de Young museum

November 17, 2018–June 23, 2019

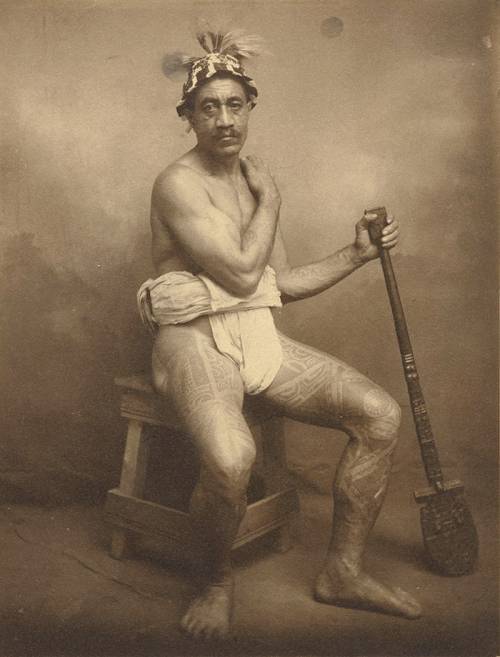

Māori and other Pacific works on view in expositions and museum exhibitions in the late 19th century introduced tens of millions of people from around the globe to diverse artistic styles of the region.

Gauguin’s exposure to Māori art might have begun at the 1878 Universelle Exposition in Paris. He also frequently visited the anthropological collection rooms of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris, which opened in 1882.

Displays of artworks from the Pacific in Gauguin’s time often included objects similar to this gable figure, or tekoteko. Māori stories tell of Tangaroa, the god of the sea, who captured Te Manuhauturuki. Tangaroa placed Te Manuhauturuki’s immobilized body on the gable of his house under the sea, creating the first tekoteko. The carved ancestor of this tekoteko is depicted in a war dance posture (haka) with his full-face tattoo (rangi paruhi) and abalone shell (paua) eyes.

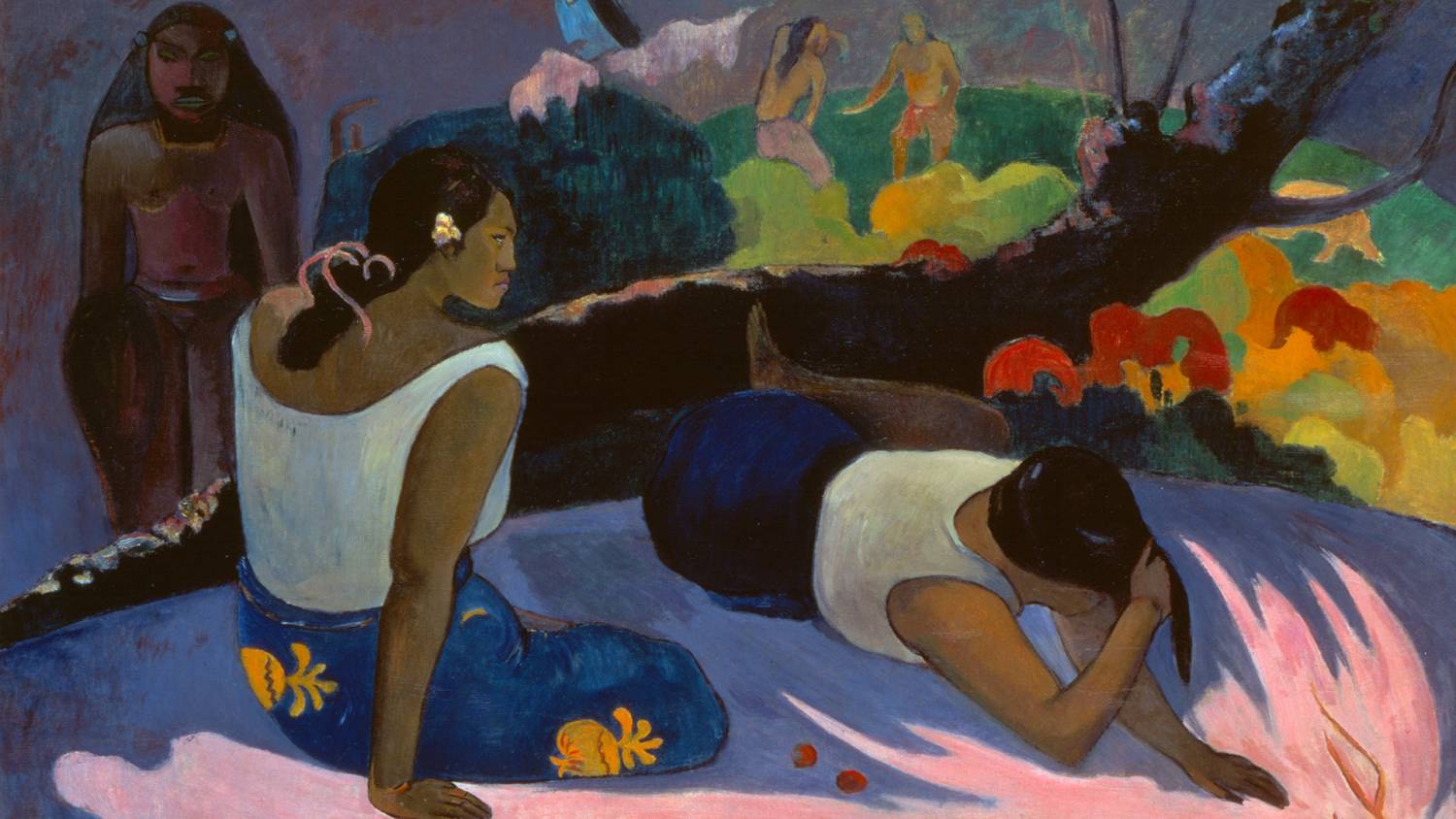

In April 1891 Gauguin traveled to Tahiti under the auspices of the French Ministry of Fine Arts, “in order to execute a number of paintings from a country whose character and light I [Gauguin] wish to capture.” That fall, Gauguin painted twenty scenes of village life. This composition corresponds to colonial, ethnographic-style photography of the time, showing figures engaged in their daily routines and represented within an idealized Tahitian landscape, as a European audience would perceive it. In their placement, the seated, standing, and walking figures play a decorative role as forms that lead the eye to into the depths of the landscape.

Gauguin remarked, “In the Marquesan especially there is an unparalleled sense of decoration . . . the basis is the human body or the face, especially the face. One is astonished to find a face where one thought there was nothing but a strange geometric figure.”

The connected figures on the lid of this box represent Papatūānuku, the earth mother, and Ranginui, the sky father, the primordial parents of the Māori.

According to the Māori origin story, the many children of Papatūānuku and Ranginui were gods who lived in the dark space between their parents’ embrace. The children eventually succeeded in separating their parents and creating the world.

The entire surface of this box has been carved with designs composed of notches and parallel grooves, known as rauponga.

Abalone shell (paua) insets have been used to represent the eyes.

Gauguin’s legacy is intrinsically linked to the global art market being a beneficiary of colonialism in the Moana [Pacific].Yuki Kihara, An excerpt from the exhibition catalogue, 2018

de Young museum

November 17, 2018–June 23, 2019

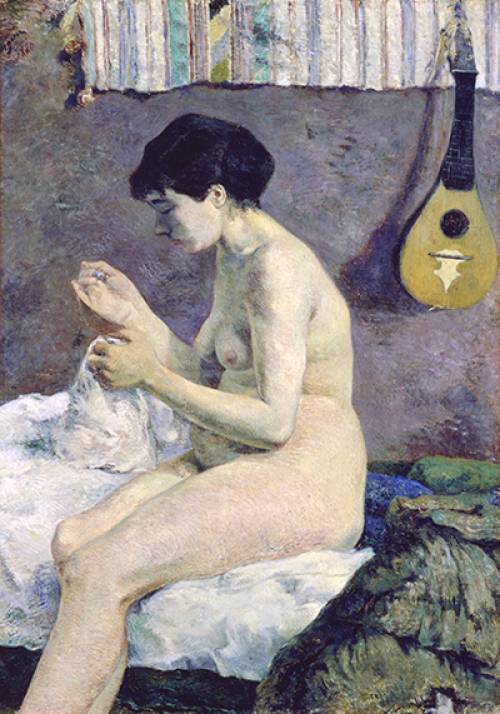

The sitter is shown not as an idealized nude but with a slouched posture and actively focused on her sewing.

The artist’s broad brushwork and use of flat zones of color hint at the future direction of his work and his divergence from Impressionism.

The large green mass, possibly representing bedding, foreshadows Gauguin’s mature style, in which he regularly included enigmatic details for decorative effect.

This life-size study was featured in the sixth Impressionist exhibition in 1881 and was praised by the critic Joris-Karl Huysmans for “representing a woman of our time.” Gauguin’s son Pola identified the subject as a family nursemaid, Justine, but the identity of the sitter remains a matter of speculation among scholars.

After traveling the globe with the merchant marines and navy, Gauguin returns to France in 1871. In 1883, he starts working exclusively as an artist. The family moves to Copenhagen in 1884 to live with Mette’s family. Gauguin struggles personally and financially during his time in Denmark. He returns to Paris in 1885 and voyages to Martinique in 1887.

Returning from the Caribbean, Gauguin settles in Paris with his good friend Émile Schuffenecker and then travels again to Brittany (which he had first visited in 1886). In October, Gauguin goes to Arles to work with Vincent van Gogh. Gauguin’s visit lasts just a few months before ending tragically with Van Gogh’s self-mutilation and Gauguin’s abrupt departure back to Paris.

In Paris in the spring of 1889 Gauguin develops an independent group exhibition displayed concurrently with the Exposition Universelle. He then returns to Brittany, where he remains plagued by financial concerns.

After a successful auction of his work and a final visit with his family in Copenhagen, Gauguin departs for Tahiti in 1891. Arriving on the island, Gauguin settles in a coastal community. Although he struggles with health issues and financial hardship, his letters state that he is “fairly pleased” with his work.

Destitute, Gauguin is repatriated to France, arriving in Marseille with 66 new paintings. He lives in Paris and travels in 1894 to Brittany, where he is seriously injured during a street fight, which keeps him bedridden for months. Disillusioned by life in France, Gauguin plans to return again to the tropics.

Gauguin returns to Tahiti, where he paints, builds himself a home, and writes an essay on theology that includes a critique of marriage and the Catholic church. In 1901, in pursuit of a less colonialized environment and to avoid the rising cost of living, Gauguin settles in the Marquesas Islands, where he lives until his death on May 8, 1903.

After meeting Gauguin at Arosa’s home, Pissarro became his friend, mentor, and teacher. Gauguin later described Pissarro as “one of his masters.” The two artists often painted the same scene when working together at Pissarro’s home in Osny, a village northwest of Paris. Pissarro also encouraged Gauguin during his early career, inviting him to participate in the fourth Impressionist exhibition in 1879.

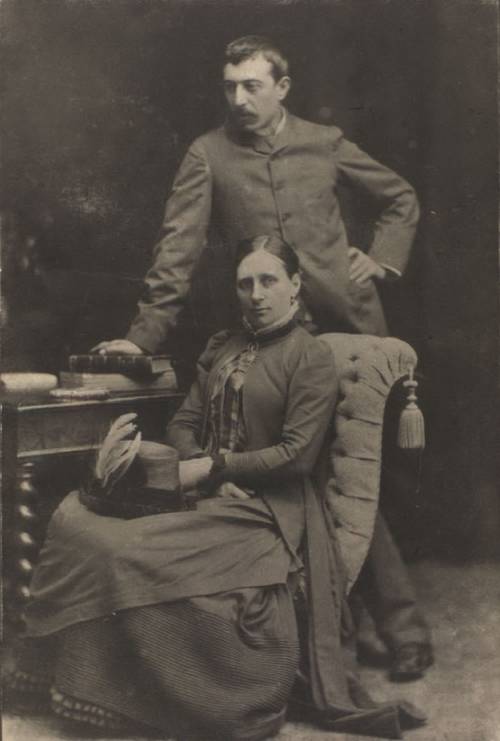

Though marked with extreme difficulty, Gauguin’s marriage to Mette Sophie Gad was the artist’s most enduring relationship.

Gauguin’s decision to become an artist and his compulsion to travel abroad led to his estrangement from his wife and family. According to Emil, the eldest of five children, “She [Mette] agreed to let him go, not because she had faith in his genius, but because she respected his passion for art. It was brave of her. It meant she was to assume the burden of maintaining [raising] and educating the children.” Separated for eighteen years, they never divorced and regularly corresponded until 1897. Mette promoted Gauguin by organizing several exhibitions and by selling his work. Numerous works in the exhibition belonged to Mette or passed through her hands.

When Mette and Gauguin married in 1873, he was working in Paris as a stock broker and was able to provide a comfortable middle-class lifestyle for their family, which grew to include four sons and a daughter. Gauguin’s exposure to the extensive art collection of his guardian, Gustave Arosa—including works by Eugène Delacroix and the foremost artists of the French Salon as well as ceramics from around the world—contributed to his developing passion for art. He further cultivated his interest by collecting more than fifty works by artists including Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, and Edgar Degas.

Painted circa 1881, the subject, composition, and painterly qualities of this large canvas show the influence of fellow artists such as Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Representing a moment of peaceful domesticity characteristic of many Impressionist paintings, this work pictures a woman, perhaps Gauguin’s wife, Mette, or a nurse, and three of his children in the garden near their first house in Paris.

In a letter to Pissarro, Gauguin described their home at 8 rue Carcel, in the 15th arrondissement of Paris, as three rooms and a studio.

I quite understand that this lousy painting has been your ruin but since the harm is done you should accept the position and try to derive profit therefrom for the future.Paul Gauguin, letter to Mette, May 1886

Gauguin’s relationships with and representations of women are a central theme in the artist’s career. This aspect of Gauguin’s biography can be challenging for some contemporary viewers given current views about sexual morality and women’s rights.

While living in Tahiti and the Marquesas, Gauguin had relationships with at least three women: Teha’amana (Tahiti), Pau’ura a Tai (Pahura) (Tahiti), and Vaeoho Marie-Rose (Marquesas Islands), who each bore one or more of Gauguin’s children. These companions ranged in ages from 13 to 15, within the legal age of consent (13 in France at that time; 10 in California), and at least two of the relationships were perhaps facilitated by adult relatives. However, the women’s own preferences in entering these relationships are not documented or otherwise known. They were mentioned in his letters, featured in his journals, and were the subjects of many of his most striking artworks. They appear as models, muses, mothers, companions, and lovers—and as a Tahitian Eve. While Gauguin is the source for most of what we know about the lives of these young women, new research is revealing more about their personal stories.

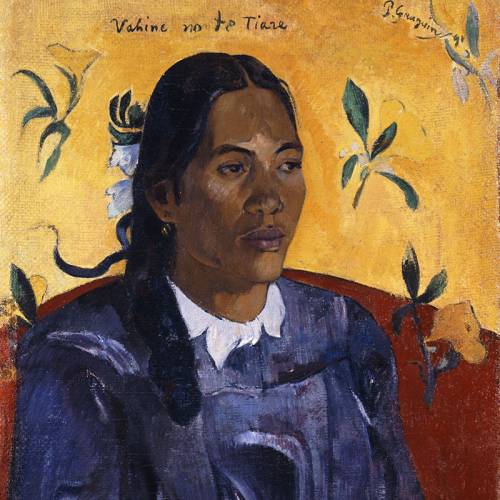

Tahitian Woman with a Flower was among the first paintings Gauguin produced after his arrival in Tahiti in 1891. The sitter is a neighbor who agreed to model for the painting, only after donning a colonial dress of the period. The background of floating flowers infuses the work with a sense of tropical beauty. However, the portrait is stylistically European and draws on Renaissance portraiture traditions, from the format to the pose of the sitter: a three-quarter figure, shown slightly in profile, with face, hair, and hands in place.

In this photograph, which was found among the artist’s effects after his death, Gauguin’s young model Tohotaua appears seated in the his Marquesan studio. In the background are European reference images, tools, and canvases. Within this setting, Gauguin posed Tohotaua dressed in the garment known as a pāreu and holding a fan. As the light from a nearby window falls across her arms and lap, Tohotaua stares boldly at the viewer.

Mette Sophie Gad, who occasionally worked as a French tutor to support her family, was remembered as a social and warm-hearted member of her community in Copenhagen. The 20 years of correspondences between Mette and her husband reveal a relationship consumed with financial struggles, health issues, concerns about the children and their future, the emotional challenges of their estrangement, and his relentless pursuit of professional success.

Gauguin lived his life with the singular determination to follow his own spiritual journey and become an accomplished artist. Two compositions—one painted at the beginning and one near the end of his career, Still Life with Flowers and Flowers and Cats—document the artist’s ingenuity and also his challenges. In Still Life with Flowers, Gauguin unsettled his traditional subject with the abstracted bedpost at the right of the composition, foreshadowing the enigmatic Symbolist style of his future work. Gauguin often introduced elements in his pictures to make his viewers wonder and question. By comparison, Flowers and Cats includes a bouquet of flowers Gauguin cultivated from seeds sent from France by a fellow artist. Painted in Tahiti, at the encouragement of his dealer, the painting shows Gauguin’s inability to completely abandon the art market and the culture of Europe.

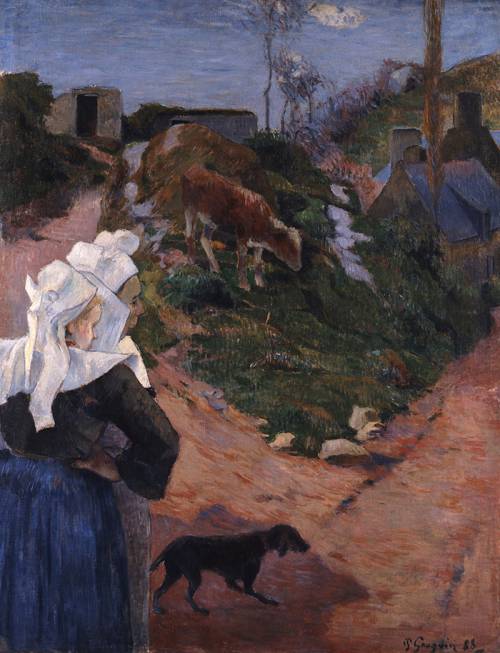

Of his time in Brittany Gauguin, wrote, “I like Brittany. Here I find the wild, the primitive. When my clogs echo on this granite earth, I hear the dull, muffled, powerful note that I am seeking in painting.” Gauguin’s Landscape from Brittany with Breton Women shows Brittany as an isolated French province, where time seems to stand still. The women wear their local dress complete with elaborate headdresses, and a cow ambles freely through a village. In Brittany, peasant beliefs blended Catholicism with ancestral practices, providing Gauguin with a world of symbols to inspire his art and spirituality.

After his arrival in Tahiti, Gauguin was eager to learn about Tahitian beliefs from local residents and sites. In his partially fictional memoir, Noa Noa, which he later published in Paris to promote his Tahitian paintings, Gauguin describes receiving instruction about Tahitian theology from his vahine—companion and model—called Tehura (Teha’amana). However, it is evident that he drew heavily on an account of the islands by Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout, Voyages aux îles du Grand océan, (Travels to the Islands of the Pacific Ocean), published in 1837. He used the text to infuse his paintings with religious images and themes. Although it looks like a painting from Tahiti, Gauguin painted Reclining Tahitian Women in Brittany in 1894 after his first sojourn to the islands.

Spirituality became a consistent theme within Gauguin’s work after his first stay in Brittany in 1888.

Gauguin sought to communicate universal truths in his art but also endeavored to create pieces that were enigmatic and open to interpretation, believing that he represented the complexities of the human experience. He aimed to expand his viewers’ consciousness, prompt questions, and inspire dreams.

A hint—don’t paint too much direct from nature. Art is an abstraction; draw it out from nature while dreaming upon it and concentrate more on the creative process than on the result, that is the only way to come close to God, namely doing the same as our divine master, creating.Gauguin, letter to Émile Schuffenecker, August 1888

Gauguin infused the scene with enigmatic symbolic imagery: a disembodied blue mask hovers above the two women.

The use of intense color, sweeping lines, and patterning is indicative of Gauguin’s later style.

Commenting in 1893 on Gauguin’s Tahitian work, Camille Pissarro stated, “Gauguin certainly does not lack talent, but . . . he is always poaching in the lands of others; today he is stealing from the savages in Oceania.”