Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books

Legion of Honor museum

The Book as Art

Alchemy on the Page

Introduction

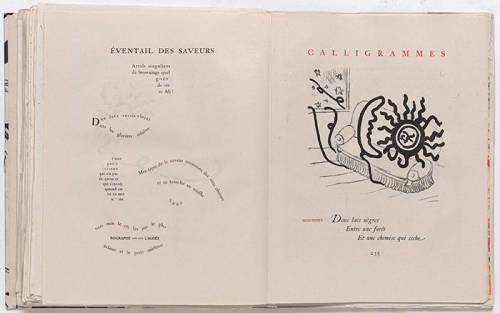

At the dawn of the twentieth century, avant-garde artists and writers throughout Europe discovered a new medium, the artist’s book.

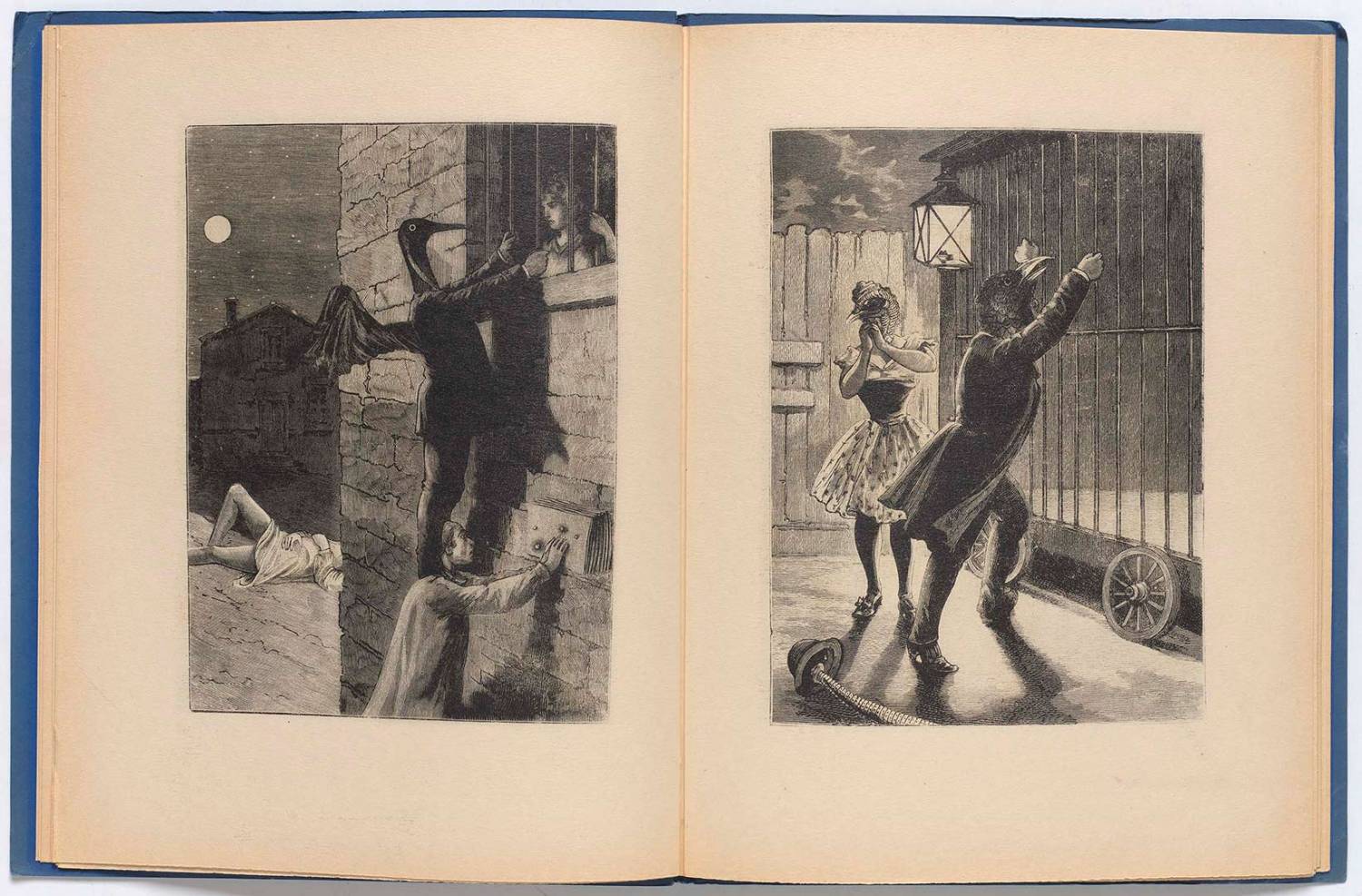

Although examples of books created as works of art can be found throughout history, from illuminated manuscripts to the books of William Blake, the art form as a widely practiced medium was born in the twentieth century, with approaches to artist’s-book publishing established early in the century. Luxury editions, called livres d’artistes, (literally “artists’ books,” but specifically denoting deluxe editions with original prints) were produced by established art dealers to promote the work of artists they represented, with the books often encased in deluxe bindings.

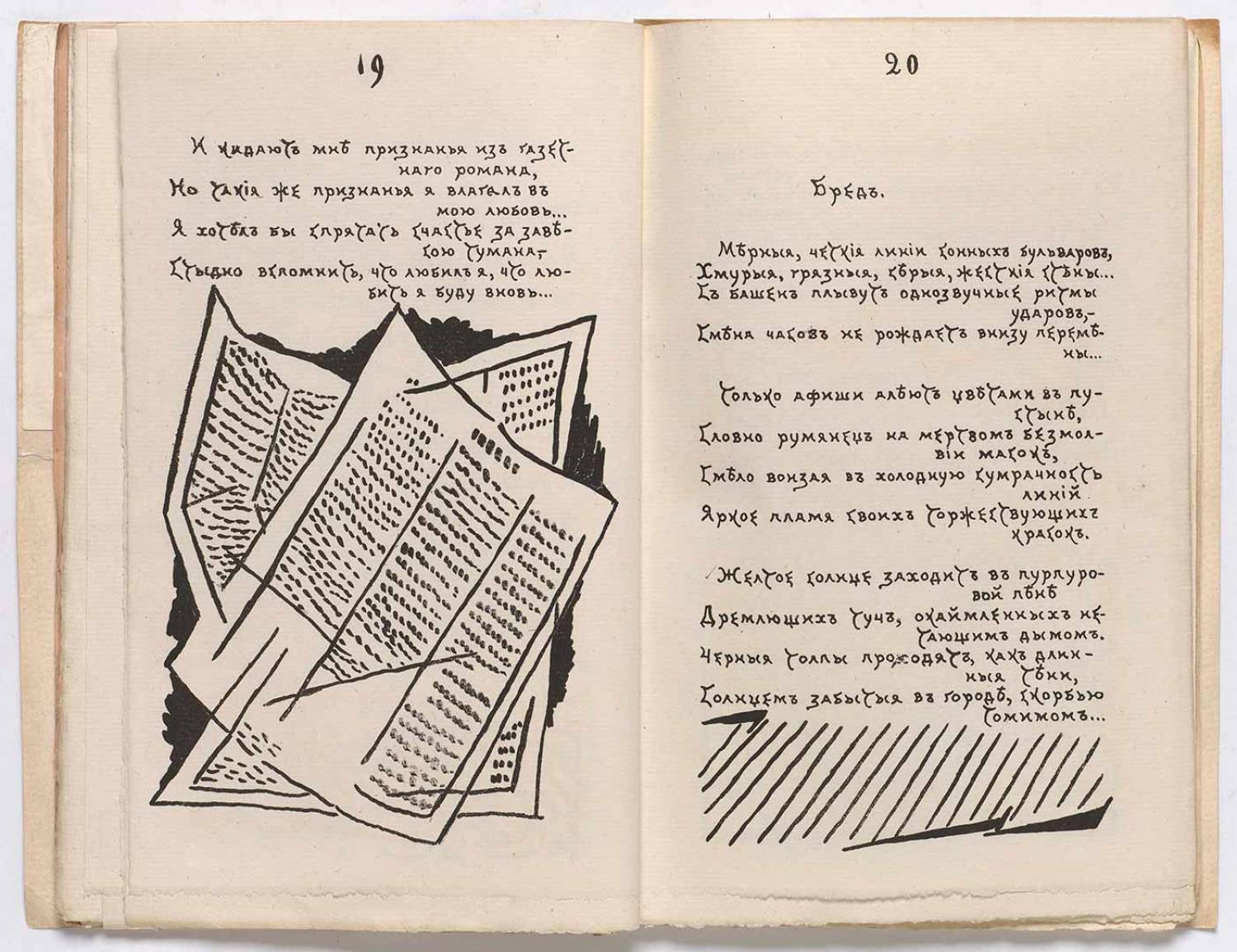

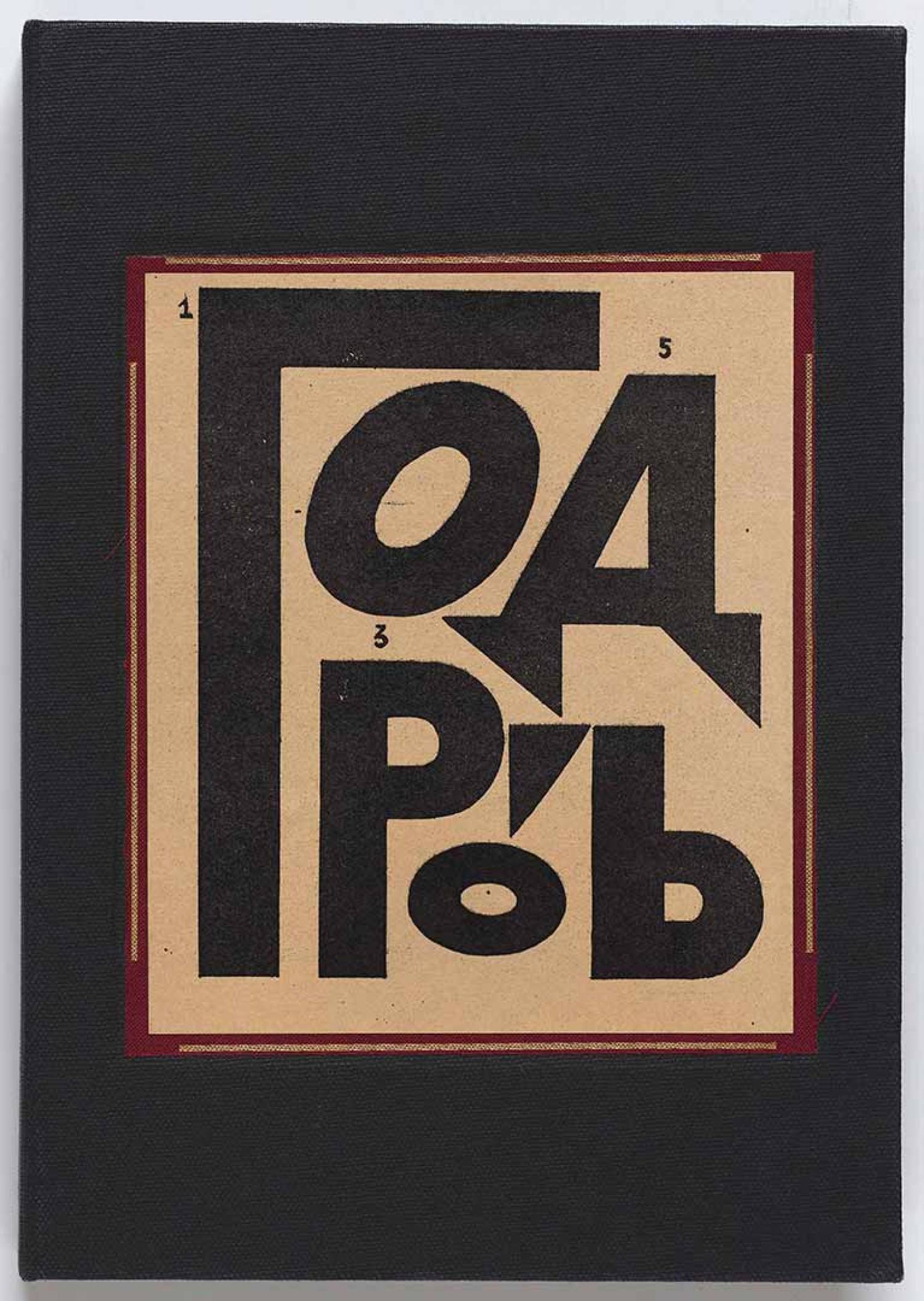

Meanwhile, avant-garde artists and writers, particularly in Russia, produced artistically adventurous works under their own auspices, less concerned with production values and focused more on the book as a hybrid art form. Paris was a major center for the production of livres d’artistes, while in Russia, daring experimentation with the form of the book itself set a standard for innovation. Today, more artists than ever are making books, following paths established more than 100 years ago.

The Development of an Art Form

1900

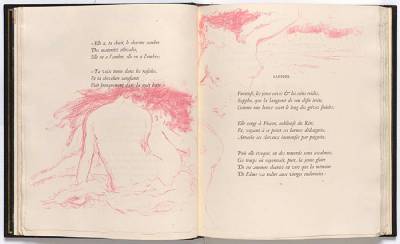

In 1900, art dealer Ambroise Vollard published what is considered the first modernist livre d’artiste, Parallèlement, with Pierre Bonnard’s original fine art lithographs illustrating erotic poems by Paul Verlaine. Commingling visual elements with poetry on the page spread was a radical design innovation at the time.

1909

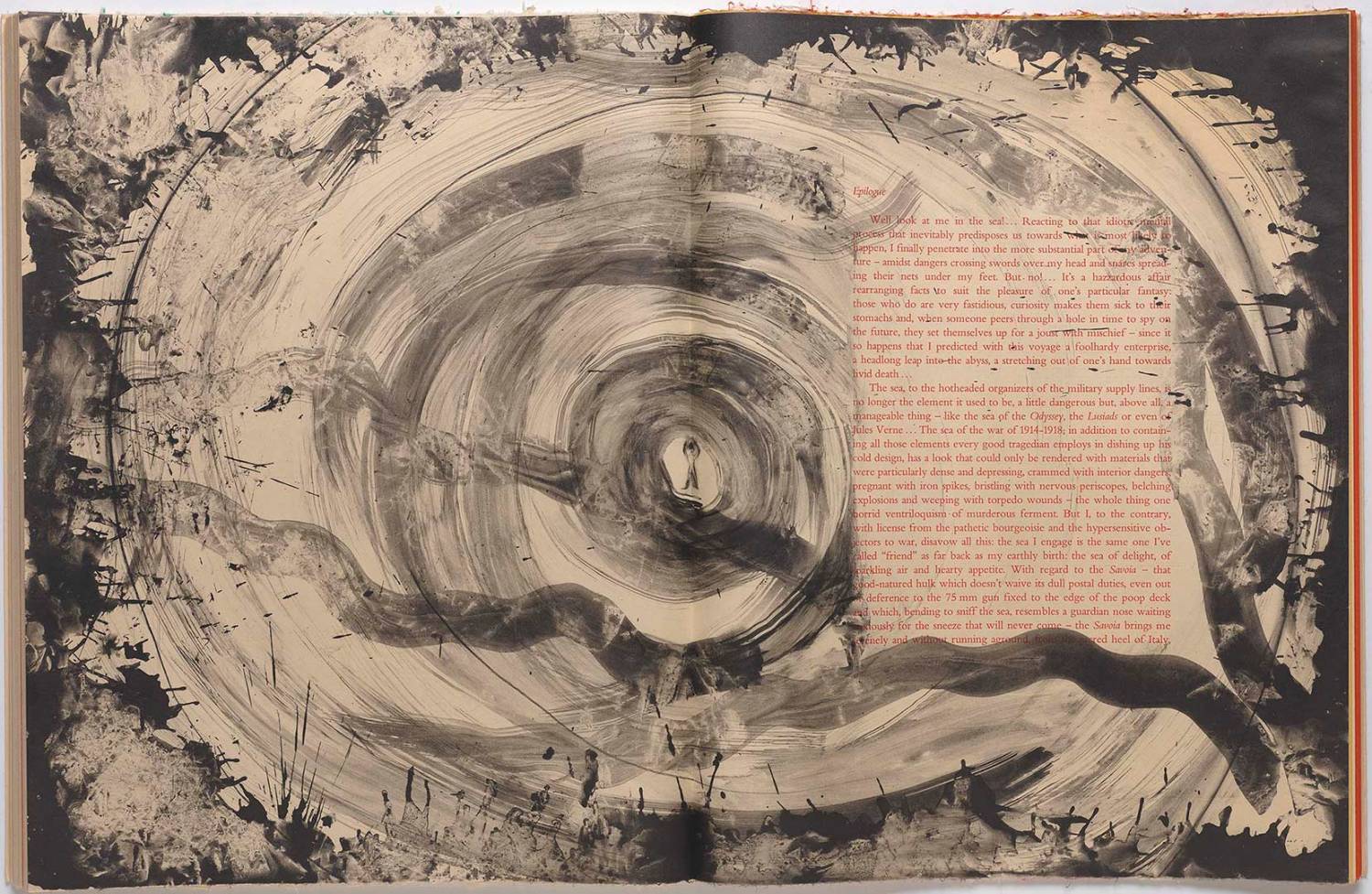

The principles of Futurism were set down in Italy by Filippo Marinetti in a series of manifestos that glorified movement, speed, and the Machine Age, paving the way for typographically adventurous publications. Russian Futurism, an independent movement, approached the book as a total work of art, an expressive synthesis of language and design, reenvisioning the form of the book itself.

1916

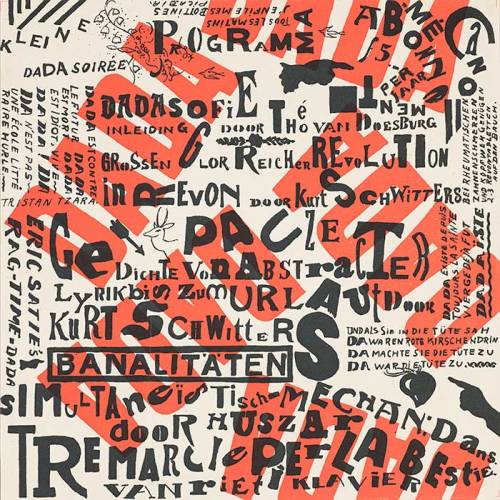

In response to the horrors of World War I, Dadaist poets and artists held a mirror of absurdity to the society they deemed responsible. They intended, as Jean Arp said, to “destroy the hoaxes of reason and to discover an unreasoned order.” Dada publications leaned heavily on collage and skewed type.

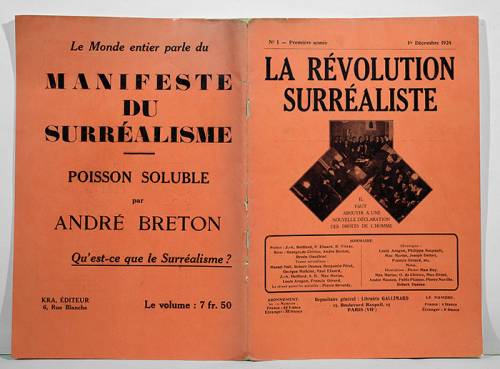

1924

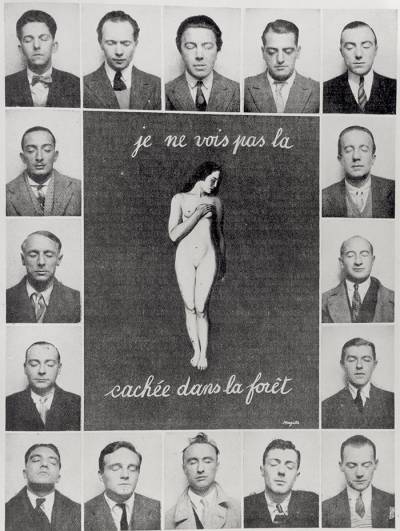

Unsatisfied with the nihilism of Dada, which he saw as a dead end, poet André Breton announced in 1924 the arrival of a new movement, Surrealism, invoking Freudian notions of the primacy of dreams and the unconscious. Surrealist writers and visual artists found the artist’s book to be a natural home for cross-disciplinary collaboration.

1960

In Europe, Dieter Roth reinvented the book as a conceptual work. A few years later, Ed Ruscha did much the same thing in America with Twentysix Gasoline Stations, the first in a series of books beginning in 1962. Both artists poked holes in the idea of the artist’s book as strictly a luxurious fine art commodity.

Communities of Artists and Writers

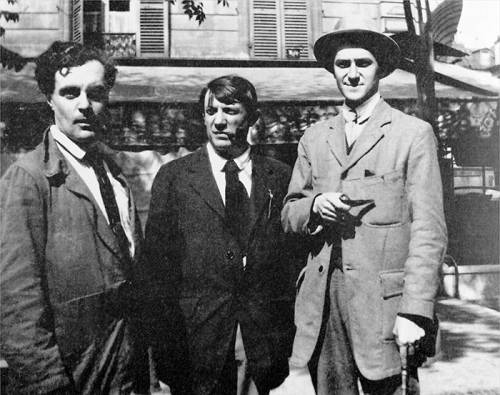

In Paris, the early twentieth century was a time when artists of all disciplines frequented the same cafes and salons. Artists and poets had a strong affinity—eager to collaborate, they found the book to be an opportune medium. The extent of these creative partnerships, particularly in France but common also in Russia, may have been unprecedented. Work preserved in the Logan Collection captures the spirit and momentum of successive cultural movements created by artists and writers.

The Art of Publishing

Two visionary Parisian art dealers provided an early impetus for what would soon become a widely practiced art form.

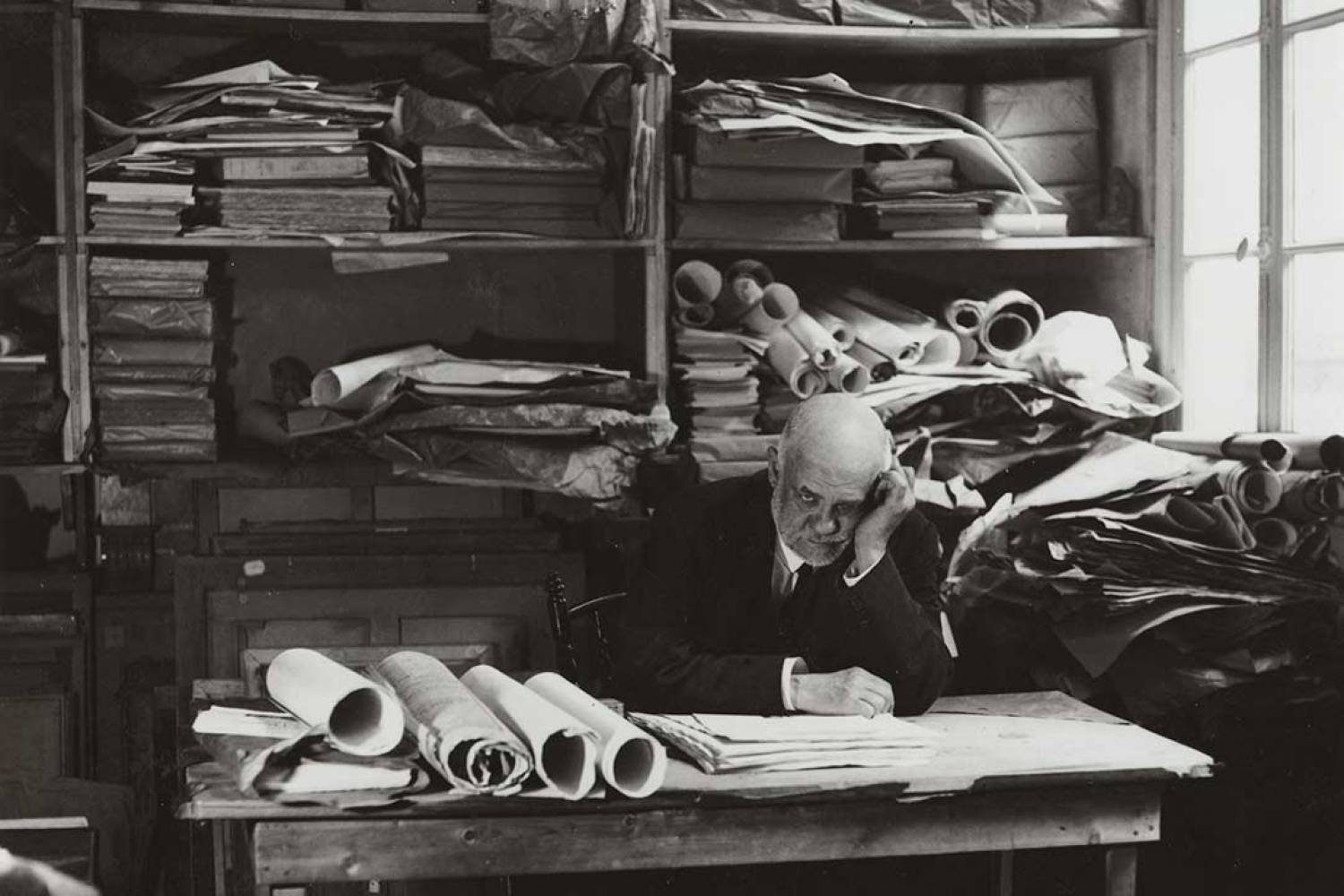

Born in 1866, Ambroise Vollard established his first gallery in 1893 and began publishing livres d’artistes in 1900 with the debut of Parallèlement (Bonnard/Verlaine). One of the most successful gallerists of his time, he took a particular interest in livres d’artistes, producing editions with many of the great artists of the era, including Auguste Rodin, Raoul Dufy, Odilon Redon, Pablo Picasso, Georges Rouault, and others. He published twenty-four titles in all, leaving twenty-seven more projects in progress at his death, in 1939.

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, born in 1884, was known for his prescient early support of the Cubist work of Picasso and Georges Braque, as well as his insightful appreciation of little-known writers of the avant-garde. The first livre d'artiste under his imprint, L’enchanteur pourissant (1909), was Guillaume Apollinaire’s first book, and featured André Derain’s first book illustrations. Subsequent artist/author pairings under Kahnweiler’s imprint included Max Jacob with Picasso and Apollinaire with Dufy, both in 1911.

To a greater extent than at any time since the Renaissance, painters, writers, and musicians lived and worked together and tried their hands at one another’s arts in an atmosphere of perpetual collaboration.Roger Shattuck, The Banquet Years, 1968

Artists’ books present a unique vantage point from which to gain insight into a succession of revolutionary movements, from Abstraction to Cubism to Futurism to Dadaism to Surrealism and beyond, and the positions of artists within those movements. Virtually every art movement from the beginning of the twentieth century up to now has produced its testaments in book art, a phenomenon that has escaped the notice of many art historians. The deeply hybrid nature of an artist’s book affords a wider context for understanding and appreciating the spirit of a particular time.

By revealing the artist’s relationship to a literary work or art movement, an artist’s book can provide a deeper understanding of the artist than we otherwise might have.

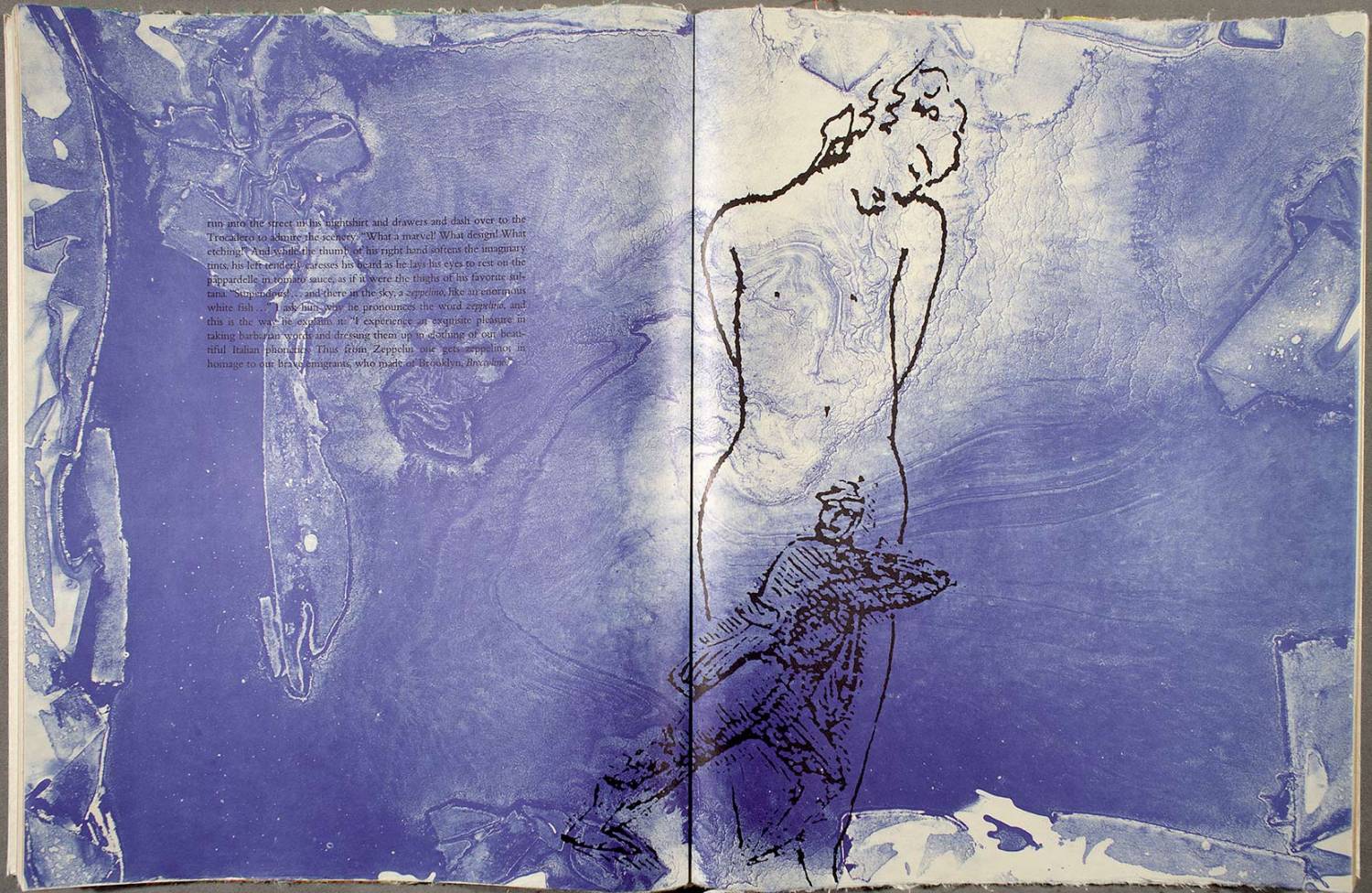

A Surrealist’s Tribute

Twelve years after the death of Apollinaire, who had coined the term “surrealism” and whose verse frequently made reference to the sun and stars, his friend Giorgio de Chirico paid him homage with an illustrated edition of one of Apollinaire’s most adventurous books. The artist’s vision connects the sources of heavenly light with the modern phenomenal world. It was a highly original interpretation of the work of a poet who had an immeasurable impact on the artists of his time, yet who did not live to see his vision of Surrealism take root as perhaps the most far-ranging, pervasive art movement of the century.

The Birth of Abstraction

With Klänge, Wassily Kandinsky was engaged in a quest to merge image and text in synergistic expression, here evoking sound (klänge) to effect a deeper resonance. The horse and rider image appearing throughout the book is Kandinsky’s symbol for the pathfinder, in this case finding a way beyond representation in art. The boldly experimental nature of this work, in both text and image, inspired the Dadaists and Futurists. Kandinsky was an “artist’s artist,” and Klänge, though commercially unsuccessful, was perhaps the most influential artist’s book of its time.

There was no art form that [Kandinsky] had tried without taking completely new paths, undeterred by derision and scorn. In him, word, color, and sound worked in rare harmony.Hugo Ball, Die Flucht aus der Zeit (Flight Out of Time), 1927

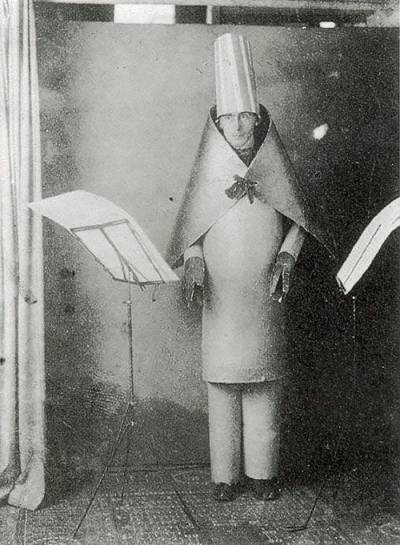

The Design of Absurdity

Founded in 1916 in Zürich, Switzerland, by poets and artists who gathered at Cabaret Voltaire, the Dada movement quickly spread throughout Europe and to New York, only to be ultimately eclipsed by the advent of Surrealism. This lithographed poster advertising a series of Dada soirées in the Netherlands, visually captures the anarchic spirit of Dada.

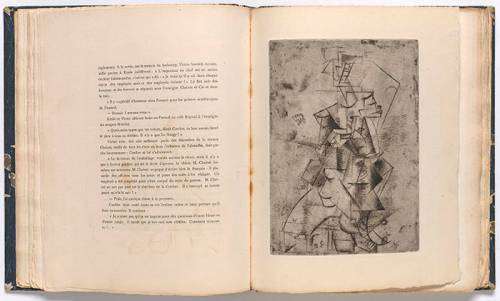

The Fractured Mirror

Picasso’s illustrations for Max Jacob’s poetic texts Saint Matorel and Le siège de Jérusalem are considered to be among his most important Cubist prints, created early in the history of the movement. One of Picasso’s first friends in Paris, the resolutely avant-garde Jacob, who was also a serious visual artist, was considered a “Cubist writer,” seeing his subject from multiple angles and in multiple states, much as the Cubists did visually.

Leave everything. Leave Dada. Leave your wife. Leave your mistress. Leave your hopes and fears. Leave your children in the woods. Leave the substance for the shadow. Leave your easy life, leave what you were given for the future. Set off on the roads.André Breton, Les pas perdus, 1924 (Translation by Mark Polizzotti)

Published the same year as his Surrealist Manifesto, in Les pas perdus Breton captured the insurgent, high-energy spirit of Surrealism in its earliest stages. “Those seeking a kind of cult pilgrimage to nowhere but the opposite of where one is,” writes critic and historian Mary Ann Caws, “would have found the ‘leave everything’ model alluring, even before—perhaps especially before—what one was leaving everything for had been clearly defined.”

L’achez tout! (Leave everything!)André Breton, Les pas perdus, 1924

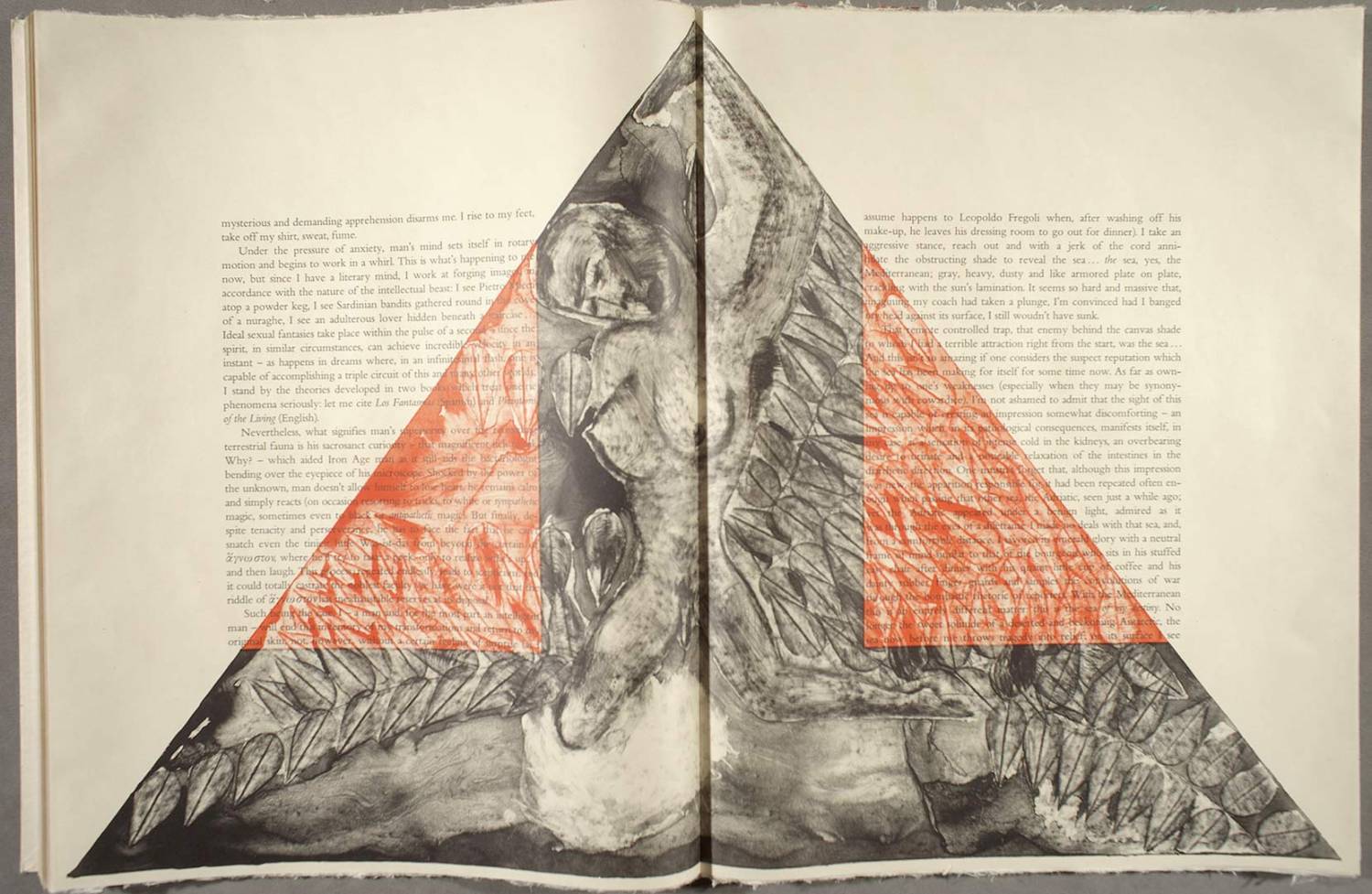

Paging through a great artist’s book is an art-viewing experience like no other. Each opening is a revelation of form, sequence, and meaning.

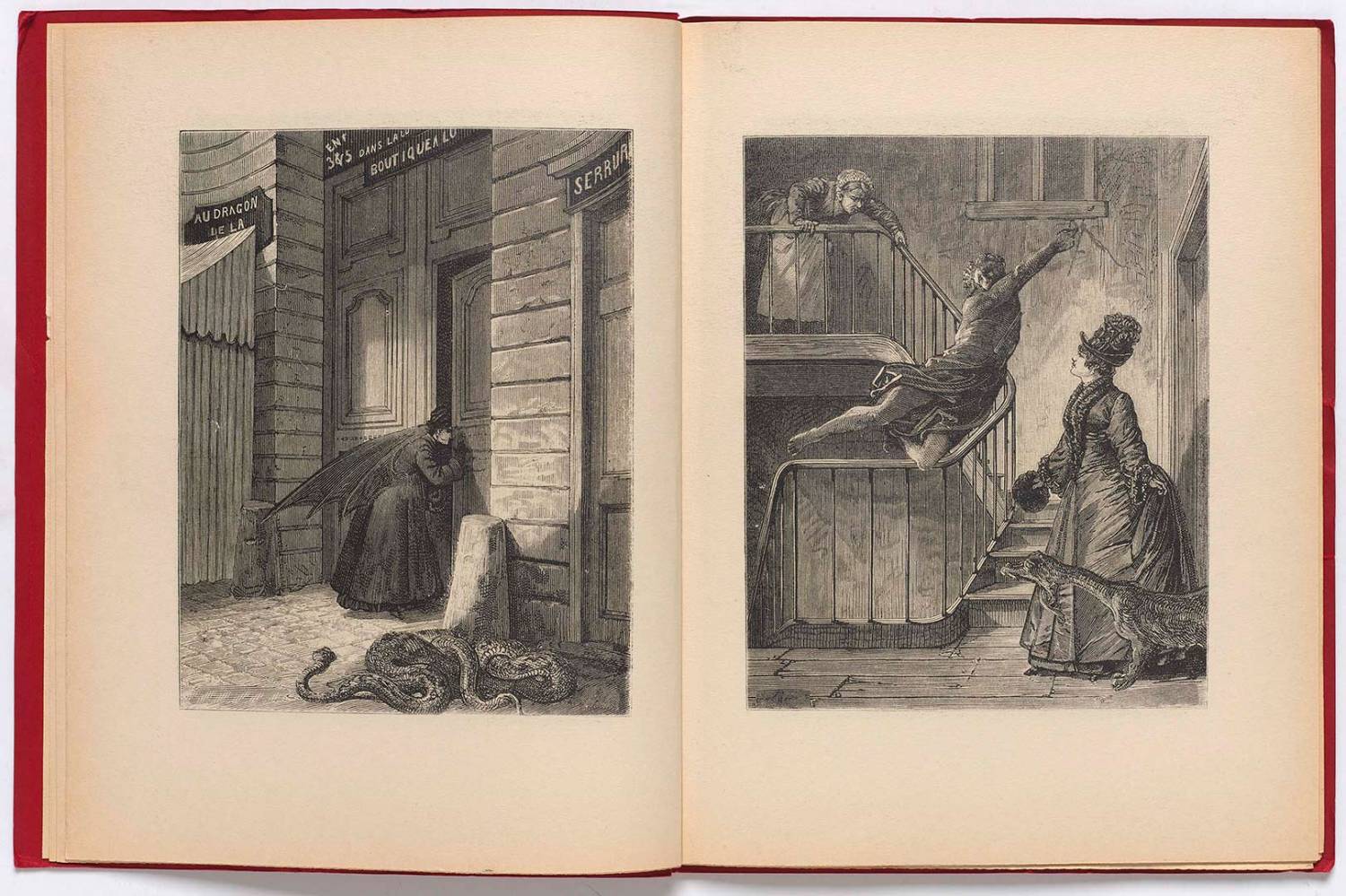

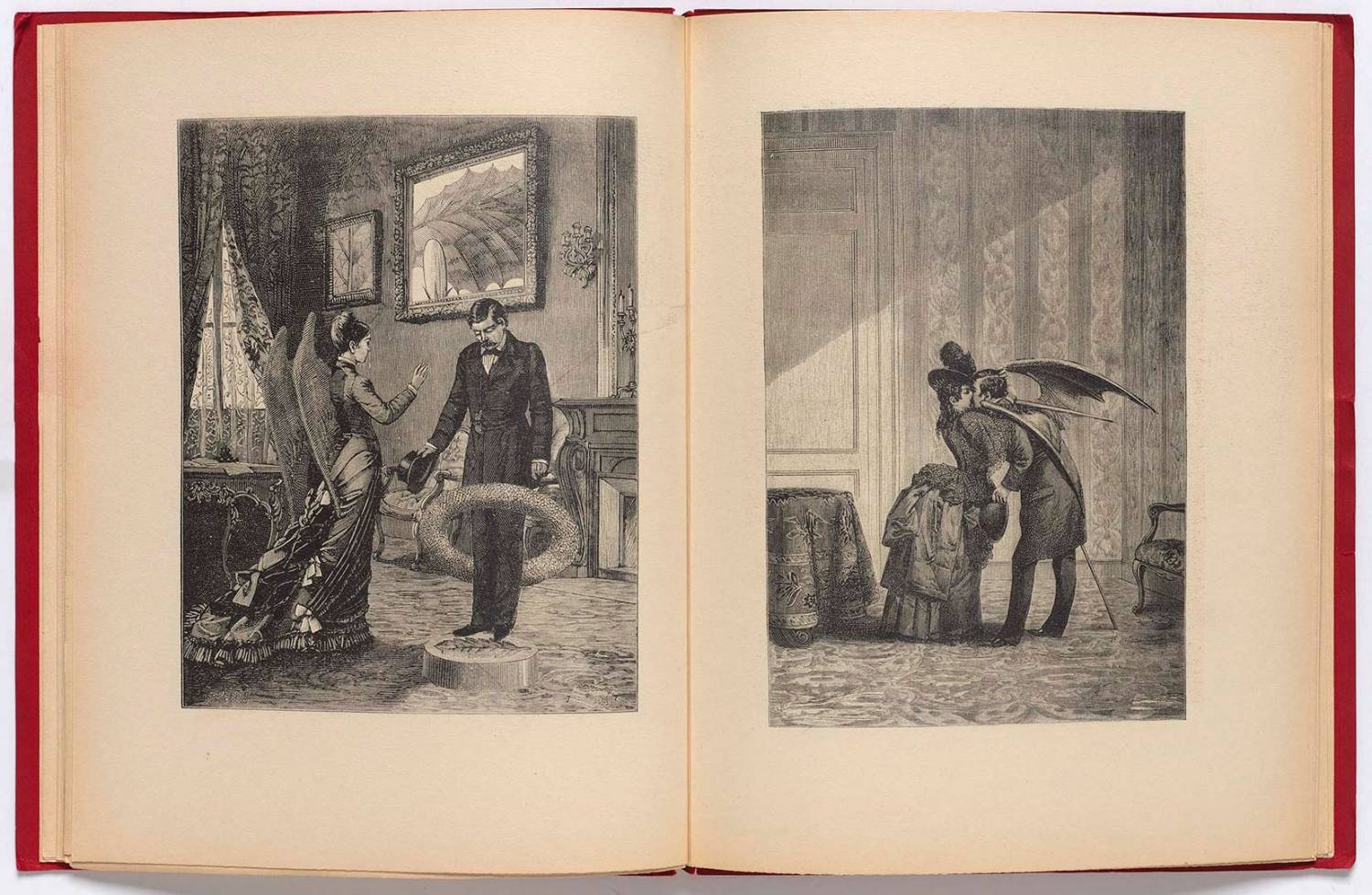

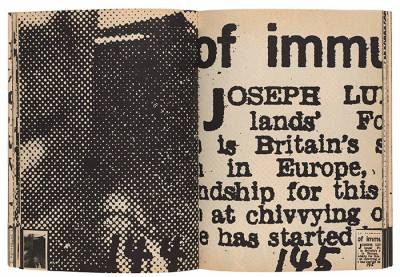

The experience of an artist’s book is intimate, tactile, and sequential. A gallery display can offer only a hint of that experience, but digital media can provide a partial solution by offering multiple page spreads, contextualizing material, and even representations of the entire contents of books online. Here is a sampling of pages from a few books in the Logan Collection.

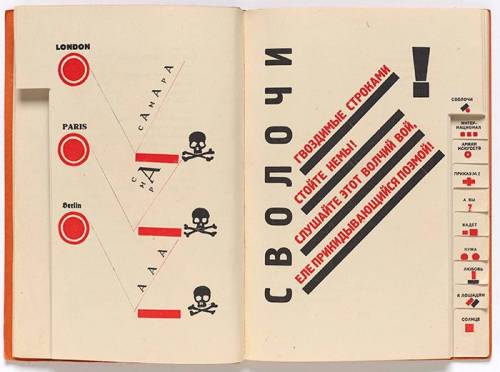

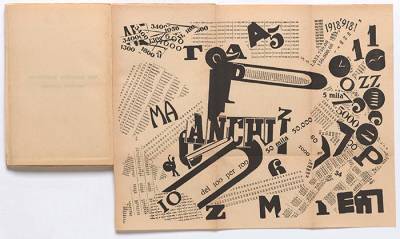

Designing a Revolution

Dlia Golosa is one of the great marriages of radical design and poetry. Designer El Lissitzky transformed Mayakovsky’s popular poems of revolution into typographic images, then created a book structure with tabbed icons so that any poem could be accessed directly.

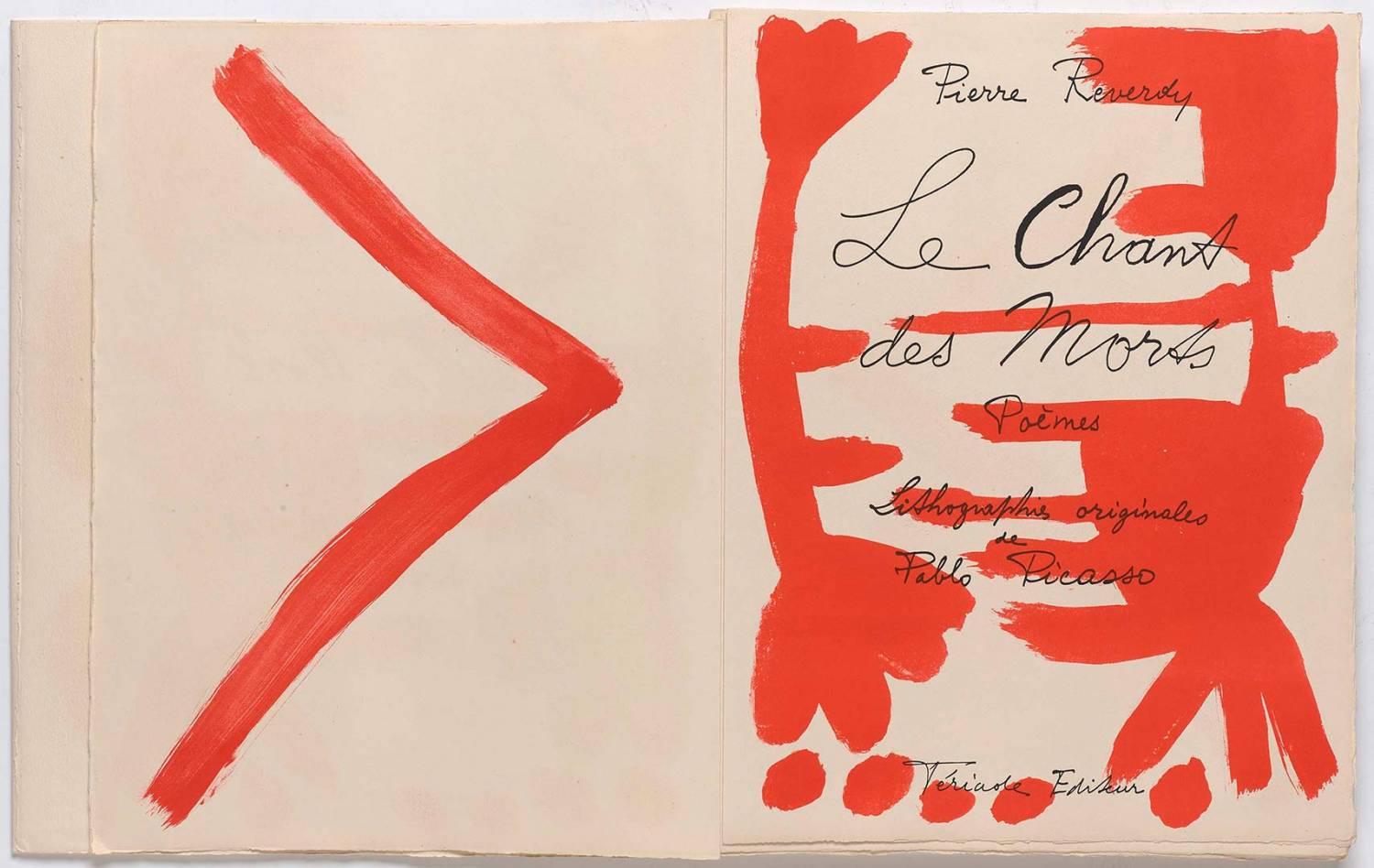

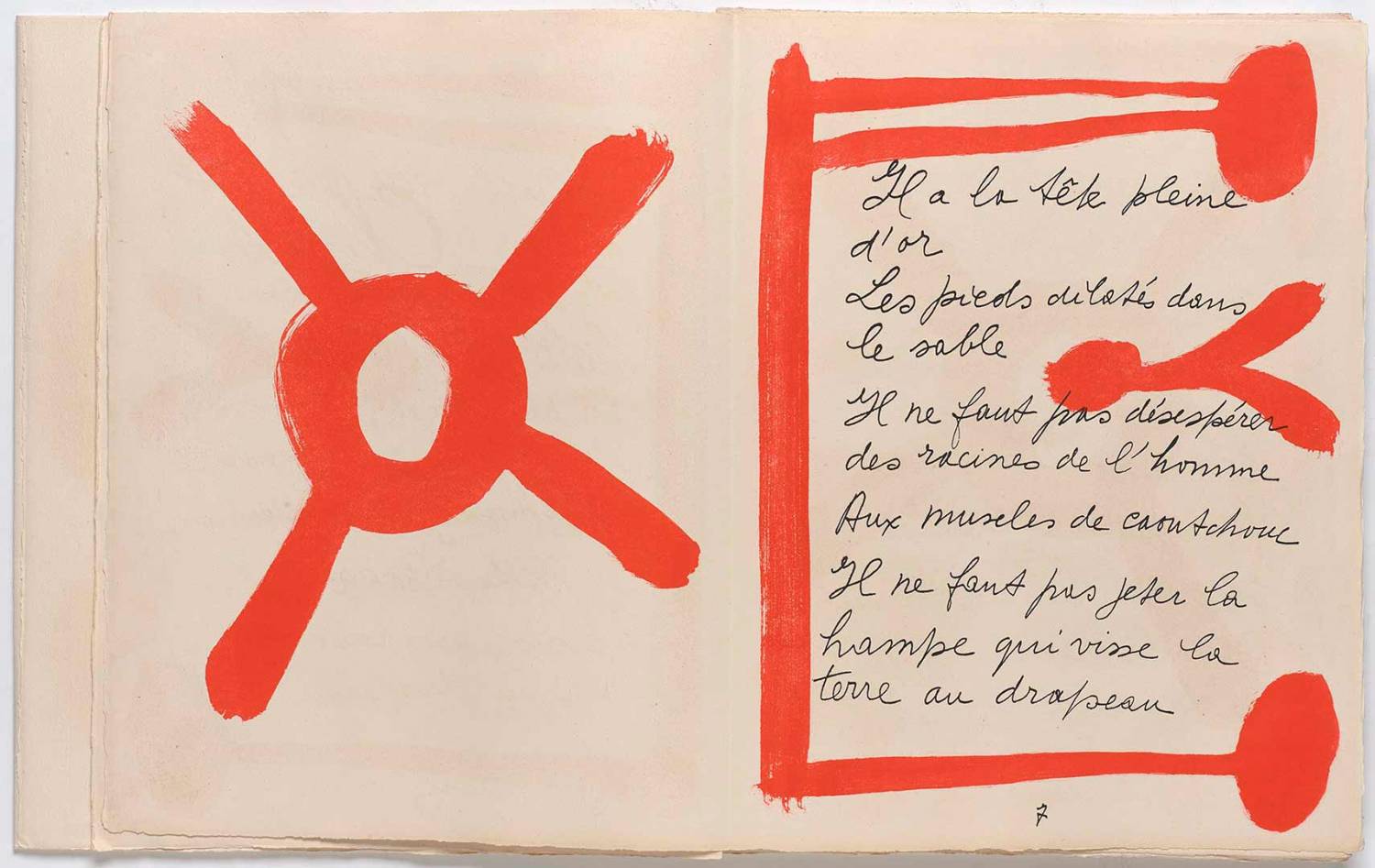

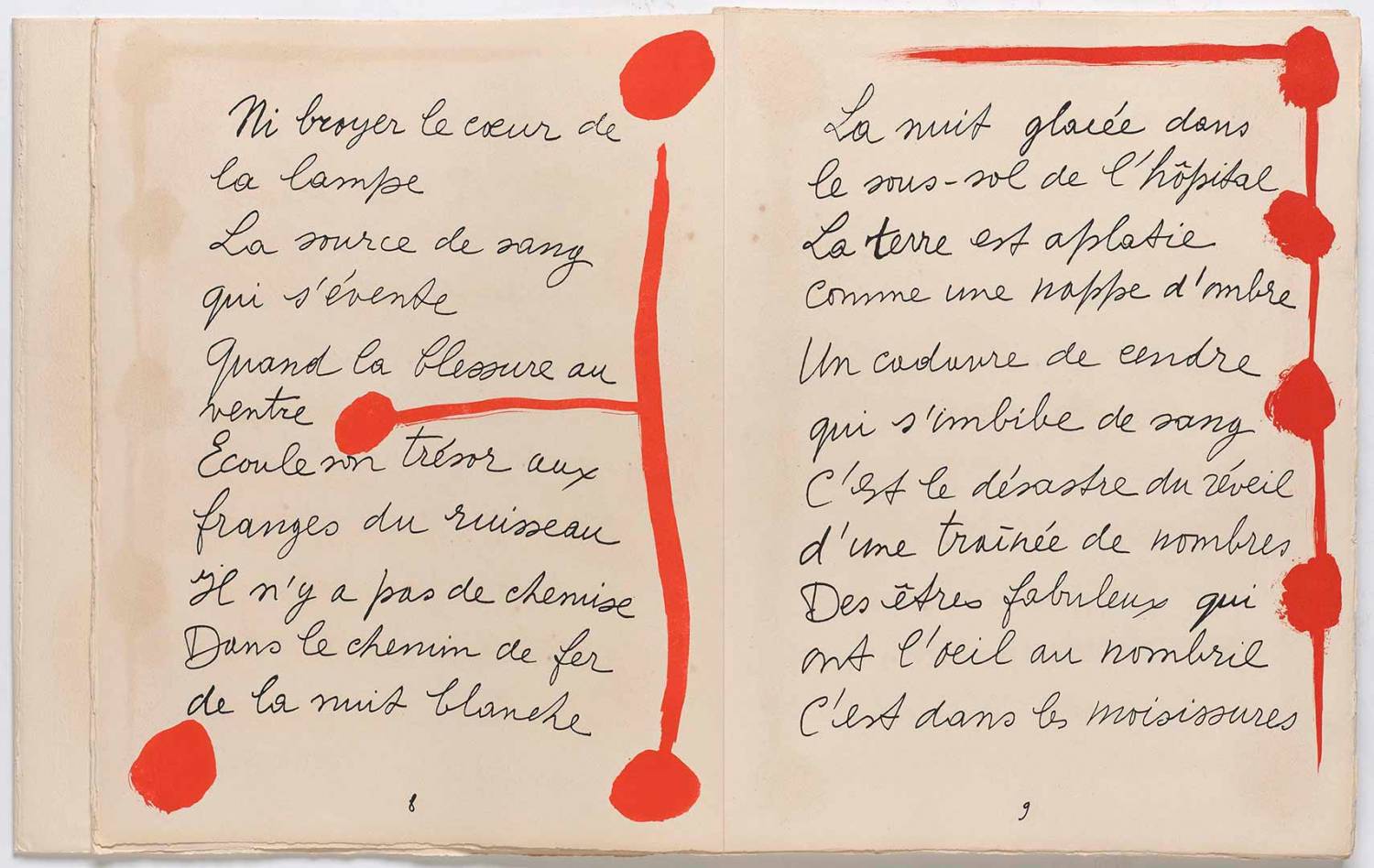

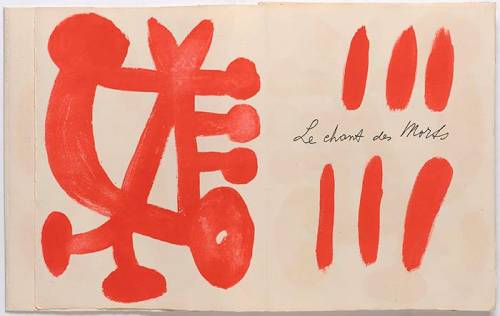

Postwar France: Illumination

Gertrude Stein once said that Picasso “had a certain way of writing his thoughts” in his art making, a remark particularly apt for his work in Le chant des morts. The bold forms cradle the handwritten poems of the poet Pierre Reverdy almost as in an illuminated manuscript.

Poetry goes to the heart by way of the eyes.Pierre Reverdy, Radio interview, 1950

Contemporary Artists’ Books

By the late twentieth century, the artist’s book had arrived in the mainstream. In the United States, artist’s book presses such as Gemini G. E. L. in Los Angeles, Universal Limited Art Editions in New York, and Arion Press in San Francisco were carrying forward the livre d’artiste tradition in editions with blue-chip artists. At the same time, community book arts centers emerged in New York, Minneapolis, Washington, and San Francisco to teach craft technique, and colleges and art schools began offering degrees in artist’s-book production.

In a time when, for many people, digital screens are replacing the traditional book for day-to-day reading, the artist’s book has become a kind of apotheosis of the book form, bringing reading into the realm of art—just as Vollard and Kahnweiler had intended back in Paris more than a century ago.

This Project

As the only works of art that must be handled to be fully experienced, artists’ books present a challenge for an institution charged with their conservation and display. The current project addresses this challenge by making contents of, and related information about, selected books from the collection available online using the capabilities of digital media. The project aims to raise the accessibility of the collection and create greater public understanding and awareness of what critic and historian Johanna Drucker has called “the quintessential twentieth-century art form.” This project intends to make significant works by many of the most important artists of the century available for public access in their entirety for the first time.

Major support for this project comes from:

The Jonathan Logan Family Foundation

The Reva and David Logan Foundation

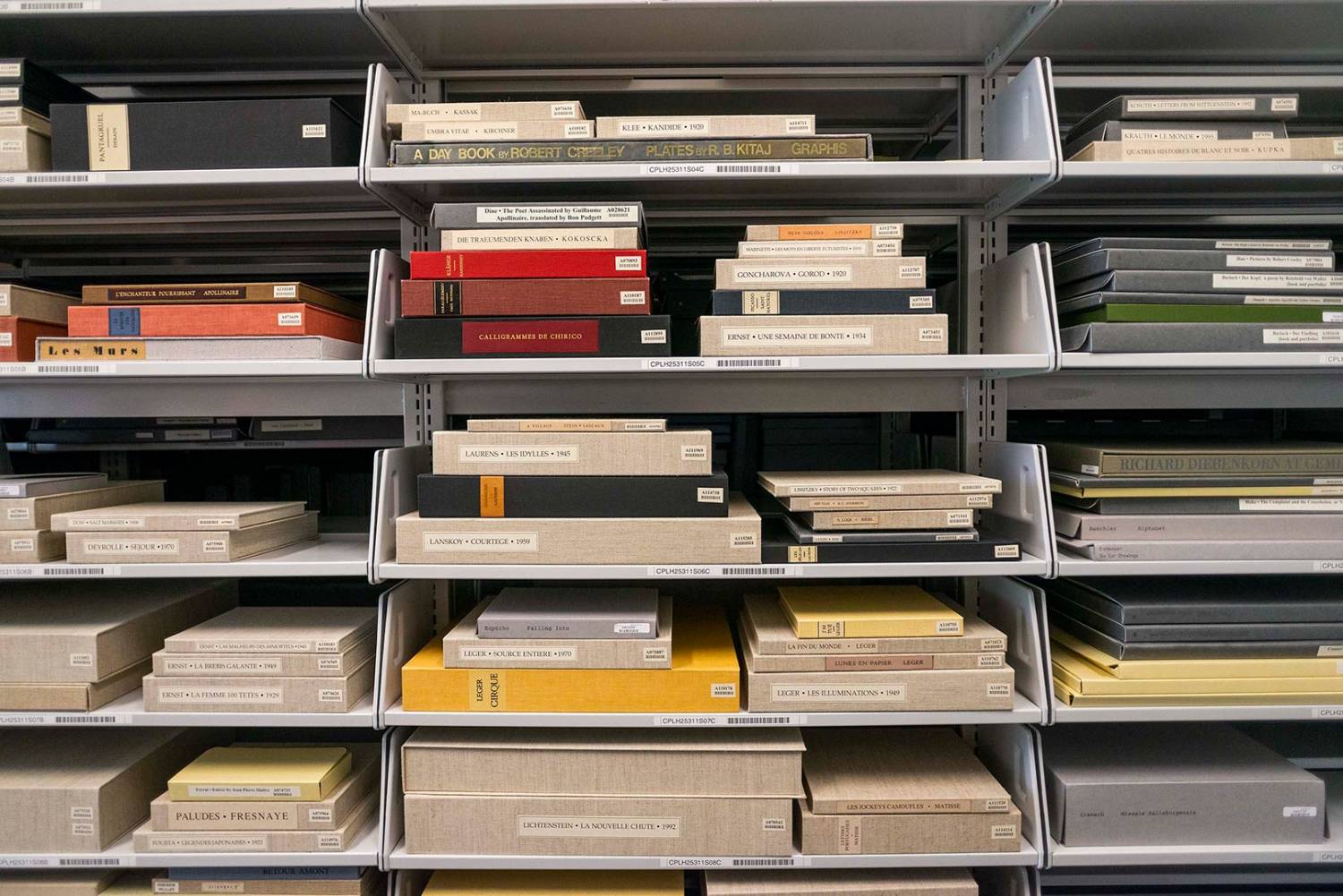

The Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books

Over a period of twenty years, the Chicago collectors Reva and David Logan built one of the great private collections of artists’ books, and in 1998 donated that collection to the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, home of works on paper at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

With more than 400 carefully assembled titles, the Logan Collection contains many of the most important works in the genre, with significant artists’ books representing virtually every major art movement dating from the beginnings of the livre d’artiste in the late nineteenth century. Augmented by important works already held by the Achenbach Foundation, the Logan gift established the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco as stewards of one of the most historically significant collections of artists’ books in the United States.