunay, and when the Soviet embassy opened in Paris in 1925, he worked there for a time as an interpreter. In 1926 he began designing fabrics for Coco Chanel, and the following year he married a fashion model, Simone-Axele Brocard, with whom he had two children. He rose through the ranks at Chanel, becoming a lead designer and then director of a textile factory, inventing a mechanized loom that remained in operation for decades. Though he left her employ in 1933, he and Chanel remained personal friends.

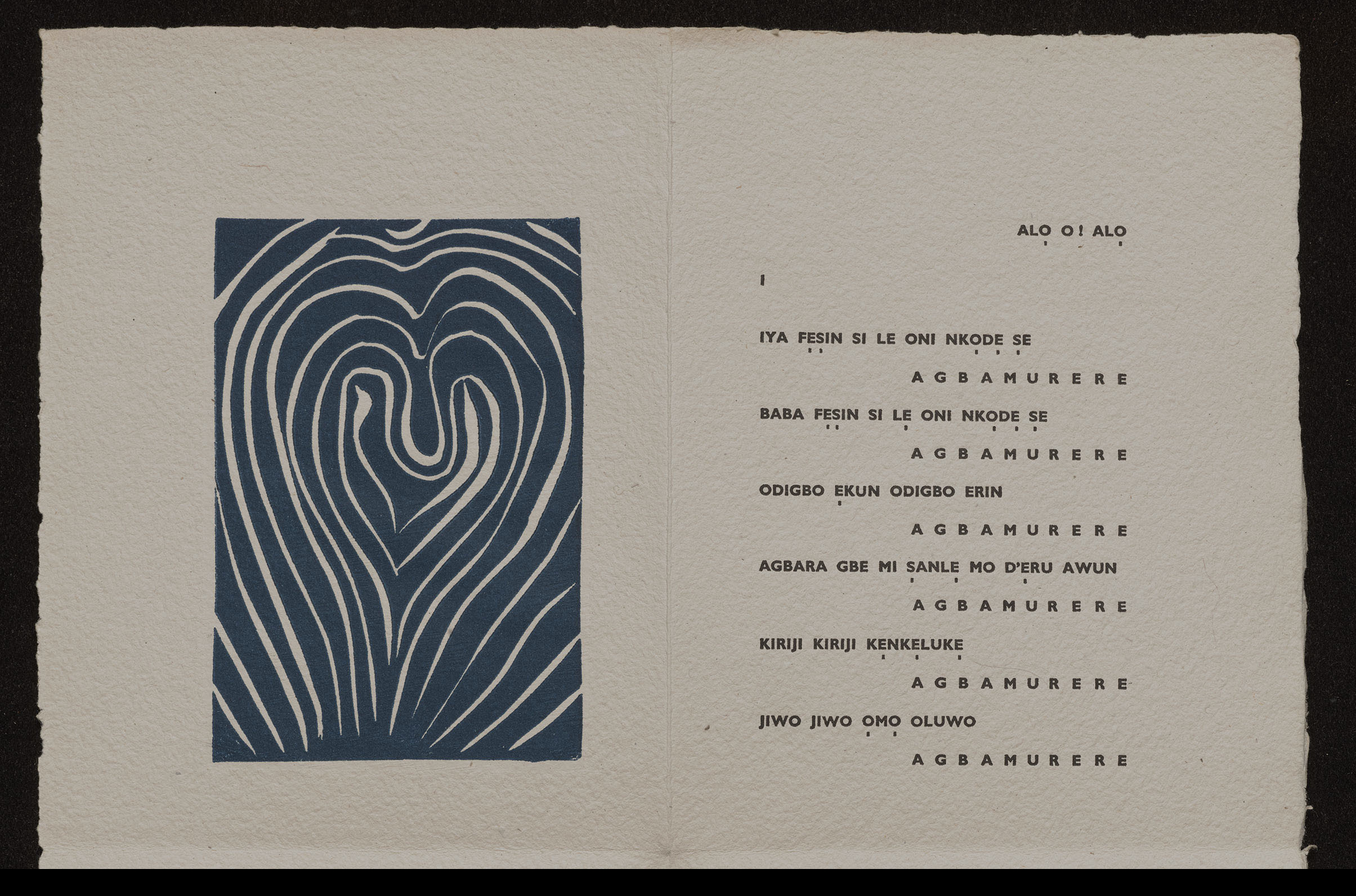

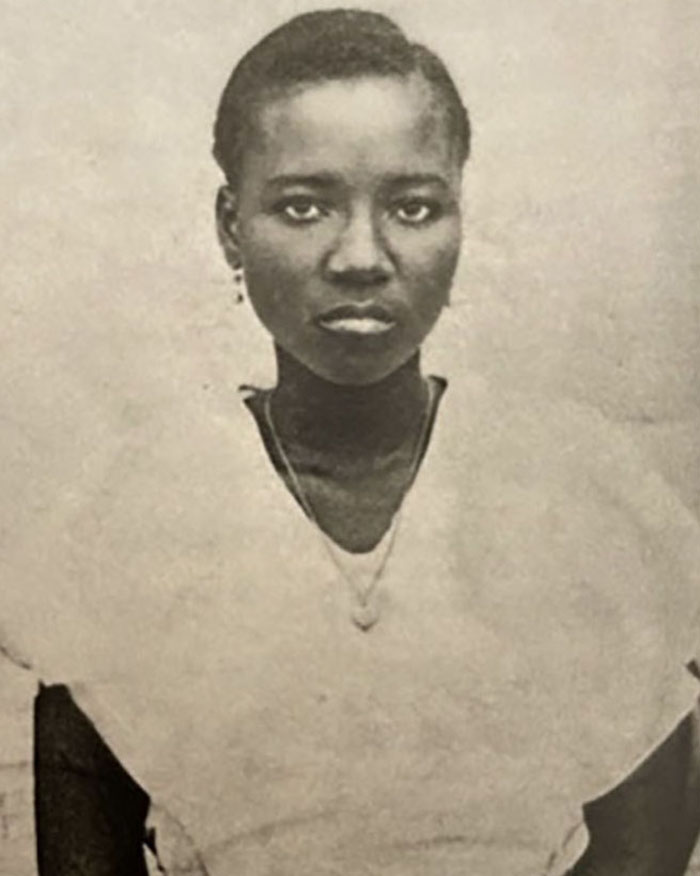

Ibironke

Iliazd’s marriage to Brocard ended in 1935. In 1943 he met Ibironke Akinsemoyin, a young Nigerian woman of royal lineage, soon after she had been released from internment as a British subject by German occupation forces. They married after a short courtship, and a child was born to them late that year. It was fated to be a short marriage, ending in tragedy. Having contracted tuberculosis in the internment camp, Ibironke died in 1945.

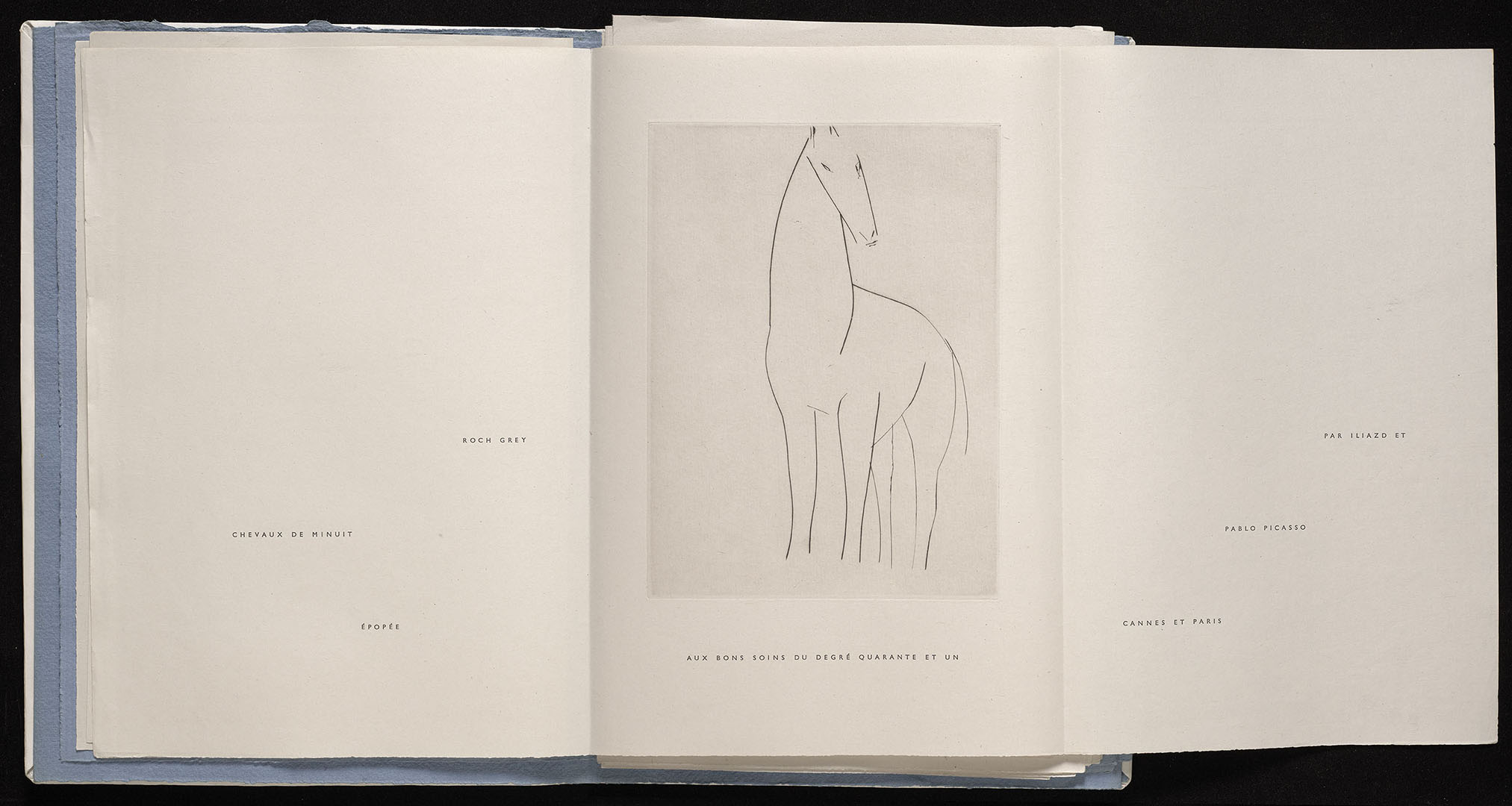

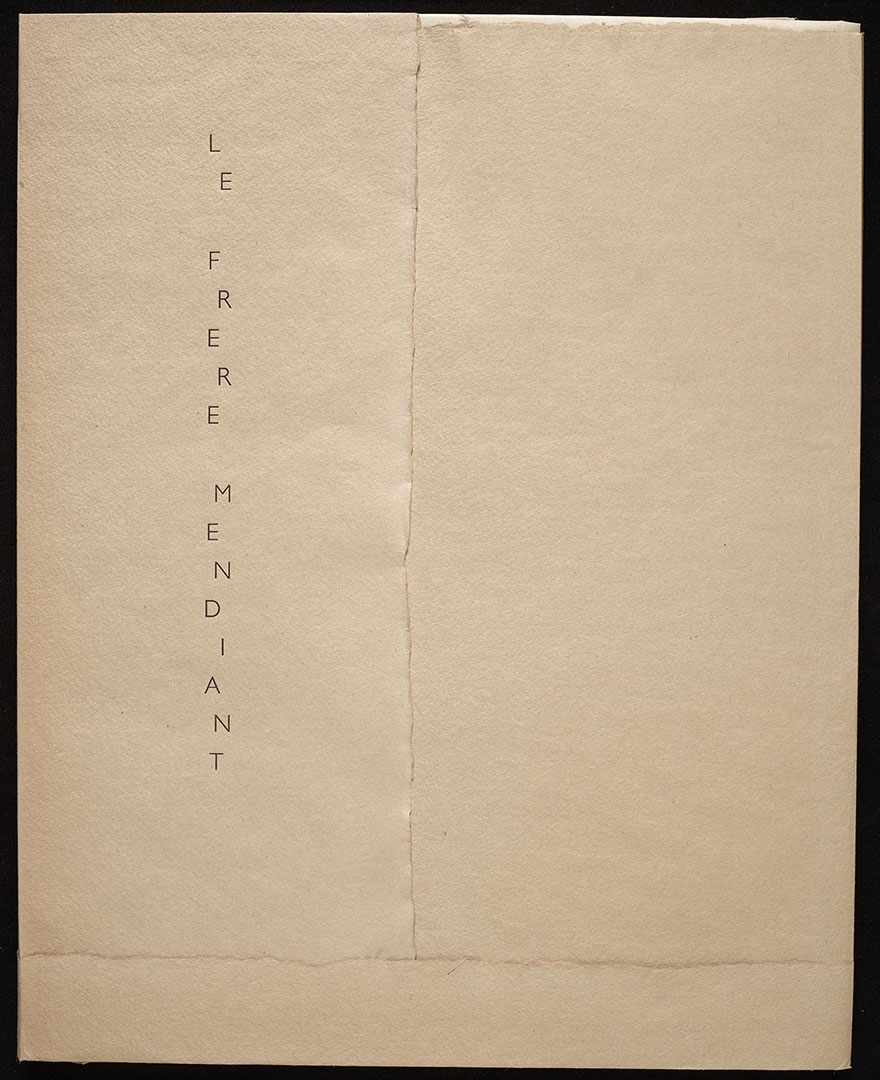

The relationship had kindled in Iliazd a deep sense of fellowship with the people of Africa, feelings that he expressed, in typical fashion, through obsessive research on the history of the continent and ultimately in the production of a collaborative artwork with Picasso, the book Le Frère mendiant, which appeared in 1959 (see ahead Chapter IV).

If the years 1935 to 1945 had been the most troubling and turbulent of Iliazd’s life, it was also a period that saw his rebirth as an artist and the blossoming of a close friendship and profound artistic partnership with Picasso.

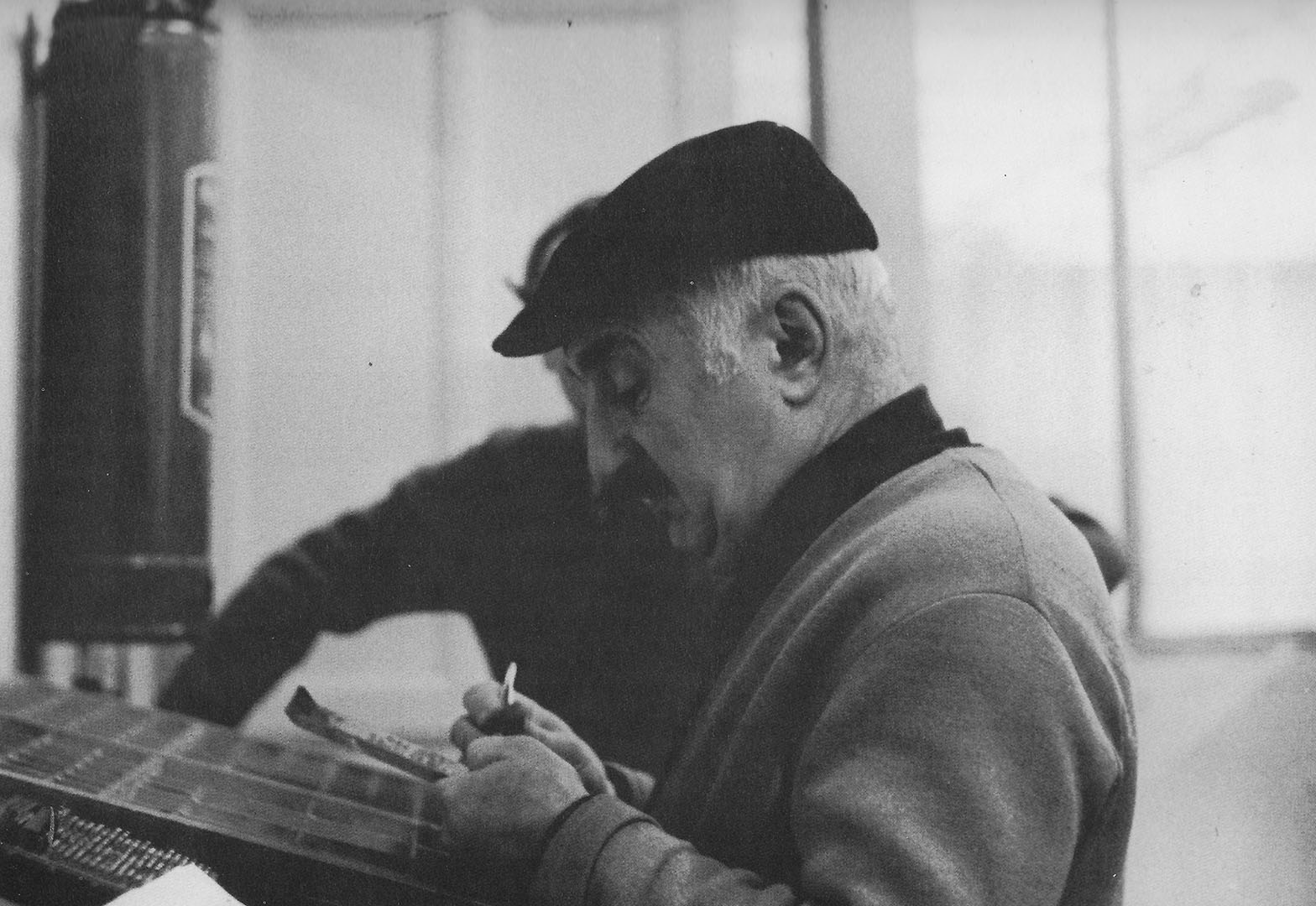

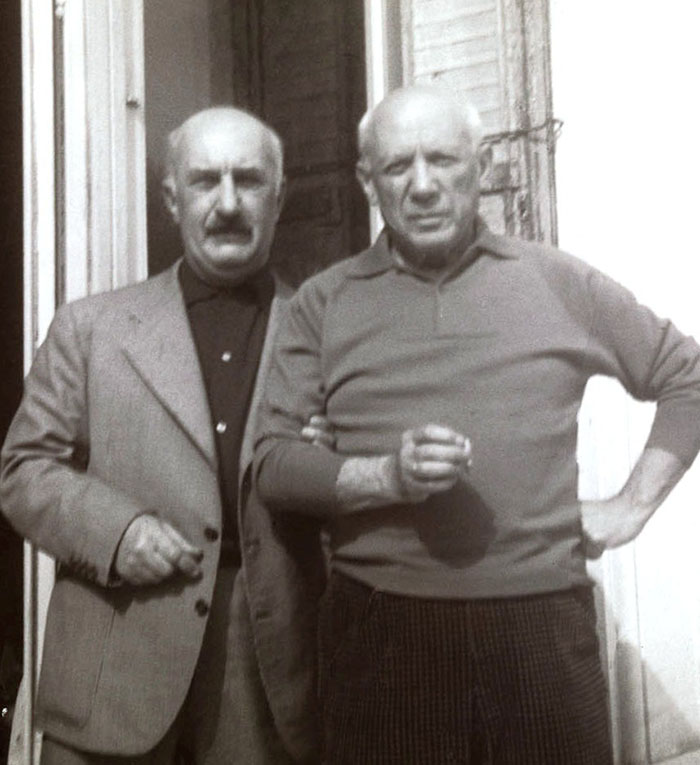

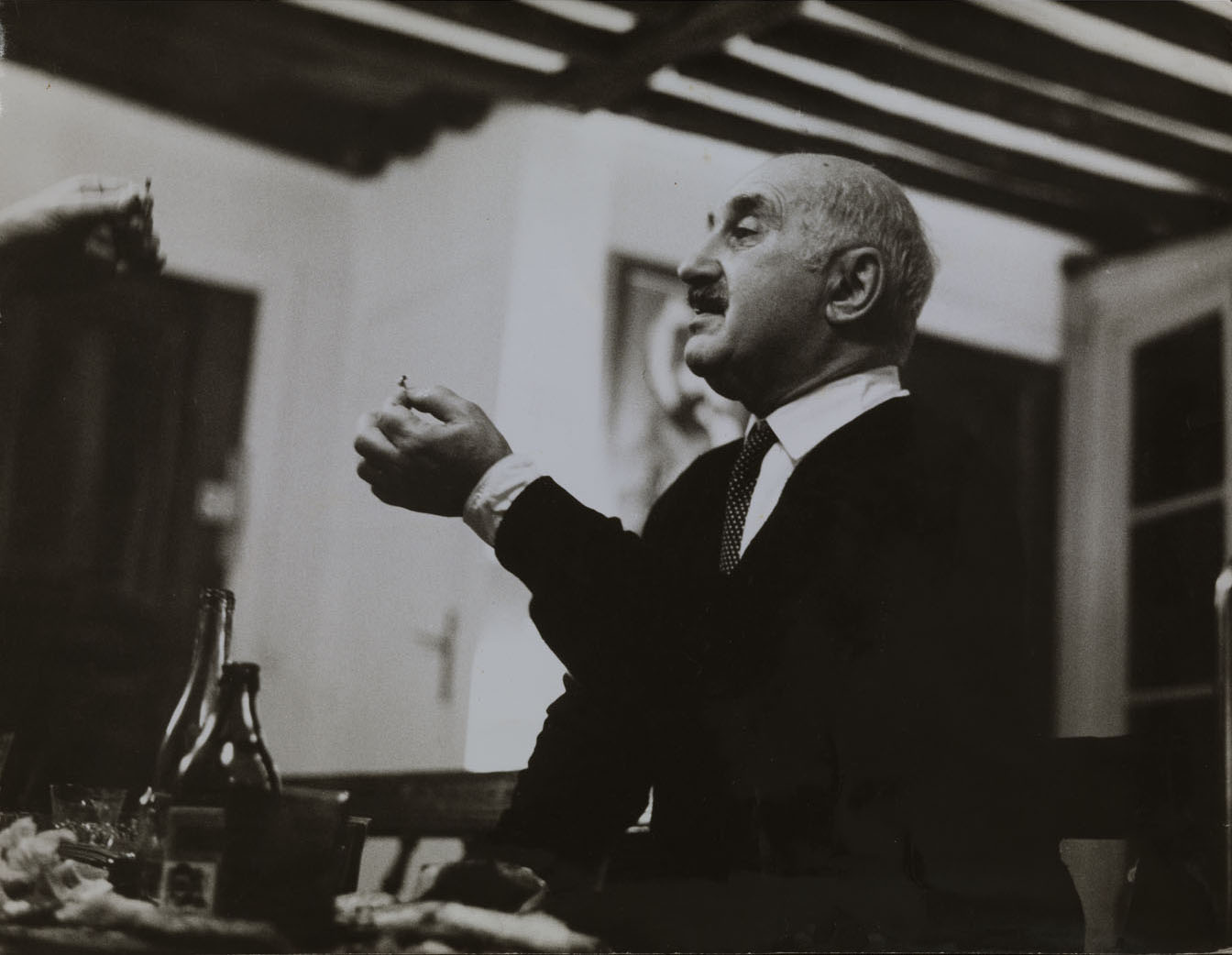

Picasso

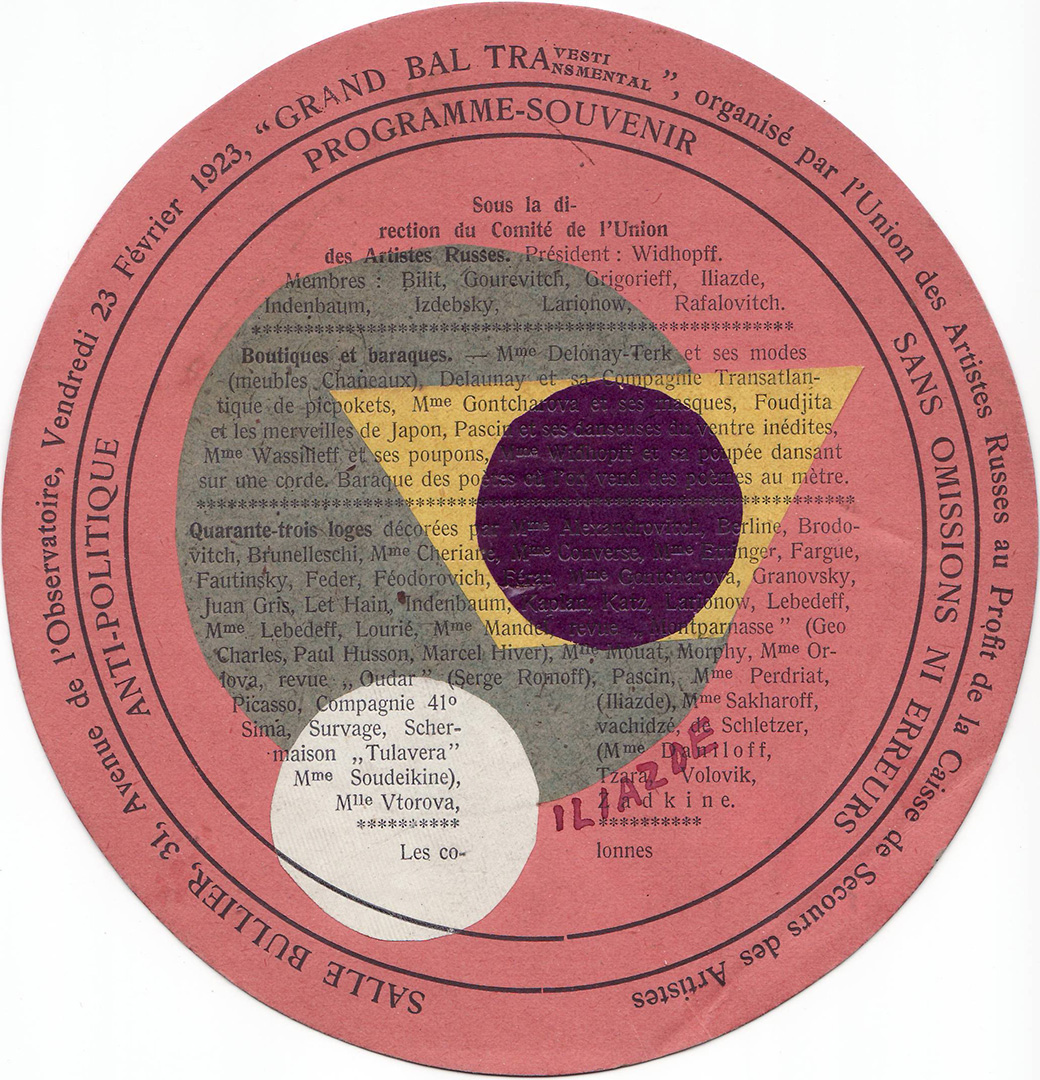

Iliazd and Pablo Picasso first met in 1922, when they served on the organizing committee of an artist’s ball. They stayed in occasional contact, and in the mid-1930s, after the breakup of his first marriage, Iliazd moved into a studio near Picasso’s. The two began to spend time together, meeting frequently during the time of the Spanish Civil War. Iliazd saw Picasso paint Guernica, the artist’s 1937 work created in response to the German Luftwaffe’s bombing of the eponymous Basque town.

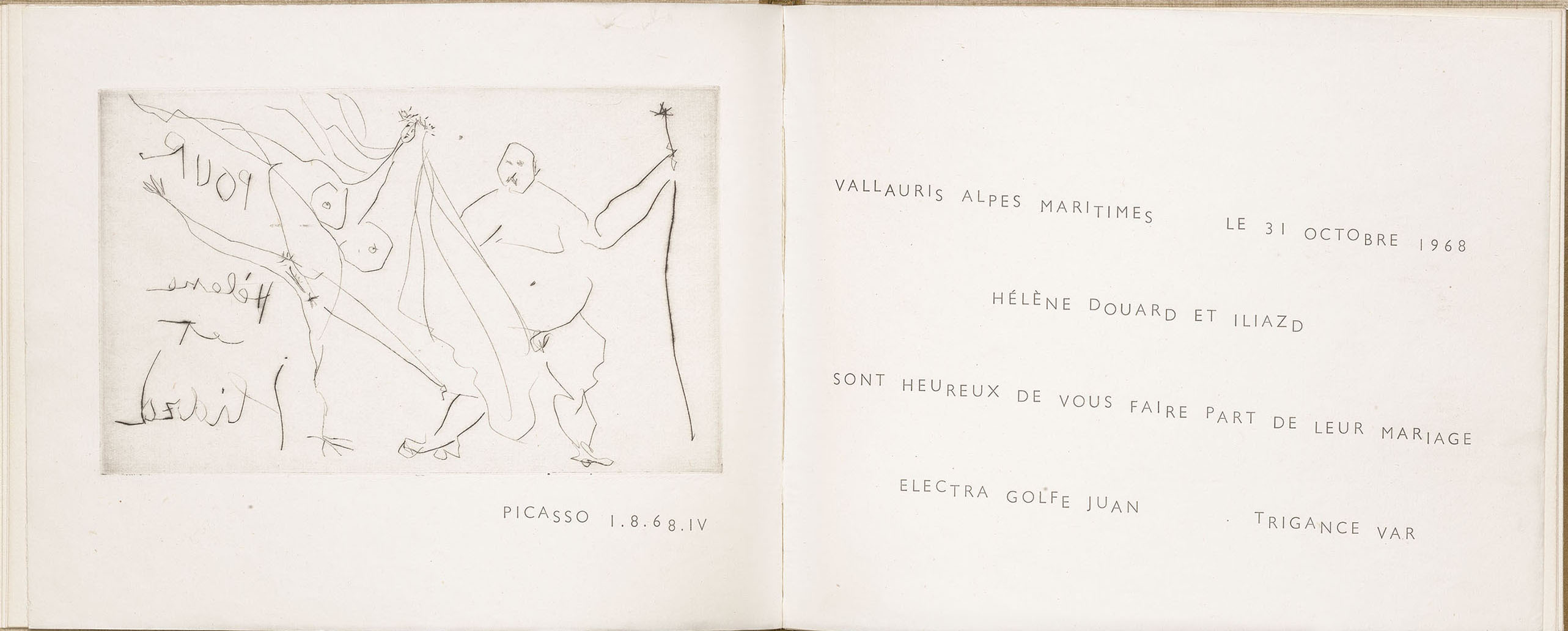

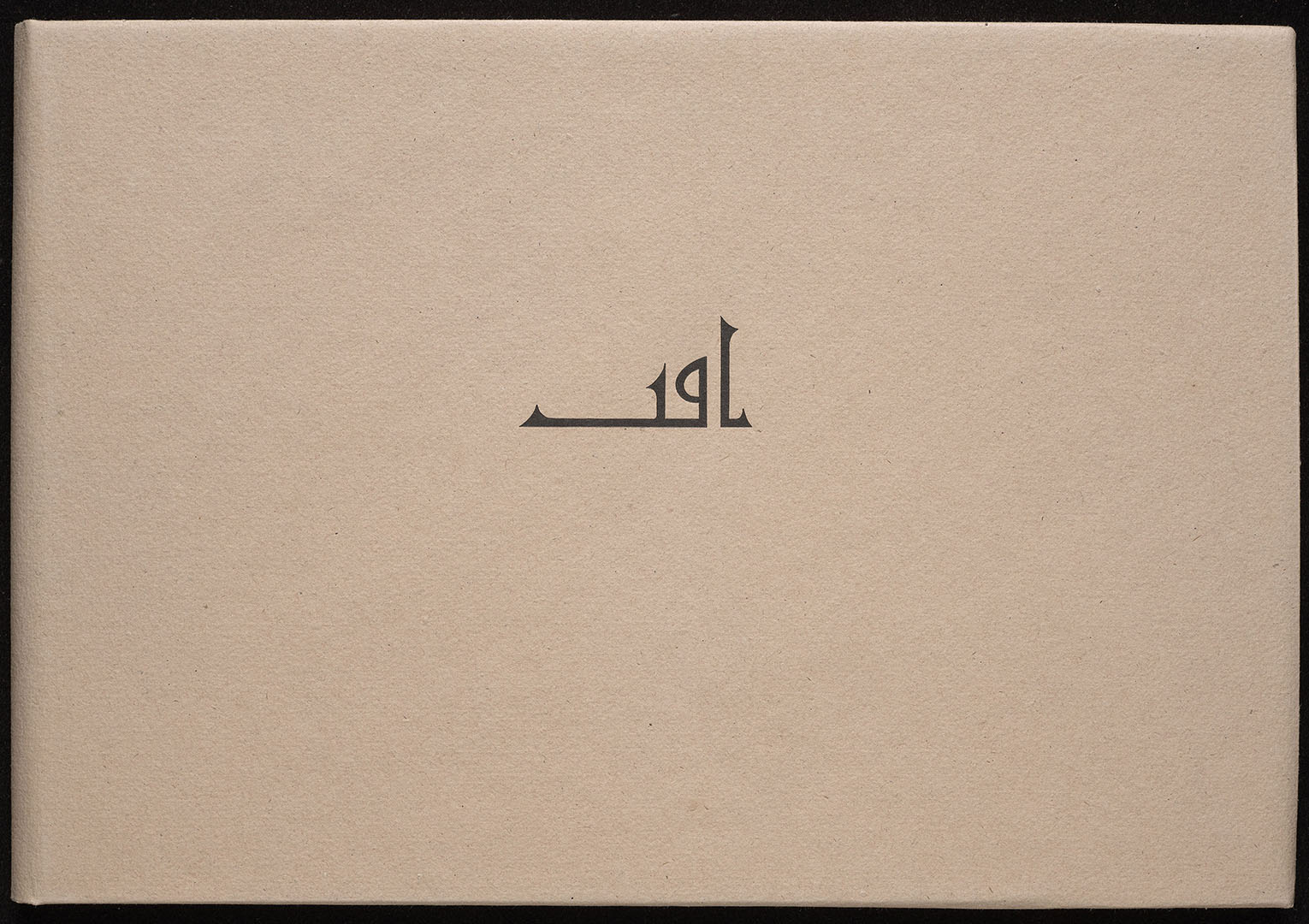

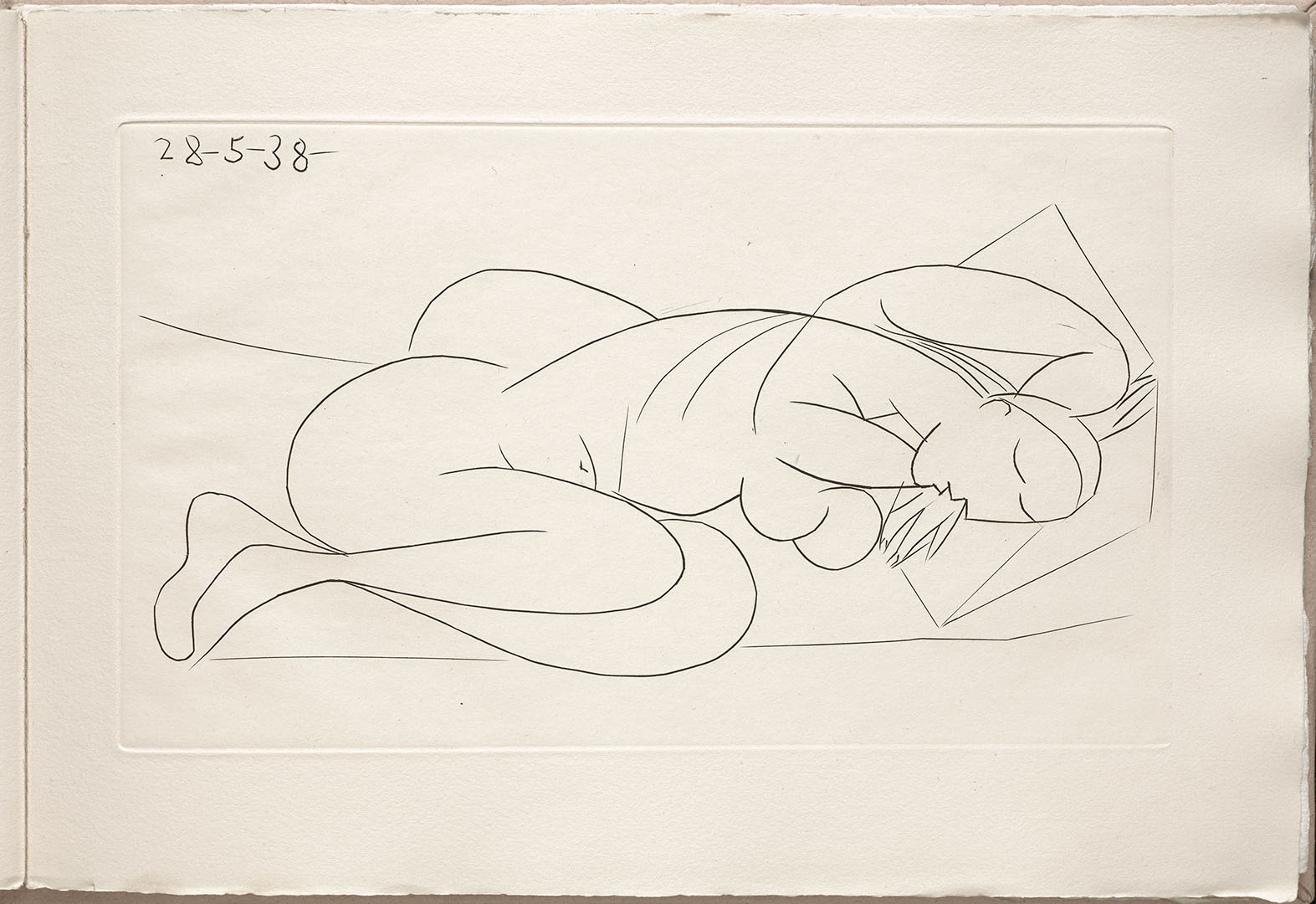

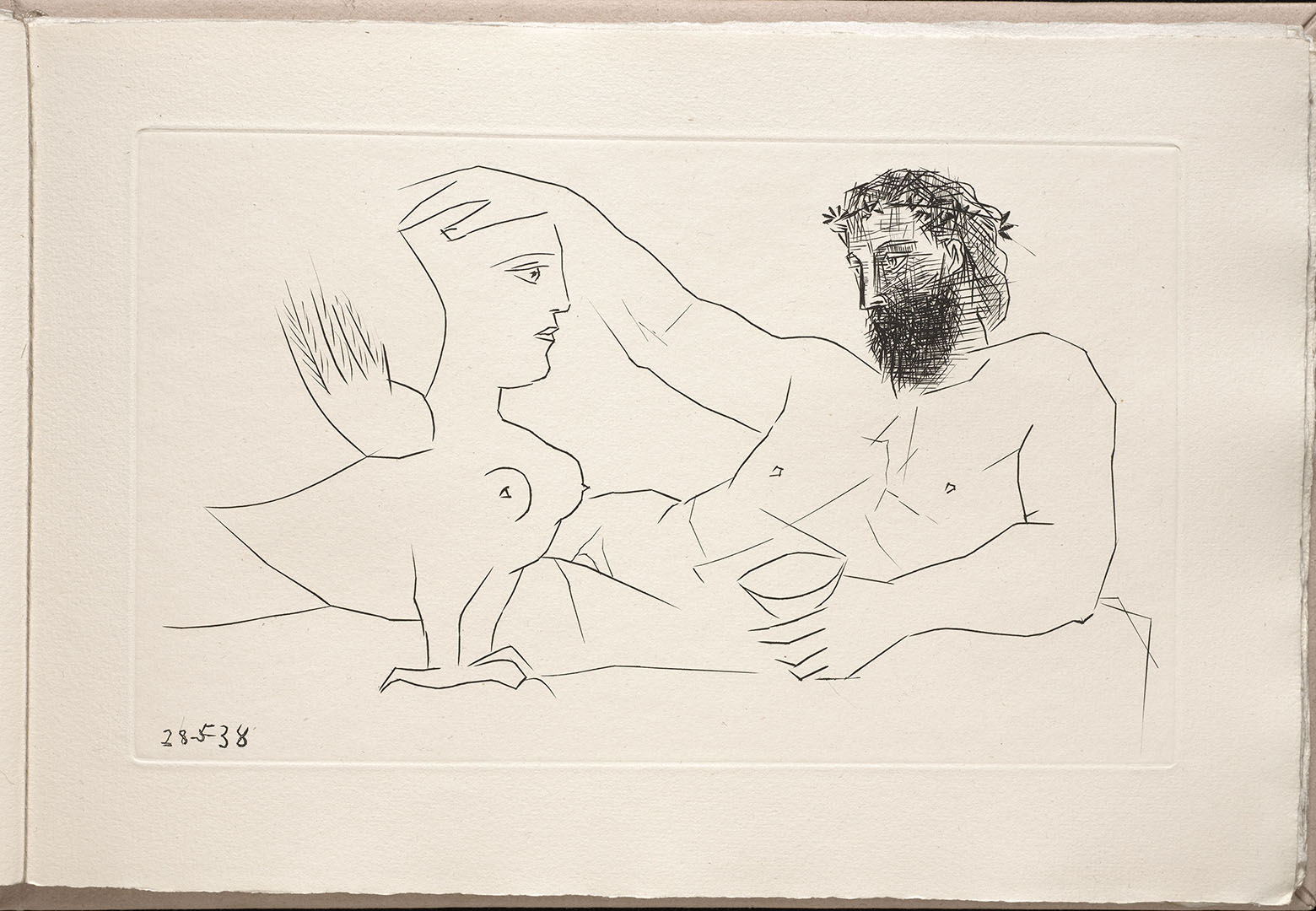

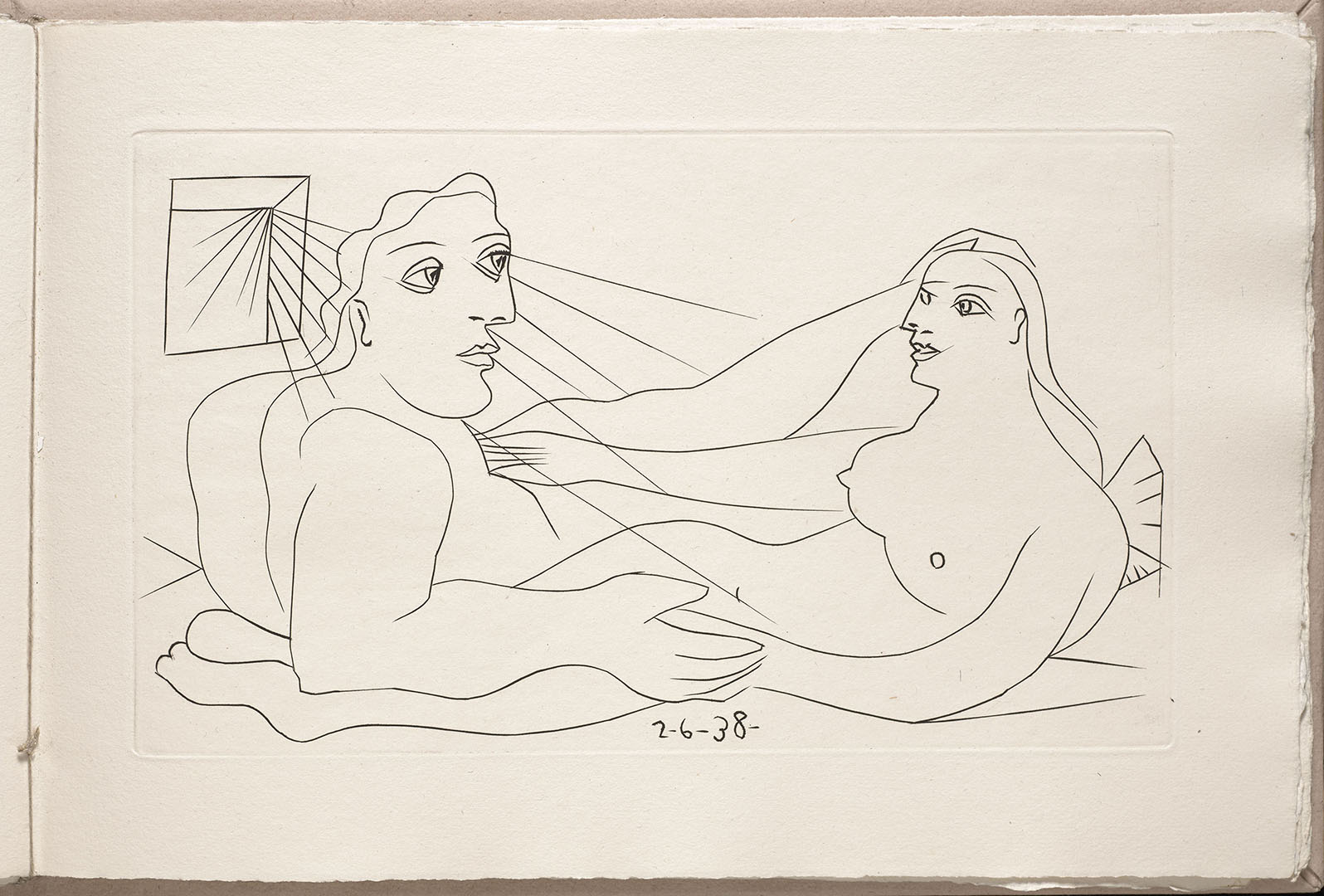

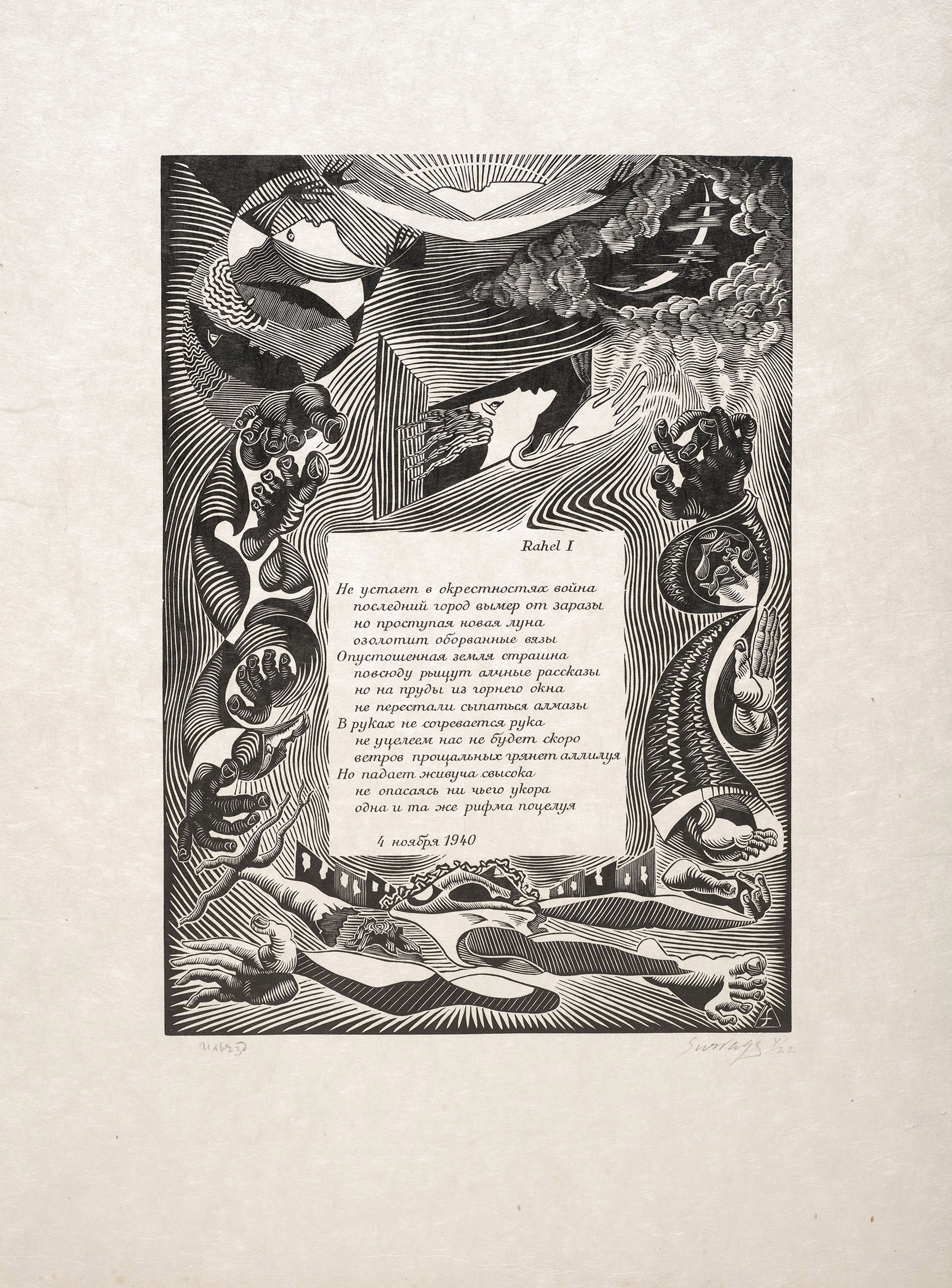

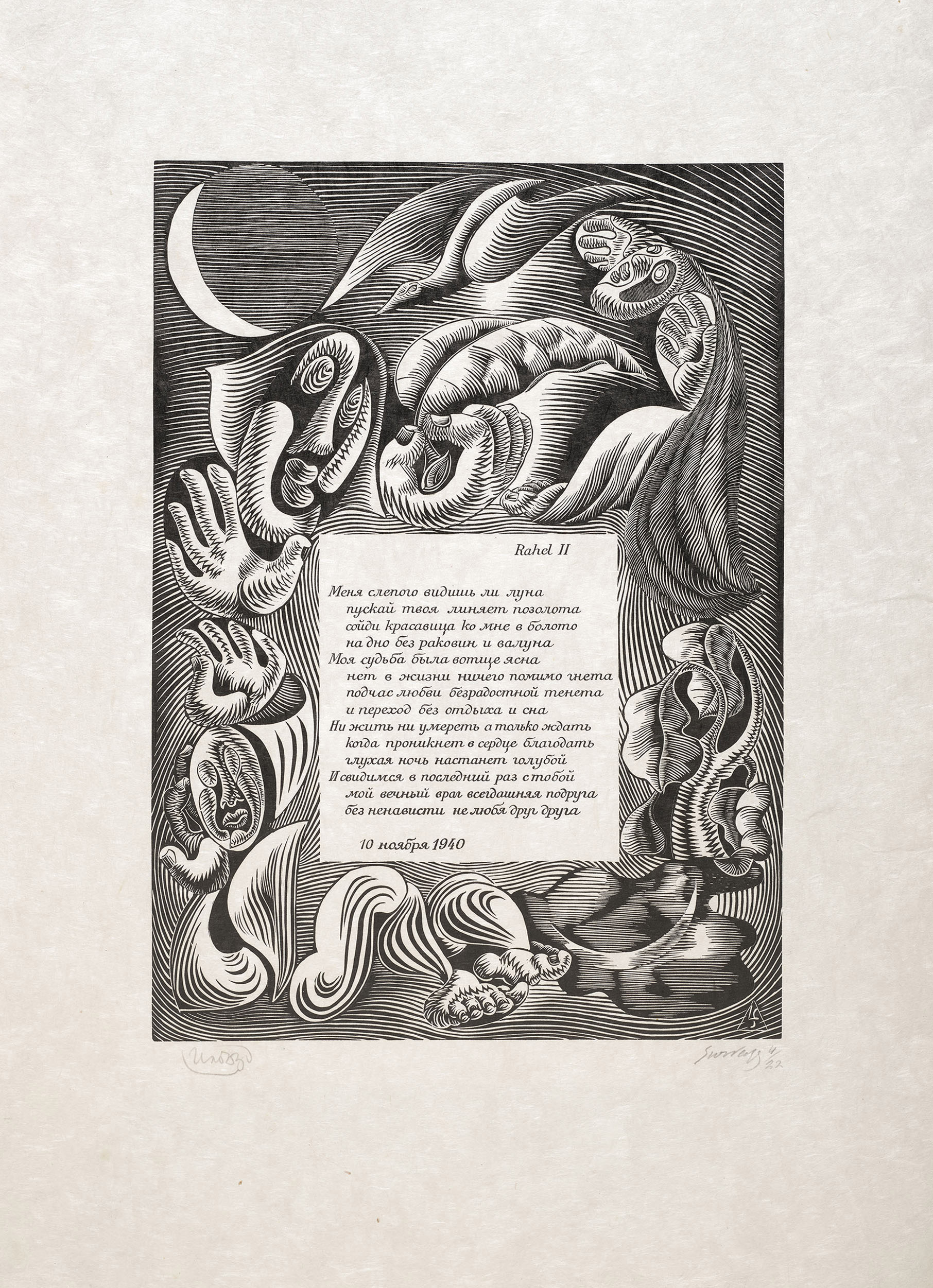

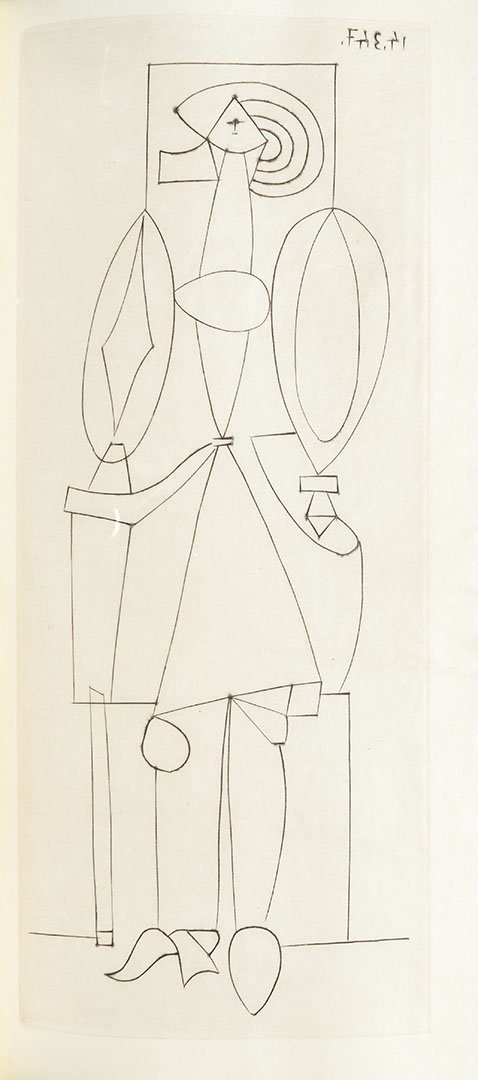

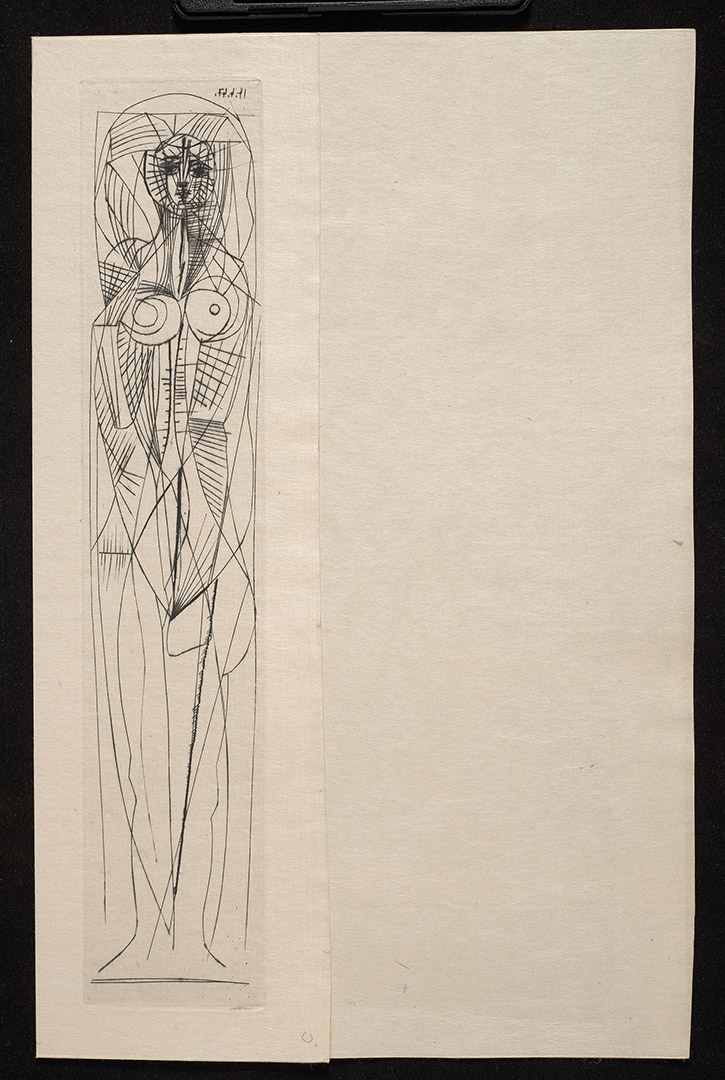

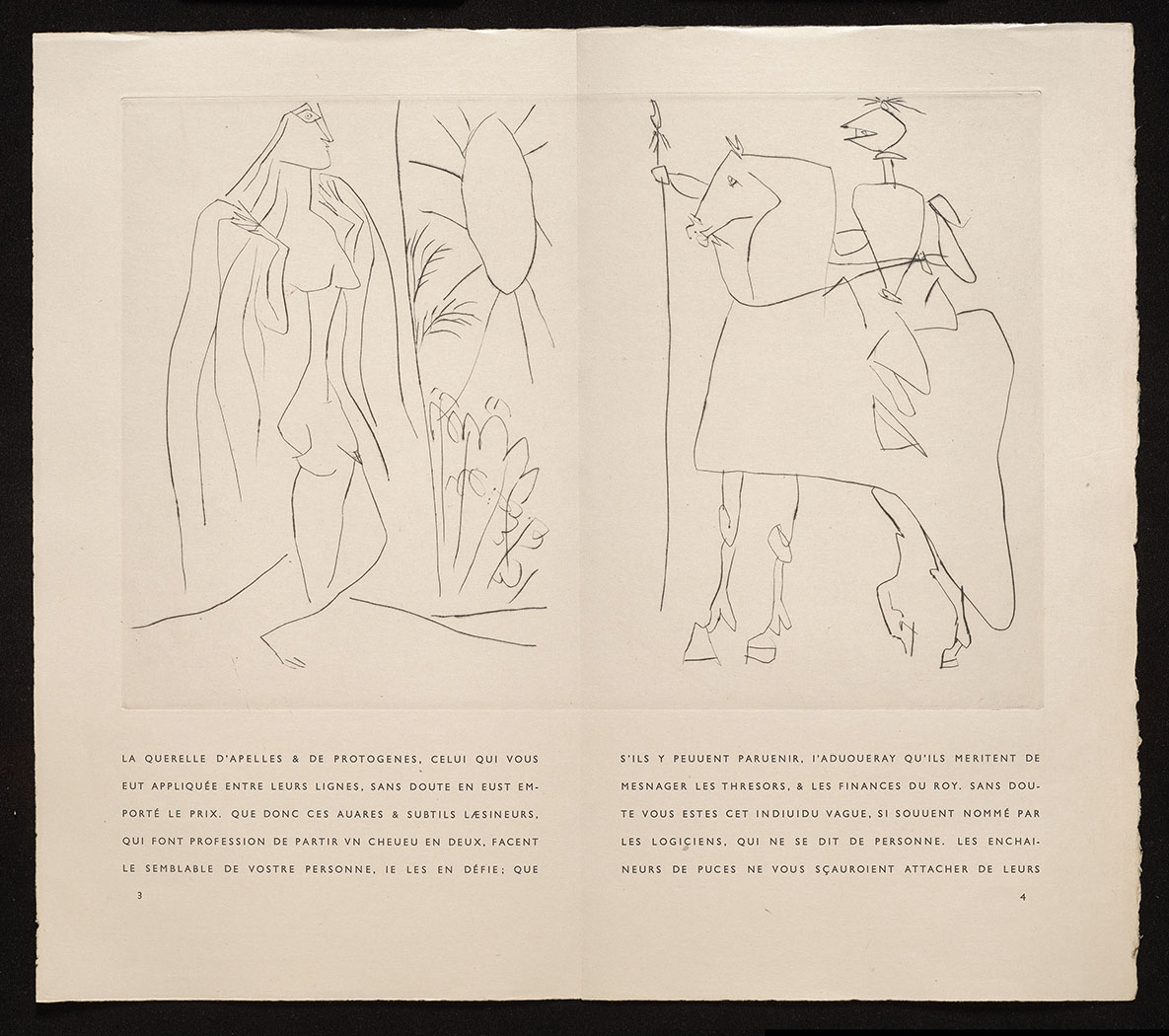

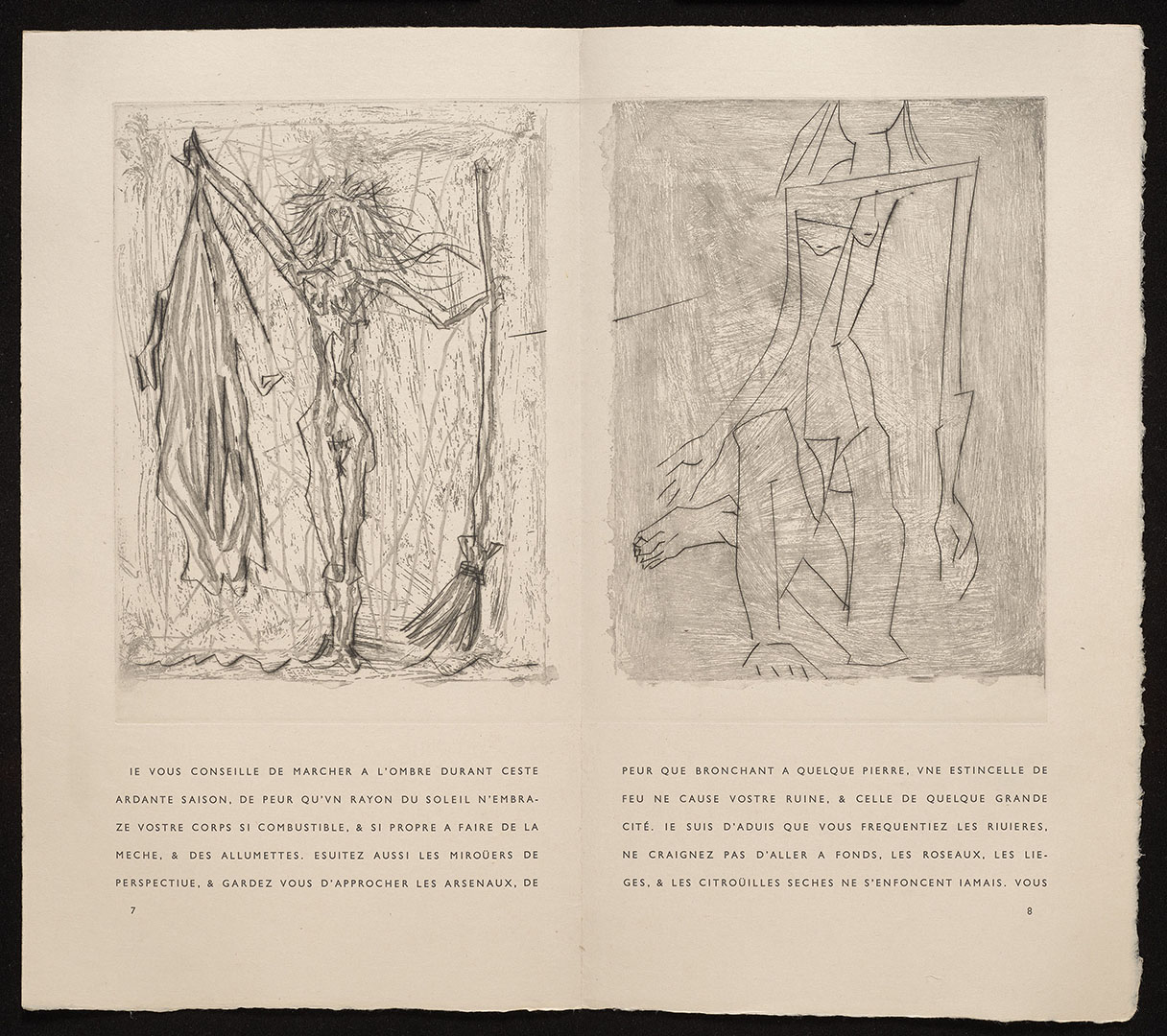

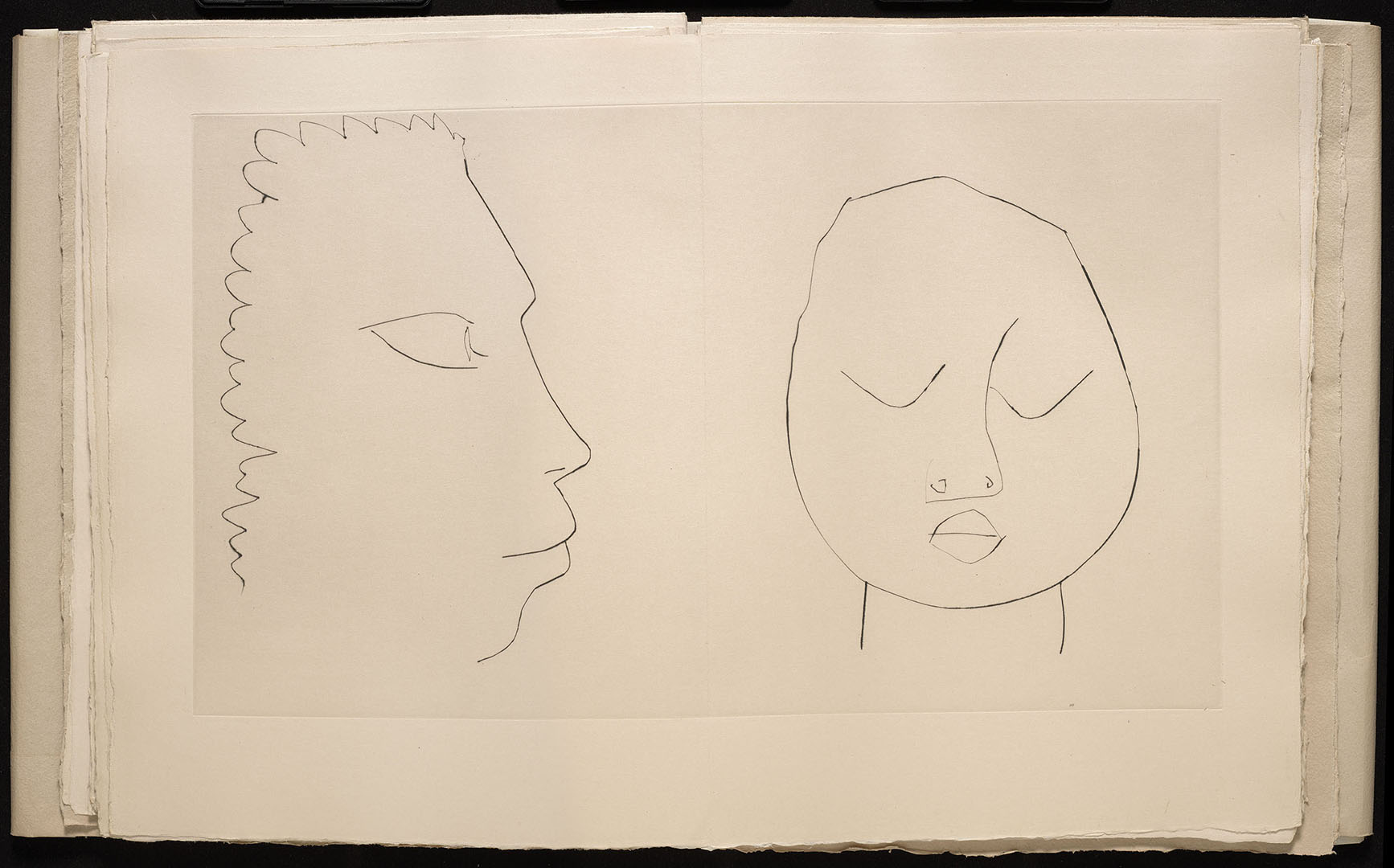

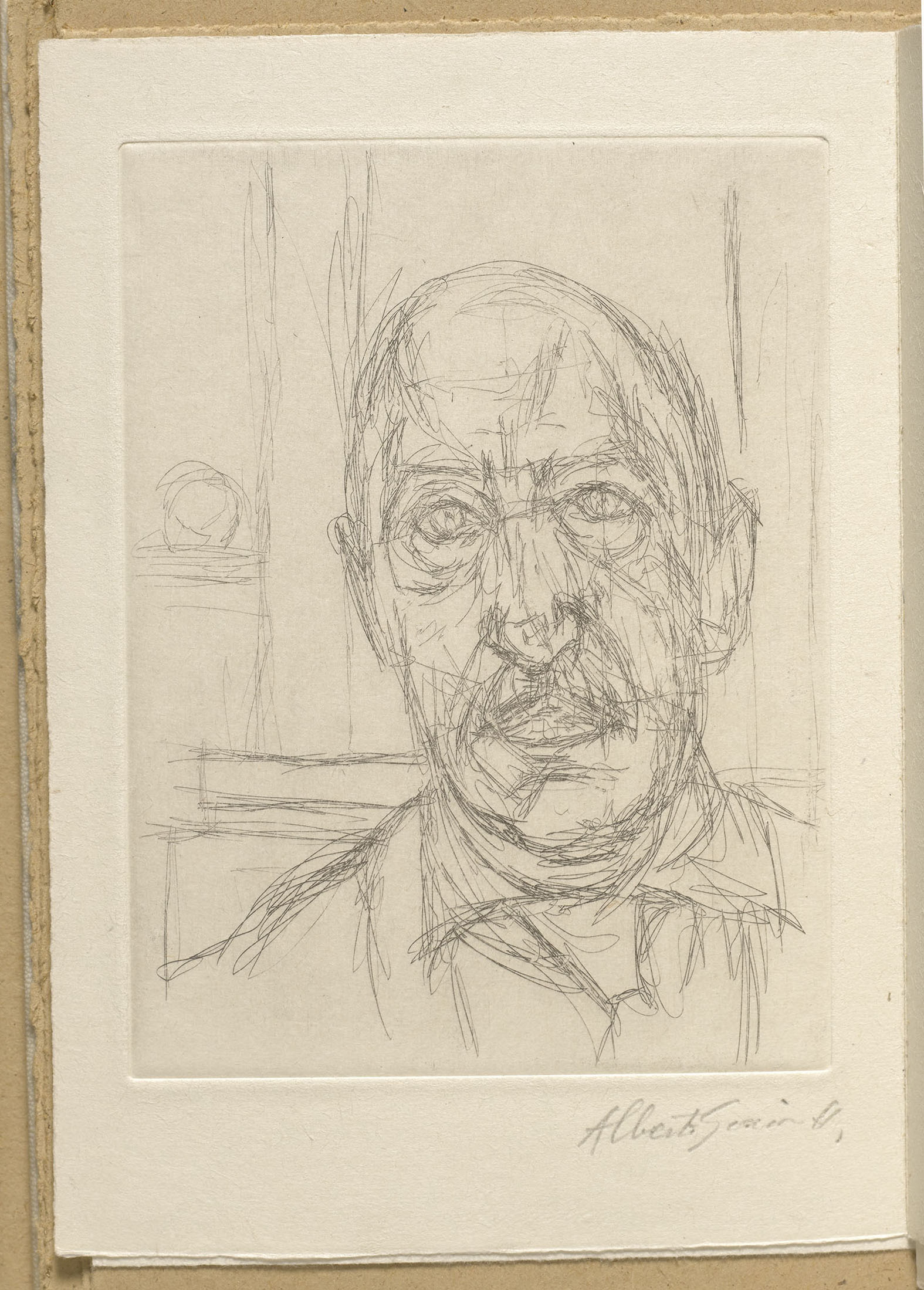

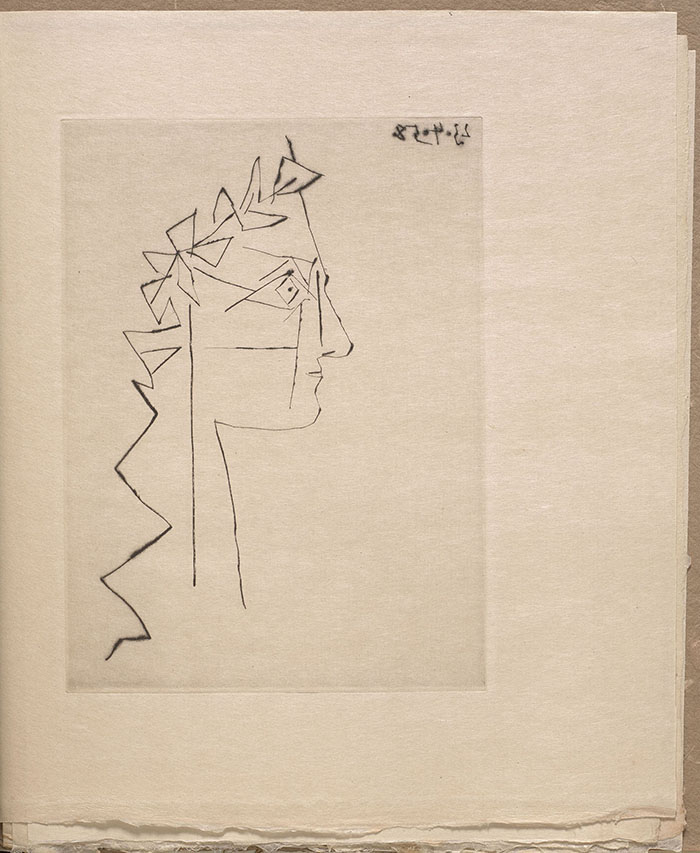

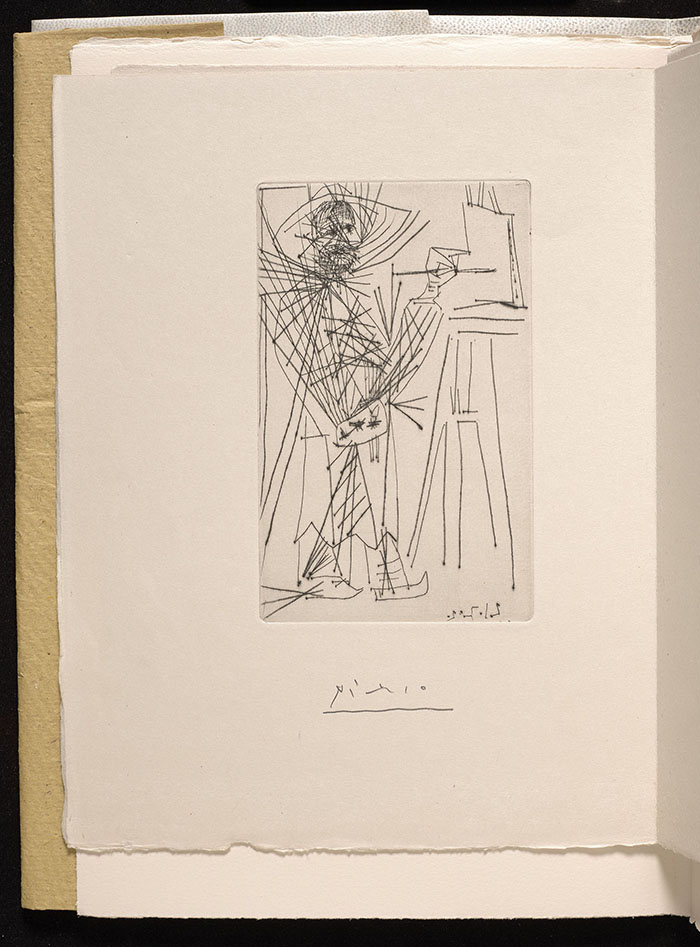

It was with Picasso’s support and encouragement that Iliazd launched his second publishing career, seventeen years after he had published LidantYU, his first book in Paris. The new book, published in 1940, was Afat, a prodigious sequence of more than seventy classical sonnets by Iliazd in Russian, with etchings by Picasso. Afat marked the beginning of their long artistic partnership.

Picasso ultimately was the sole illustrator for seven of Iliazd’s books and a contributor to two others. Though Picasso has many illustrated books to his credit, it’s been said that Iliazd was the only publisher from whom he would take direction. The two completed their last project together in 1972, four months before Picasso’s death.

I do not publish editions for monetary gain. I struggle. I have always struggled for an idea, and if I published such and such an author, it is always to bring attention to an unknown, and not only to reestablish him, but also to turn the tide of ideas toward him, to revise, once again, human values.—Iliazd, letter to Joan Miró, May 4, 1962

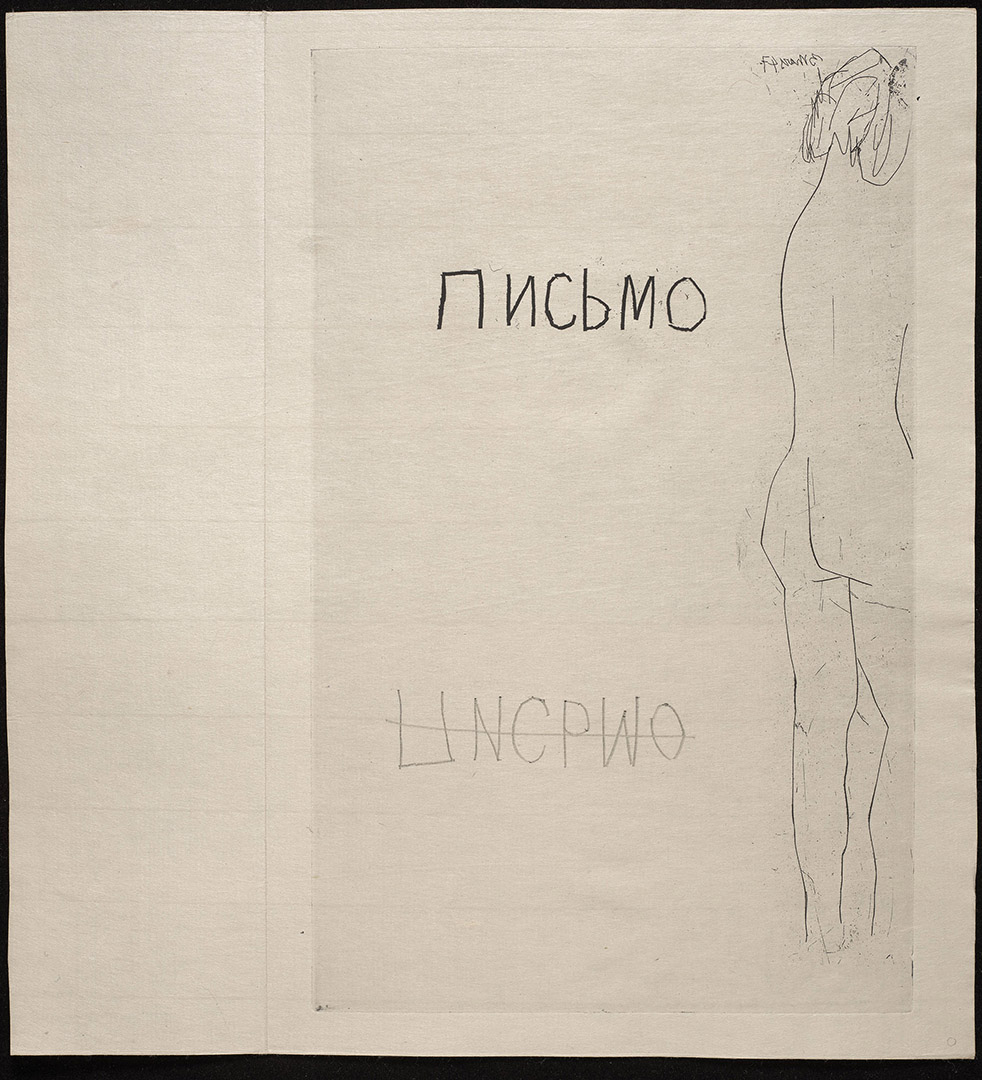

In 1946, in Cannes, Iliazd met Olga Djordjadze, a young compatriot with whom he could speak Russian—something which gave him great joy. . . . Thus “Pismo” was born— a love ‘letter’ to a transitory companion with whom Iliazd traveled through Provence.—Patrick Cramer, Pablo Picasso, the Illustrated Books: Catalogue Raisonné

Iliazd’s Other Books

Books we have profiled in this section include only those we have ready access to, the sixteen currently held in the Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books. The five others that Iliazd published in Paris:

- Traité du balet, Jehan-François de Boissière/Marie-Laure de Noailles (1953)

- Récit du nord, René Bordier/Camille Bryen (1956)

- Ajournement, André du Bouchet/Jacques Villon (1960)

- Poèmes et bois, Raoul Hausmann (1961)

- Boustrophédon au miroir, Iliazd/Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes (1971)

For detailed discussions of these, as well as the books we have summarized in the main body of this chapter, see Johanna Drucker’s Iliazd: A Meta-Biography of a Modernist, Johns Hopkins University Press (2020).

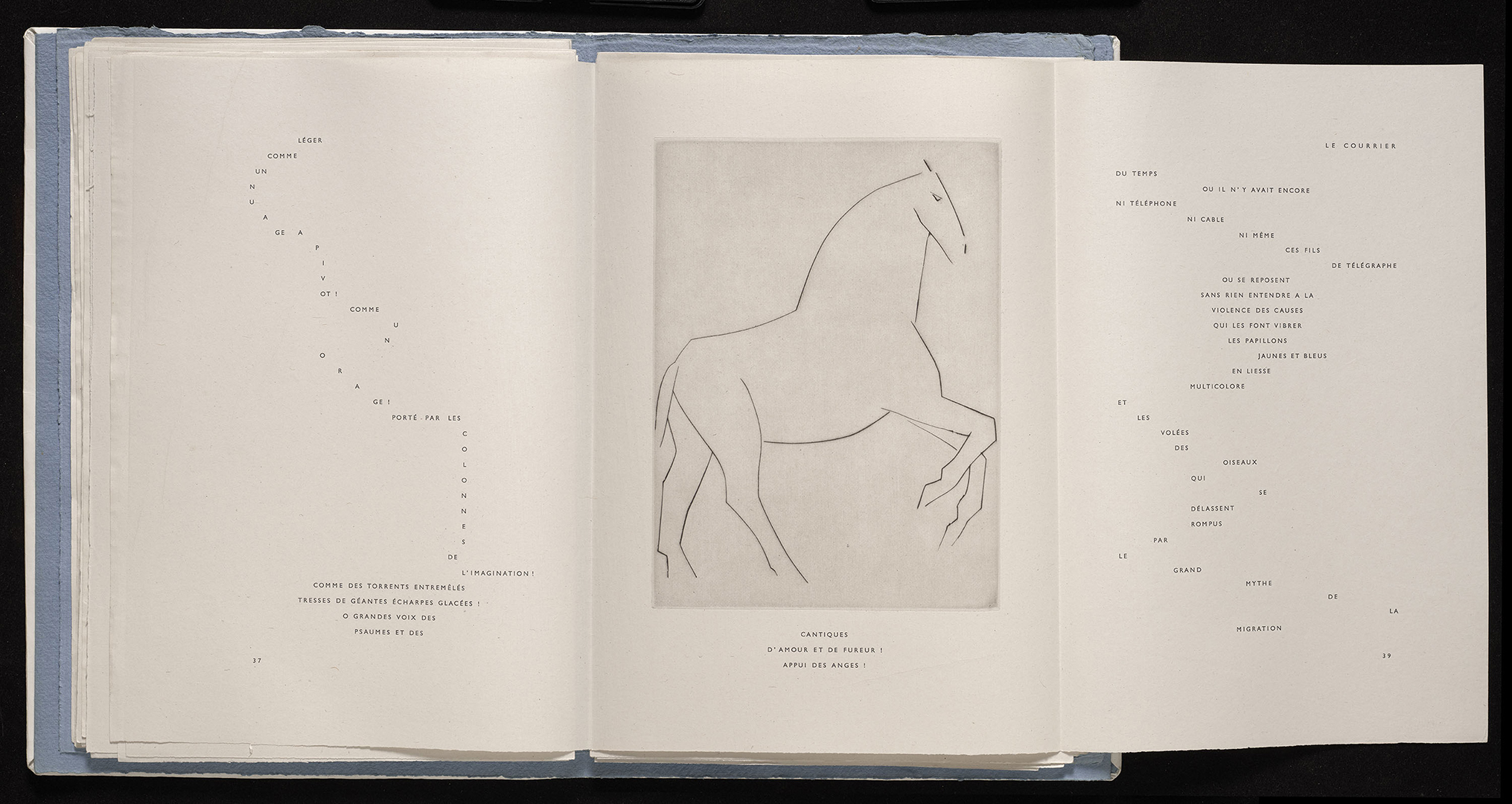

Evolution of the livre d’artiste

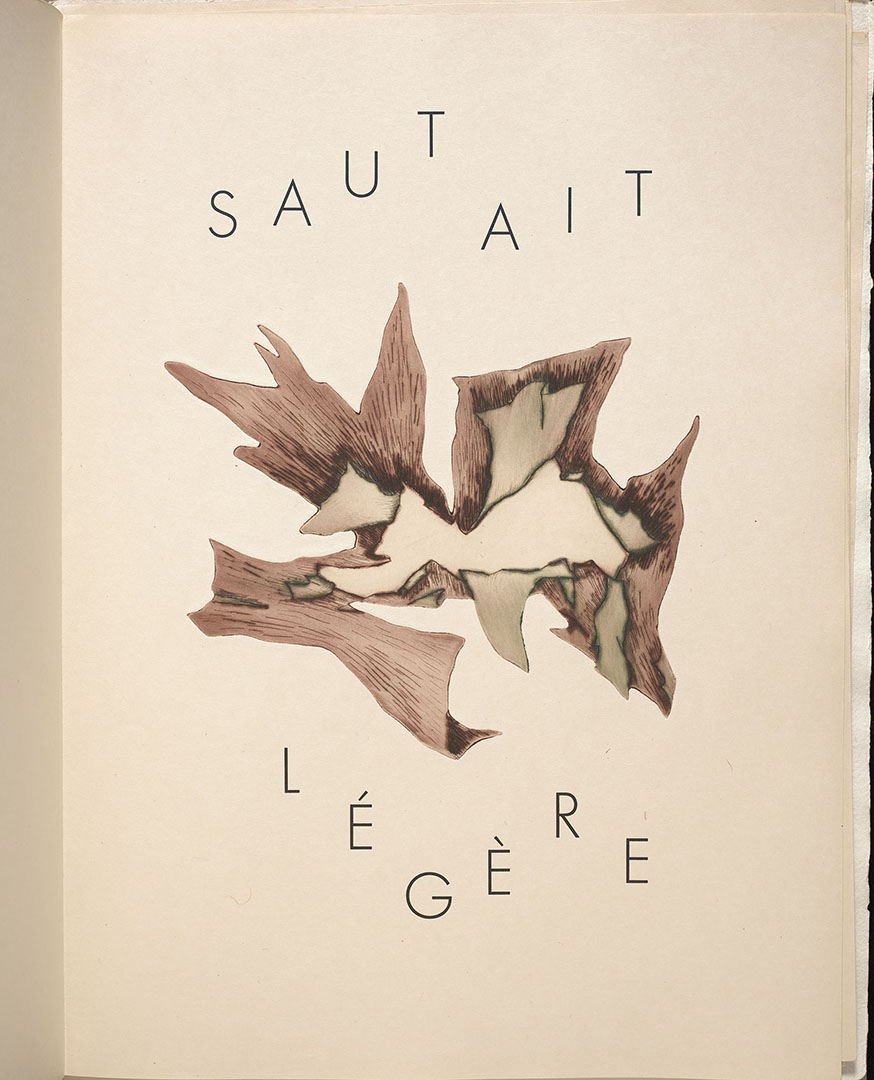

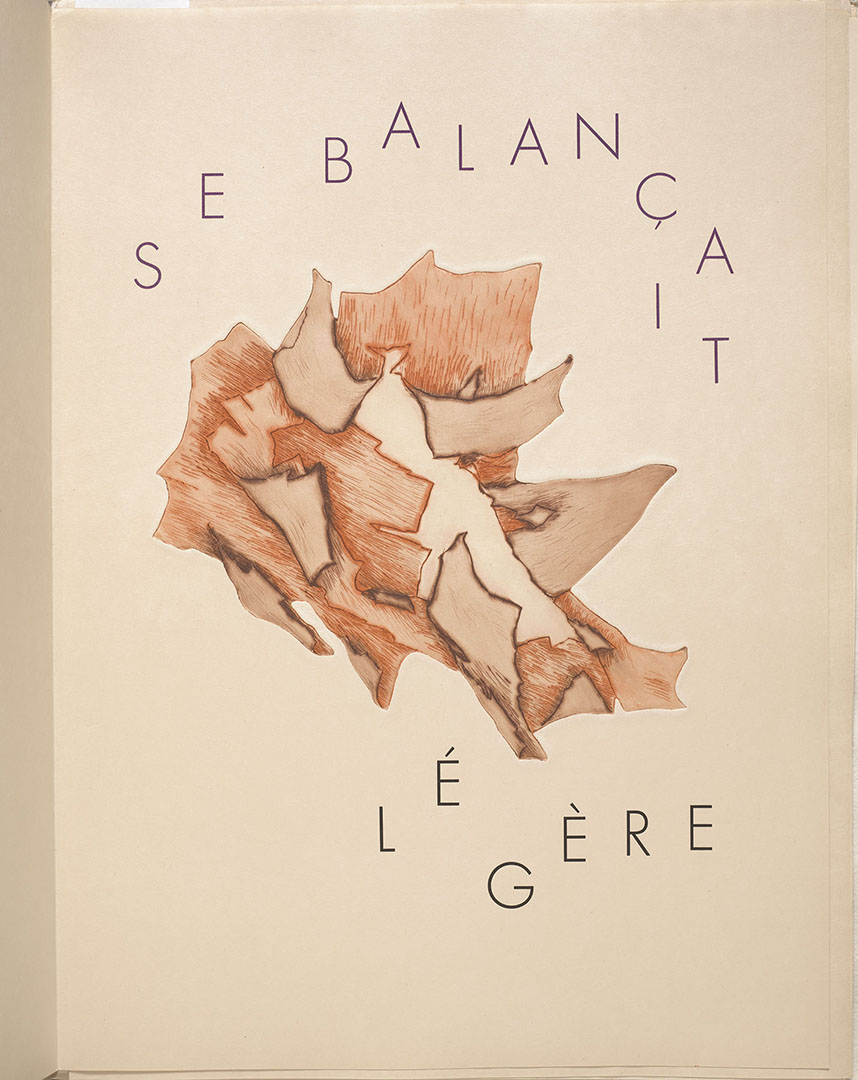

However valuable it may be on its own terms, the livre d’artiste is most often regarded not as an artwork in itself, but rather as a high-concept container for a suite of fine art prints. In deviating from this norm, Iliazd transcended the genre. By creating visual forms for literature and a deeply engaging experience for the reader, he turned the book into a multidimensional, interactive work of art. If his books are a far cry from the relatively static editions of most livres d’artistes, they are fully in keeping with the mission of an artist of the avant-garde. His ability to sustain this practice in the high-craft realm of the livre d’artiste while working with the most prominent artists of his time lends his work an unparalleled distinction.

How did he do it? Looking at his books today, we can see the deep thinking and ingenuity that were the foundations of his practice. We can also see why artists wanted to work with him: with Iliazd, they were not merely illustrators but collaborators in the creation of complex, hybrid works of art. That distinction means everything: the realization of the book itself as a work of art is Iliazd’s enduring legacy.

The Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books

Over a period of twenty years, the Chicago collectors Reva and David Logan built one of the great private collections of artists’ books and in 1998 donated that collection to the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, home of works on paper at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

With more than four hundred carefully assembled titles, the Logan Collection contains many of the most important works in the genre, with significant artists’ books representing virtually every major art movement dating from the beginnings of the livre d’artiste in the late nineteenth century. Augmented by important works already held by the Achenbach Foundation, the Logan gift established the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco as stewards of one of the most historically significant collections of artists’ books in the United States.

The Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books holds sixteen of the twenty-one books Iliazd published in Paris from 1923 to 1974.

This Project

As the only works of art that must be handled to be fully experienced, artists’ books present a challenge for an institution charged with their conservation and display. The current project addresses this challenge by making contents of, and related information about, selected books from the collection available online using the affordances of digital media. The project aims to raise the accessibility of the collection and create greater public understanding and awareness of what critic and historian Johanna Drucker has called “the quintessential twentieth-century art form.”

Major support for this project has come from three Logan family foundations: The Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Revada Foundation, and The Reva and David Logan Foundation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Iliazd: Publishing as an Artform website is by far the most extensive of the three sites we have produced devoted to work in the Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books. It draws on a broad and deep range of scholarship and other resources that have been made available to us. Foremost among these resources is the Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books itself, a gift of inestimable value presented by the Logans to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in 1998.

Since 2016, we have received significant ongoing financial support from Logan family foundations. We would particularly like to thank Jonathan Logan and the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation for making possible the current website, a related symposium, and much more. Jonathan has championed this project since its inception in 2015. Special thanks also to Daniel Logan and the Revada Foundation for supporting our work in 2021, extending our ability to further document and research the collection and present our findings to a broader public. We thank the Achenbach Graphic Arts Council for a supplemental grant this year that helped support work on the Logan Collection database by AGAC Logan Fellow Araceli Bremauntz-Enriquez, whose work has been exemplary.

For the Iliazd project:

We give wholehearted thanks to François Mairé, Iliazd's stepson and custodian of the artist's legacy. Mairé, who leads the Iliazd Club in France, has graciously authorized us to reproduce much of the archival material we have presented here and has offered suggestions and corrections for the website.

Boris Fridman, a prominent collector and curator of Iliazd's oeuvre, has made several visits to San Francisco, providing us with catalogs of exhibitions and sharing his knowledge and high opinion of the artist's importance in the history of twentieth-century art.

Johanna Drucker's writing on Iliazd has been invaluable. Her long-awaited book Iliazd: A Meta-Biography of a Modernist, by far the most complete and authoritative account in English of Iliazd's life and work, was published in late 2020 by Johns Hopkins University Press. It is a must-read for anyone interested in this artist. Before her book's publication, Johanna graciously agreed to read over an earlier version of our website's text and made several suggestions and corrections. Her work on Iliazd extends back at least to 1988, with an article in The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. She later gave prominent mention to the artist in her 1996 book, The Century of Artists' Books; many of its readers encountered Iliazd there for the first time.

In the 1987 catalog of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Françoise Le Gris wrote a detailed and illuminating essay that included many extracts from Iliazd's archive and other sources, previously unavailable in English. We have drawn heavily on the essay here. Over the years, she has continued to be a leader in Iliazd scholarship.

Thomas Kitson's introduction to his translation of Iliazd's novel, Rapture, published in 2017 by Columbia University Press, has also been invaluable. It contains essential information about the artist's artistic development, drawing to some extent on scholarship published in Russia. Funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation has allowed us to commission Kitson's English translations from Russian in Iliazd's artists' books, which we are making freely available.

David Sume's 2019 doctoral dissertation at the University of Montréal, The Architectural Nature of the Illustrated Books of Iliazd, is an impressively deep analysis of the structural properties of Iliazd's books, providing us with many insights.

We are grateful to Andrei Ustinov, an important scholar of Russian Futurism, who read this website's manuscript and made several additions and corrections.

In France, Régis Gayraud, a prominent writer and scholar of Iliazd and his time, is an authoritative source. Also in France, the acclaimed writer André Markowicz has translated much of Iliazd's Russian text into French and has written movingly of working as a young scholar on Iliazd's archive with Iliazd's widow, Hélène.

Finally, colleagues at the Fine Arts Museums who have supported this work include Karin Breuer, Curator in Charge at the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts; in Web and Digital Production, Diana Murphy, Meenal Tyagi, Simone Polgar, director Patricia Buffa, and Andrew Fox; in Photo Services, director Sue Grinols and photographers Randy Dodson and Jorge Bachman; and Digital Asset and Rights Manager Robert Carswell. Our Department of Publications has provided essential support, thanks to the work of editors Trina Enriquez and Victoria Gannon, with oversight from Director of Publications Leslie Dutcher and Associate Director of Education Emily Jennings. Many thanks to all.

Stephen Woodall

Collections Specialist, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

May 2021